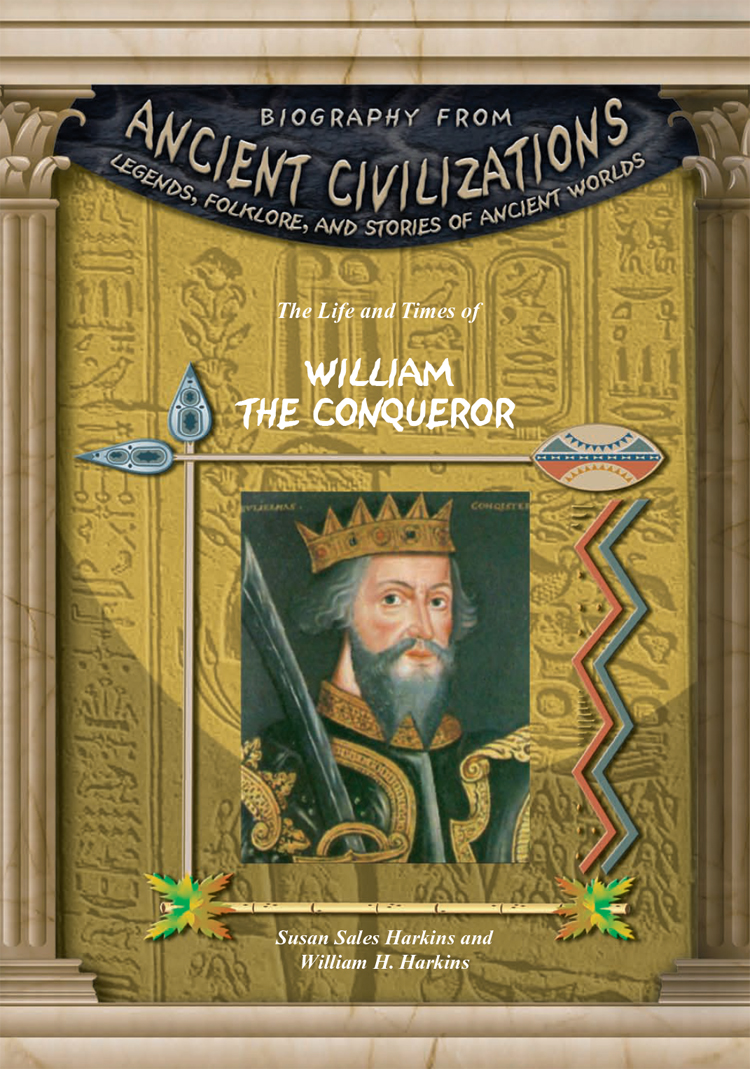

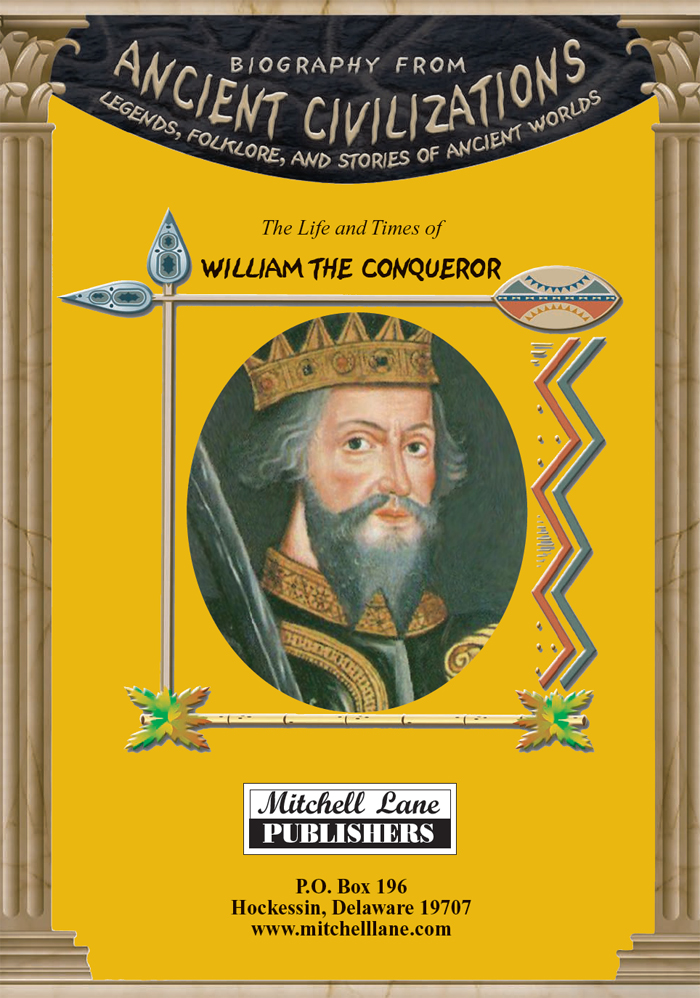

The Life and Times of:

Alexander the Great

Archimedes

Aristotle

Augustus Caesar

Buddha

Catherine the Great

Charlemagne

Cicero

Cleopatra

Confucius

Constantine

Erik the Red

Genghis Khan

Hammurabi

Herodotus

Hippocrates

Homer

Joan of Arc

Julius Caesar

King Arthur

Leif Eriksson

Marco Polo

Moses

Nero

Nostradamus

Pericles

Plato

Pythagoras

Rameses the Great

Richard the Lionheart

Socrates

Thucydides

William the Conqueror

Mitchell LanePUBLISHERS

Copyright 2009 by Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Printing 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harkins, Susan Sales.

The life and times of William the Conqueror / by Susan Sales Harkins and William H. Harkins.

p. cm. (Biography from ancient civilizations)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-58415-700-7 (library bound)

1. William I, King of England, 1027 or 81087Juvenile literature. 2. Great BritainHistoryWilliam I, 10661087Juvenile literature. 3. Great BritainKings and rulersBiographyJuvenile literature. 4. NobilityFranceNormandyBiographyJuvenile literature. 5. NormansGreat BritainBiographyJuvenile literature. I. Harkins, William H. II. Title.

DA197.H37 2008

942.021092dc22

[B]

2008020924

eISBN: 978-1-5457-4853-4

ABOUT THE AUTHORS: Susan and William Harkins live in Kentucky, where they enjoy writing together for children. Susan has written many books for adults and children. William is a history buff. In addition to writing, he is a member of the Air National Guard.

PUBLISHERS NOTE: This story is based on the authors extensive research, which they believe to be accurate. Documentation of such research is contained on page 46.

The internet sites referenced herein were active as of the publication date. Due to the fleeting nature of some web sites, we cannot guarantee they will all be active when you are reading this book.

To reflect current usage, we have chosen to use the secular era designations BCE (before the common era) and CE (of the common era) instead of the traditional designations BC (before Christ) and AD (anno Domini, in the year of the Lord).

PLB

CONTENTS

*For Your Information

INVASION!

On a late September morning in 1066, English peasants living near the southern coast turned from their tasks in fear. The deep blast of a Viking horn rumbled through every field and village. They knew the horn meant certain death to anyone caught by the invader, William, the Duke of Normandy. Many would choose death rather than serve the tyrant from across the channel who claimed the English throne as his own.

Frantic peasants hid in the nearby woods and watched the huge invasion fleet sail into the still water of Pevensey Bay. William was watching too, from the deck of his ship, Mora. One by one, his small boats landed, unopposed.

With no one to stop them, the invaders made themselves at home. First they took down the masts and sails of the ships and led their horses ashore. They used the masts and sails to build temporary forts. Knights rode out on a short scouting mission. Cooks lit fires and assembled roasting spits. William and his staff sat at a crescent-shaped table, while seaman unloaded provisions, and armorers, masons, and smiths set up makeshift shops.

From behind a hill, an English knight watched. Mounting his fastest horse, he rode toward London and King Harold. Soon, huge beacon fires were signaling the alarm throughout the southern villagesNormans were in England!

Meanwhile, news of the southern invasion reached Harold. He had just secured an overwhelming victory over the king of Norway at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire, but there was no time to celebrate. Immediately, he and his royal forces, the housecarls, began a hard march south. He had to reach London before William! (Historians dont know when Harold learned of Williams landing. According to the Norman poet Wace, Harold heard the news before leaving Yorkshire.)

Soon, Robert Fitz Wymarc, an English landowner who claimed to be related to William, showed up at the Norman camp. He warned William to go home. Harold had just slaughtered over twenty thousand Norwegians in northern England and was marching south with a huge army. Defiant and confident, William boasted that he had sixty thousand men, but could defeat Harold with only ten thousand (which is closer to what he really had).

At that time, England had no professional army. Only the housecarls, the kings household troops, were a consistent force. The king depended upon his lords to provide soldiers. While Harold marched south to London, forces in the south gathered and waited. Harold summoned the northern earls Edwin and Morcar to join his forces in London.

The archers of Englands King Harold overwhelmed King Harold of Norway, killing him with an arrow at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. The English king would march from there to his destiny at Hastings.

Men flowed into London from southern and eastern England. Edwin and Morcar never made it to London or the subsequent battle. Considering that their earldoms covered almost half of England, their absence was significant.

In Hastings, a monk spoke on Harolds behalf, asking William to return to Normandy. He acknowledged Williams claim to the throne. However, King Edward, before he died, named Harold, the Earl of Wessex, his heir. Harold was the rightful king of England regardless of what the old king might have promised William years ago. William challenged Harold to single combat, which Harold angrily refused.

Two weeks after William landed, Harold marched his army south down the great road from London to Hastings. They stopped where the road left the forest and sloped downward. (At the time of the battle, the area had no name. Later it was named Senlac Hill.) Harold was still several miles from the Normans seaside camp.

That night, October 13, Harold camped and chose a good spot for battle. From the crest of the hill, he could see an advancing army. At the base of the hill, his men dug a deep ditch. His foot soldiers carried javelins and a two-handed battle-ax, which could split a head and kill a horse with a single blow. Men from the countryside carried farm tools. None of them wore armor.

Later that night, the English camp rang with song as the men drank instead of resting. In the Norman camp, Williams half brother, Bishop Odo, led the men in prayer.

By 9:00 A.M. on October 14, 1066, Harold could see the Normans approaching from his hilltop camp. His men formed a semicircular wall of overlapped shields nearly half a mile long, with the strongest of his troops in the middle. They covered the slope of the hill that the Normans would have to climb. At the summit, Harold stood under his standard, a golden banner with the outline of a fighting man.

Next page