R. Howard Bloch - A Needle in the Right Hand of God: The Norman Conquest of 1066 and the Making and Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry

Here you can read online R. Howard Bloch - A Needle in the Right Hand of God: The Norman Conquest of 1066 and the Making and Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2006, publisher: Random House, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Needle in the Right Hand of God: The Norman Conquest of 1066 and the Making and Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

A Needle in the Right Hand of God: The Norman Conquest of 1066 and the Making and Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Needle in the Right Hand of God: The Norman Conquest of 1066 and the Making and Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

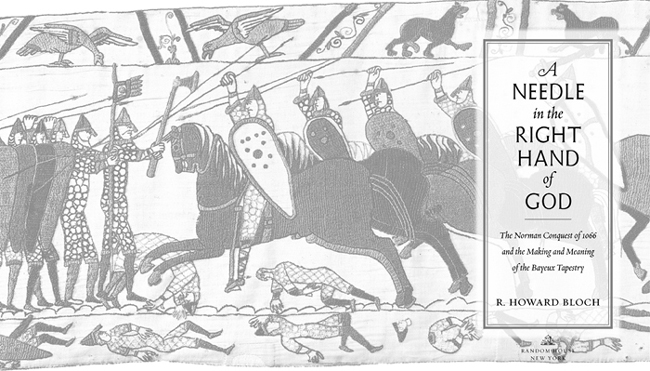

Bloch opens with a gripping account of the event that inspired the Tapestry: the swift, bloody Battle of Hastings, in which the Norman bastard William defeated the Anglo-Saxon king, Harold, and laid claim to England under his new title, William the Conqueror. But to truly understand the connection between battle and embroidery, one must retrace the web of international intrigue and scandal that climaxed at Hastings. Bloch demonstrates how, with astonishing intimacy and immediacy, the artisans who fashioned this work of textile art brought to life a moment that changed the course of British culture and history.

Every age has cherished the Tapestry for different reasons and read new meaning into its enigmatic words and images. French nationalists in the mid-nineteenth century, fired by Tapestrys evocation of military glory, unearthed the lost French epic The Song of Roland, which Norman troops sang as they marched to victory in 1066. As the Nazis tightened their grip on Europe, Hitler

sent a team to France to study the Tapestry, decode its Nordic elements, and, at the end of the war, with Paris under siege, bring the precious cloth to Berlin. The richest horde of buried Anglo-Saxon treasure, the matchless beauty of Byzantine silk, Aesops strange fable The Swallow and the Linseed, the colony that Anglo-Saxon nobles founded in the Middle East following their defeat at Hastingsall are brilliantly woven into Blochs riveting narrative.

Seamlessly integrating Norman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Byzantine elements, the Bayeux Tapestry ranks with Chartres and the Tower of London as a crowning achievement of medieval Europe. And yet, more than a work of art, the Tapestry served as the suture that bound up the wounds of 1066.

Enhanced by a stunning full-color insert that includes reproductions of the complete Tapestry, A Needle in the Right Hand of God will stand with The Professor and the Madman and How the Irish Saved Civilization as a triumph of popular history.

R. Howard Bloch: author's other books

Who wrote A Needle in the Right Hand of God: The Norman Conquest of 1066 and the Making and Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.