About the Authors:

David Musgrove is Content Director for BBC History Magazine, BBC World Histories and BBC History Revealed magazines, and the website www.historyextra.com . He is the author of 100 Places That Made Britain, and he has a PhD in medieval archaeology.

Michael Lewis is Head of Portable Antiquities & Treasure at the British Museum and Visiting Professor in Archaeology at the University of Reading. An expert on the Bayeux Tapestry, he is the author of The Real World of the Bayeux Tapestry. He is also a member of the Bayeux Tapestry scientific committee that is advising Bayeux Museum on the reinterpretation and redisplay of the embroidery.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Digging up Britain: Ten Discoveries, a Million Years of History

Mike Pitts

The Land of the White Horse: Visions of England

David Miles

Medieval People: Vivid Lives in a Distant Landscape

Michael Prestwich

Be the first to know about our new releases, exclusive content and author events by visiting

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

CONTENTS

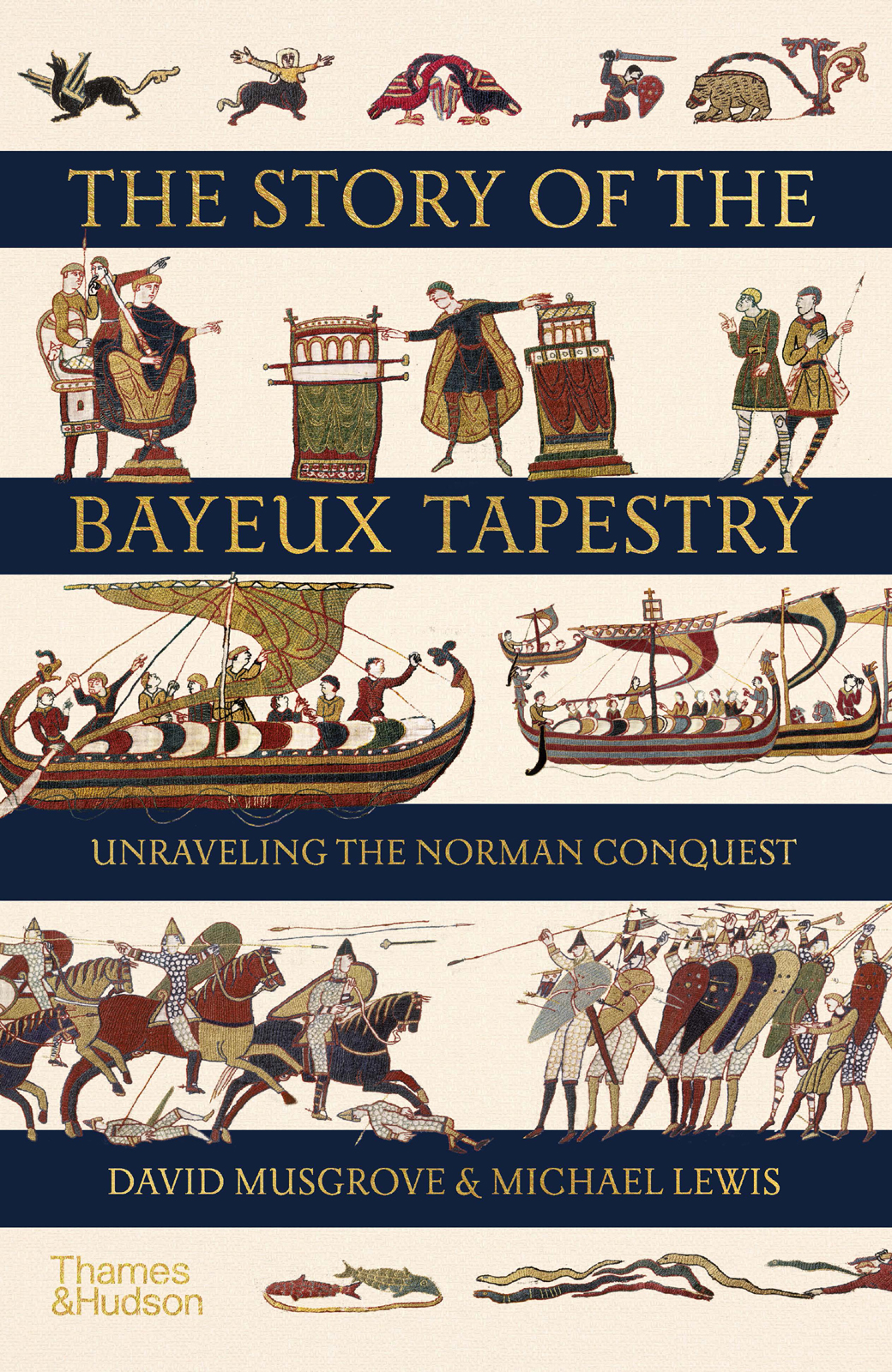

Political intrigue, extreme violence, graphic nudity the Bayeux Tapestry has it all. Most people probably know that it shows the stricken Anglo-Saxon king Harold II (Godwinson) dying on the battlefield of Hastings in 1066 amid a shower of arrows, while the mounted knights of Duke William of Normandy mow down his closest followers. Axes clash against helmets, swords slash and spears fly, fallen warriors are trampled beneath charging hooves and have their armour stripped from them, leaving their naked bodies lying on the ground. All this is shown on a strip of linen around 68 m (223 ft) long, with an intensity and gory vividness that still has great power and immediacy today, nearly 1,000 years after the Tapestry was created.

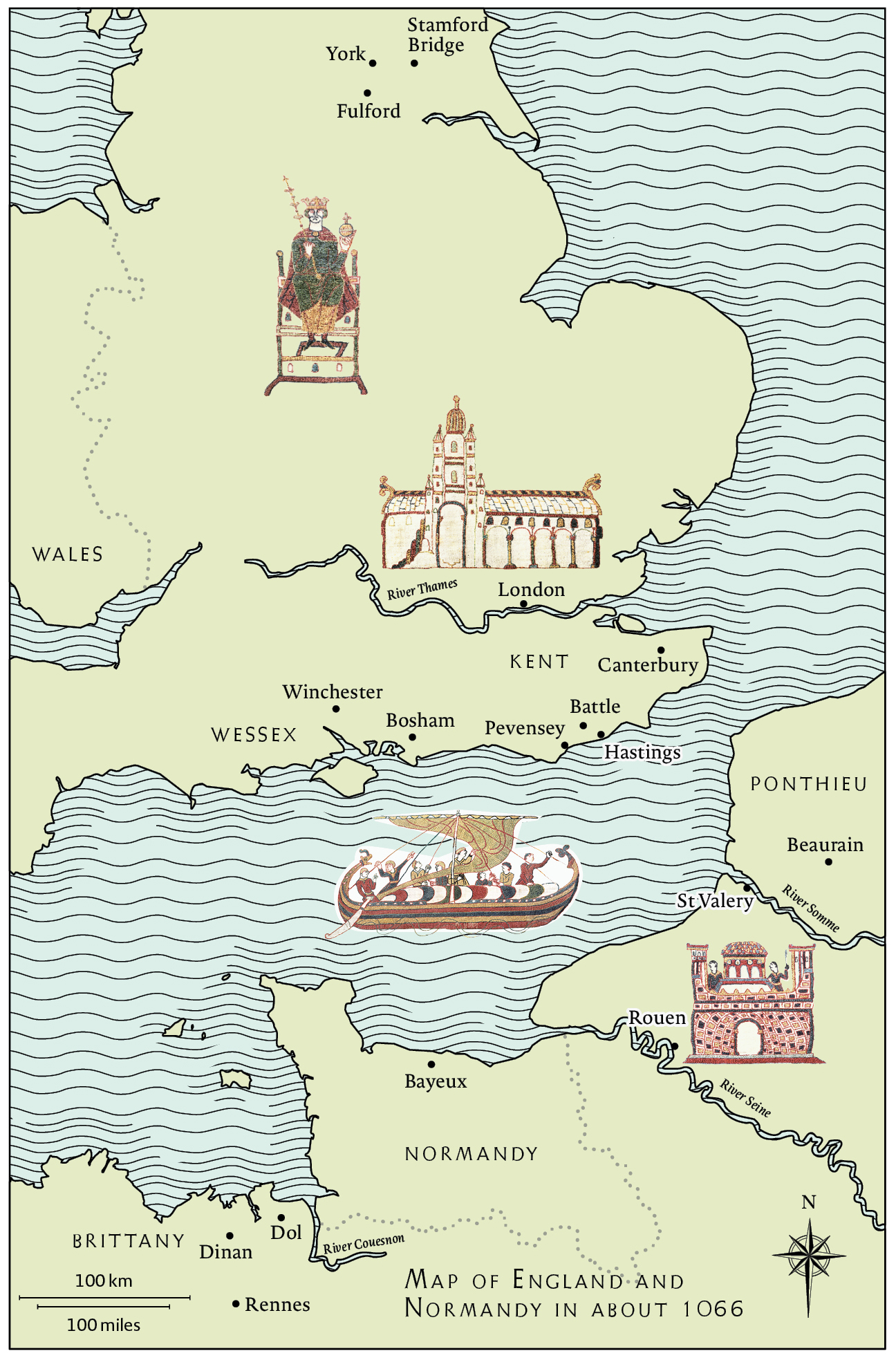

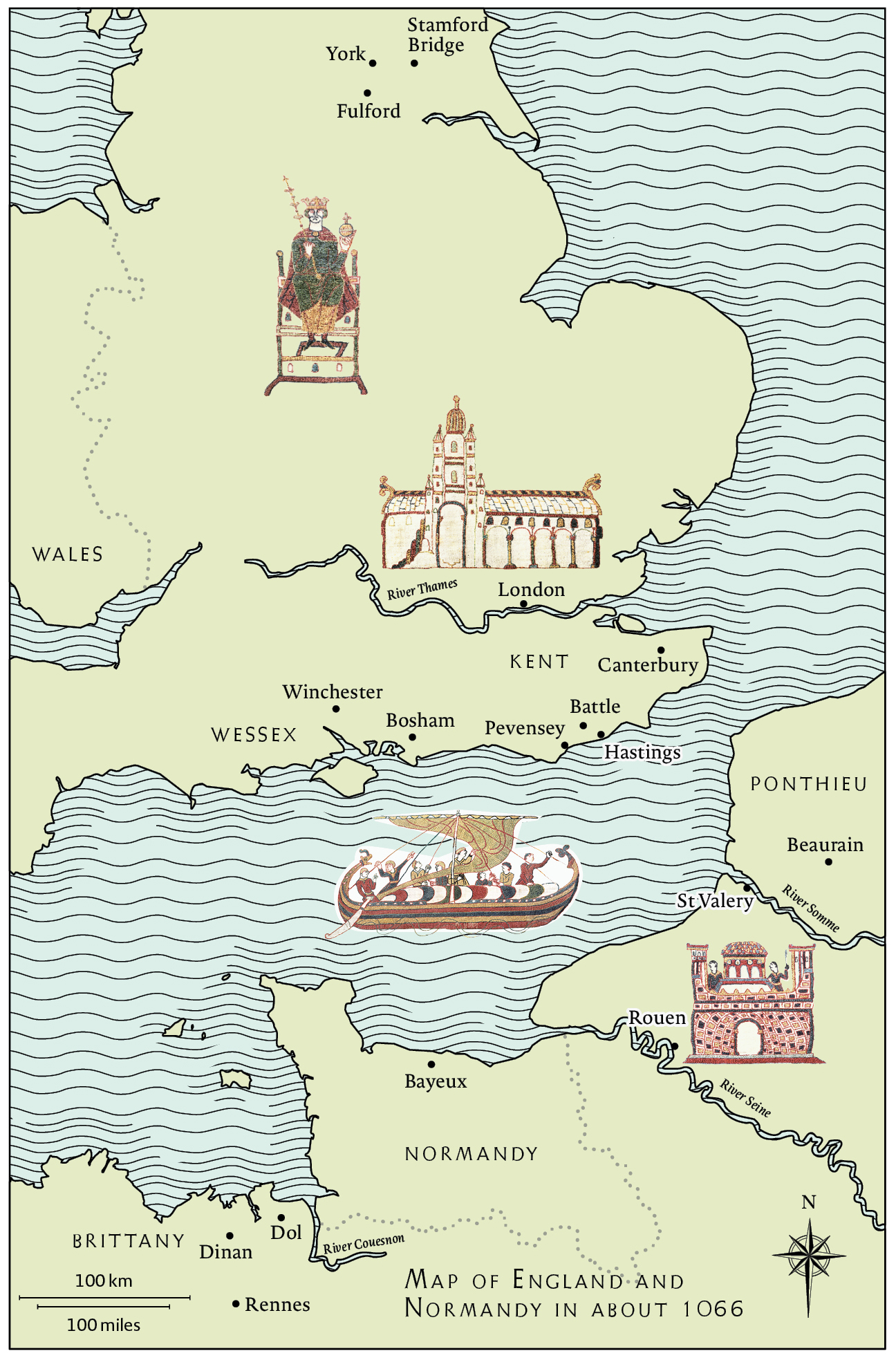

At the time of the Norman Conquest, England was a relatively new, but wealthy, kingdom, and Normandy found itself in a position of strength.

The scene of high drama is the climactic moment of this most famous of battles, providing the breakthrough William needed to conquer England and forever change British history. Leading up to this final bloody act, the Tapestry shows the full fury of the Battle of Hastings, from the first manoeuvres and troop deployments, through the Norman cavalry assault on the shield-wall of the Anglo-Saxons, as they sturdily defended their hilltop position despite the death of Harolds brothers and then the tactical success of the Norman archers coming into play to weaken English resolve and finally allow the invading horsemen to gain the upper hand.

So, on the surface at least, the Bayeux Tapestry tells the dramatic tale of how the last Anglo-Saxon king of England was killed in battle and was replaced on the throne by his Norman adversary. However, there is much more to this remarkable historical and artistic treasure than that. While the battle itself may be the most familiar and famous episode depicted, the Tapestry devotes much more space almost three quarters of its length to the run-up to this clash. Before it gets anywhere near the battlefield, it charts the political machinations on both sides of the Channel in the years leading up to the Conquest, introducing key characters in the story and showing the moments that led to Duke Williams decision to launch his assault to claim the English crown.

The story of 1066 has been drummed into British schoolchildren for generations in part because it is such a dramatic tale, but no doubt also because it has such a fantastic artistic accompaniment in the form of the Bayeux Tapestry. The fact that the embroidery tells the story through images more than words, apart from the terse captions, lends it an air of approachability that a standard medieval documentary source, typically written in Latin in challenging handwriting, simply cannot match. Most of all, perhaps, it is famous because 1066 was undeniably a turning point in British history. The remarkable achievement of Duke William over the English is noted also in France, although it perhaps does not have such a hold on the public imagination there as the history of the French monarchy. Whereas for the English 1066 is a key moment that marks the end of Anglo-Saxon England, for the French the major historical year of note is 1789 the beginning of the French Revolution. But both the English and French recognize that the Conquest also bound together the history of the two countries in a profound way, perhaps never again to be repeated until the two world wars of the twentieth century, and specifically the liberation of Normandy by the Allies in 1944. Even though the Conquest was of England (not Britain) and was by Normans (not the French), it had major long-term repercussions for the rest of Britain and Ireland too. The different ways in which the British and French, or more specifically the English and the Normans, have responded to the story of the Conquest have influenced how the Bayeux Tapestry is appreciated and understood.

Dispelling some myths

The first thing that should be said in any book about the Bayeux Tapestry is that it is not a tapestry at all and it probably wasnt made in Bayeux. Leaving aside for now the question of where it was produced, the Bayeux Tapestry should in fact more accurately be described as an embroidery, where a design is stitched on to fabric in this case on linen using woollen threads rather than a tapestry.

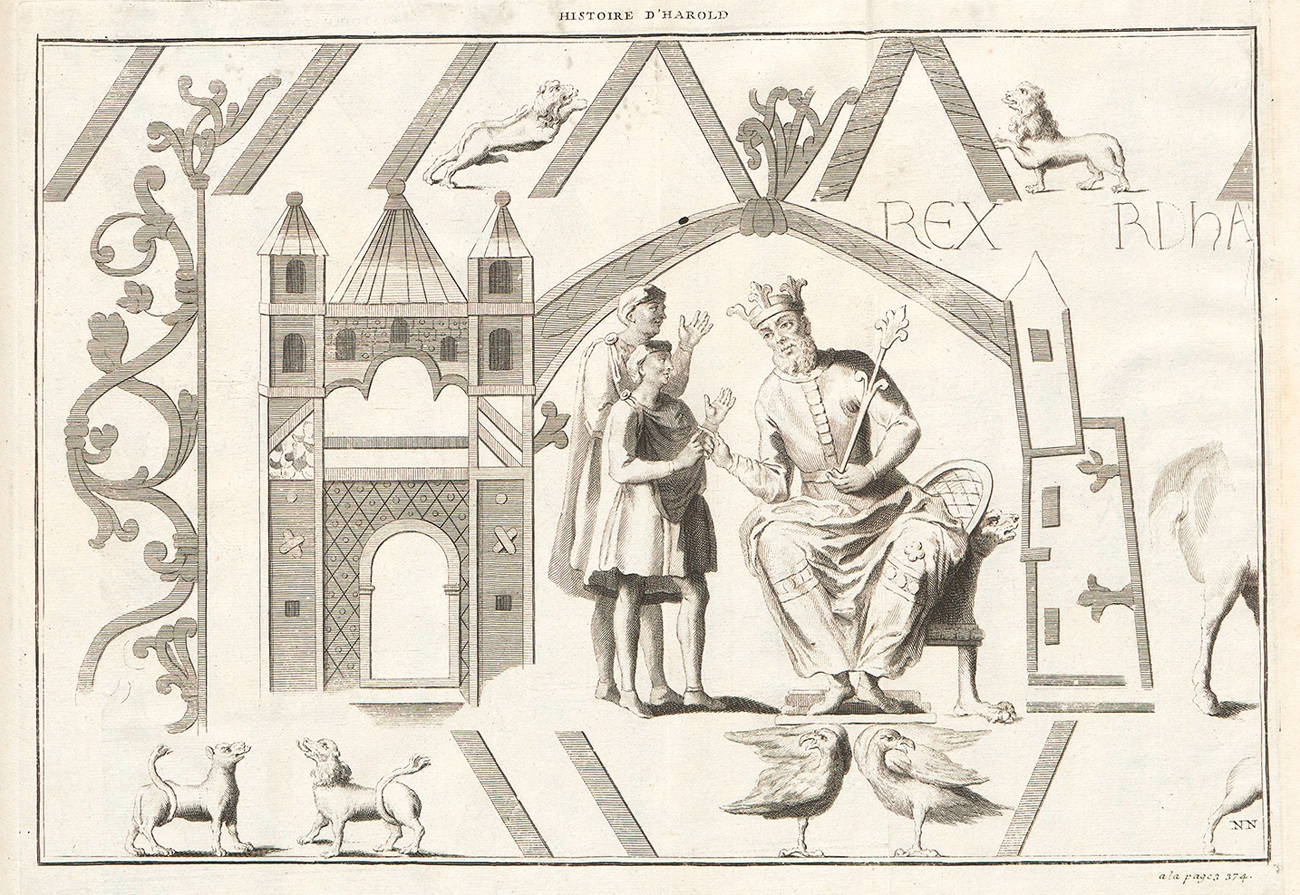

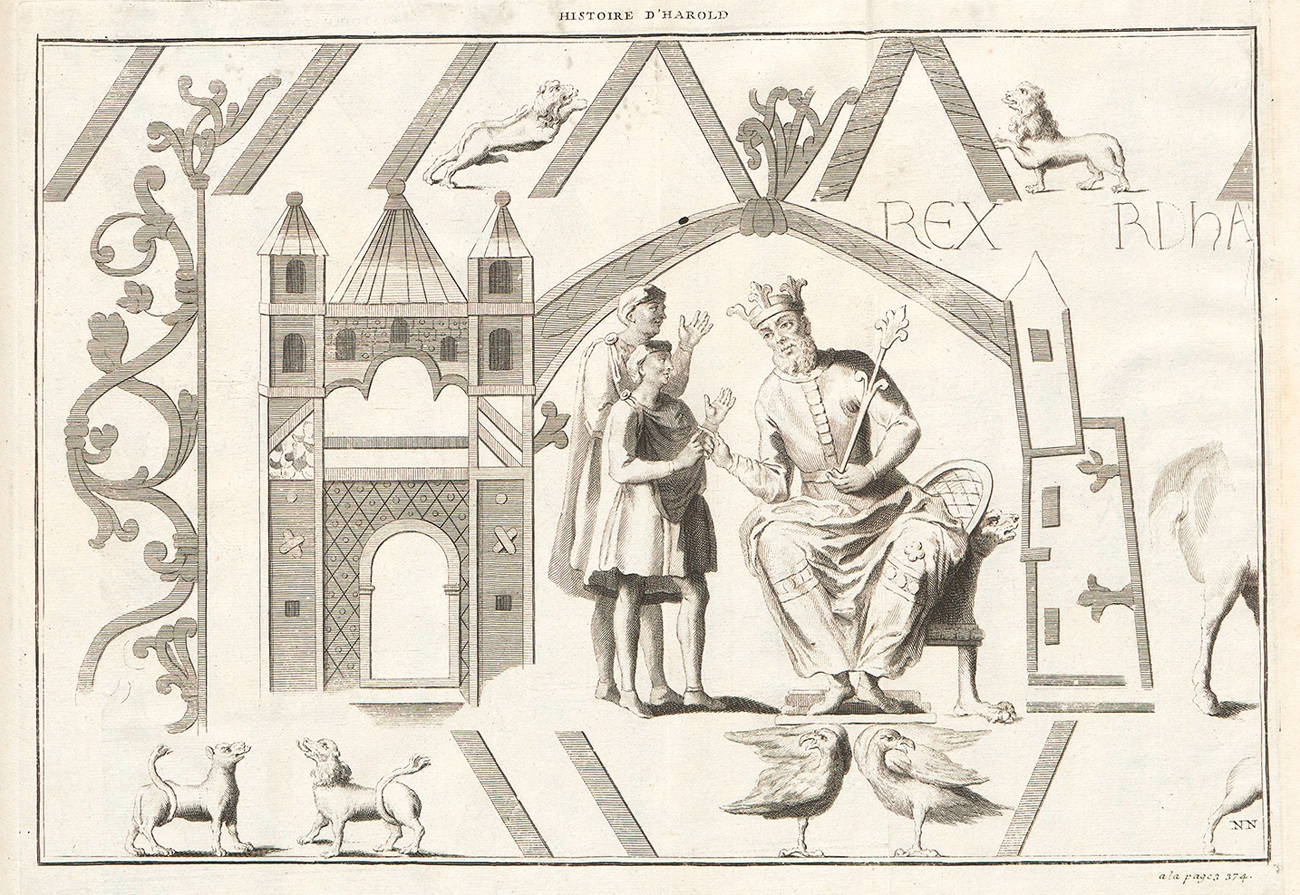

The earliest known drawing of the first scene of the Bayeux Tapestry (dating to before 1721), from the collection of papers of Nicolas-Joseph Foucault. It was this drawing that motivated Bernard de Montfaucon to seek out the Bayeux Tapestry, though he was unsure exactly what he was looking for.

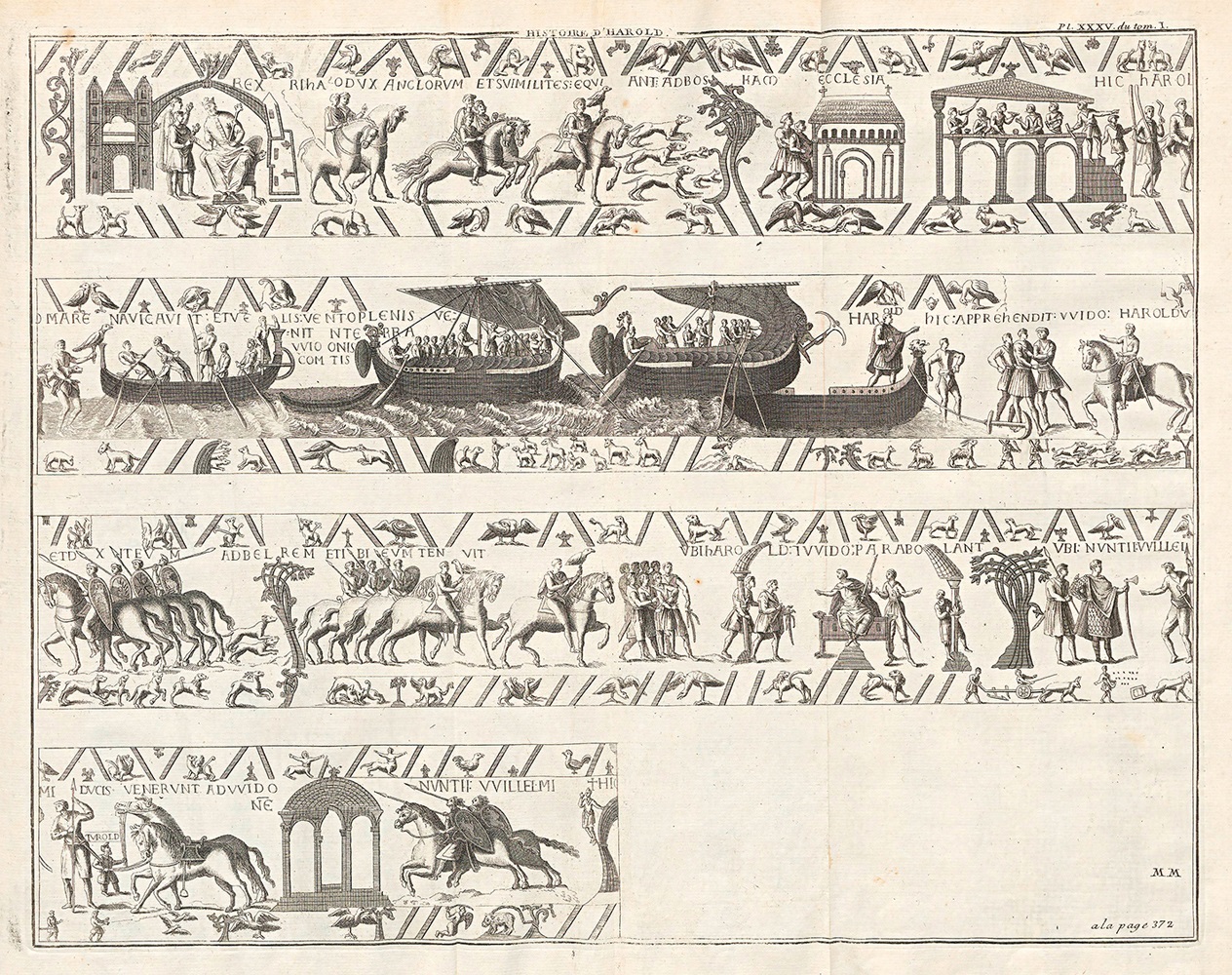

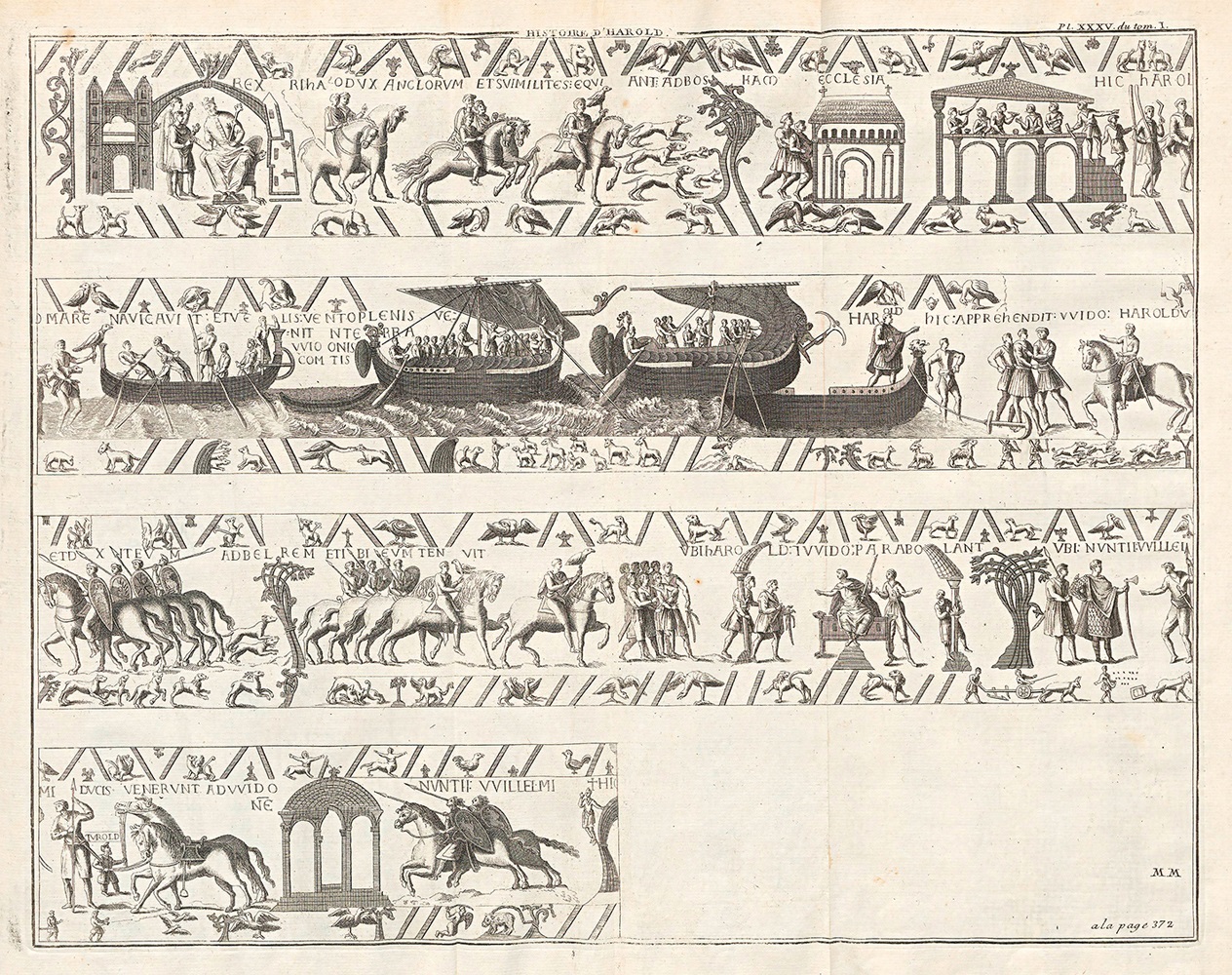

The same scene of the Bayeux Tapestry as published by Bernard de Montfaucon in 1729. Montfaucon was primarily interested in the embroidery because it related to the history of the French monarchy.

In the first volume (dated 1729) of his work on historical monuments associated with the French monarchy, Bernard de Montfaucon included this engraving of the first part (up to Scene 11) of the Bayeux Tapestry, with the figures rather artistically portrayed.

The confusion dates back to 1729, when a French monk and antiquarian, Bernard de Montfaucon, published engravings made from a drawing of part of the Bayeux Tapestry in the first volume of a substantial work he produced on the historical monuments associated with the French monarchy. The original drawing had been made some years earlier and came from the collection of another Frenchman, Nicolas-Joseph Foucault, along with a detailed description. In his account, Montfaucon used the word

Next page