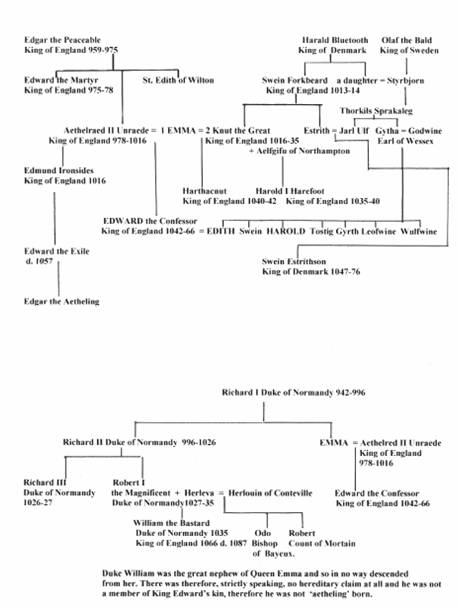

Top : Anglo-Danish dynasties of the eleventh century.

Bottom : William of Normandy and the English throne.

Even after well over a thousand years since it was accomplished, the Norman Conquest of England still holds a peculiar fascination for many people. There had been other invasions and successful conquests of this country from the Roman invasion in the reign of the Emperor Claudius and the advent of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes in the fifth century to the Viking invasions of the ninth and, early in the eleventh century, the conquest by Cnut the Great and his Danes. But the invasion by Duke William, the bastard of Normandy, was, in many respects, qualitatively different.

Cnut the Great had imposed his rule on the country and inserted many of his higher ranking supporters into positions of power and influence, allowing the rank and file of his armies to acquire lands left vacant after the battles between the English and the Danes. But he had not, for the most part, supplanted the native English nobility or carried out a massive transfer of land and power. Indeed, two of his highest ranking nobles were Englishmen raised to the rank of Earl and given the status and power of provincial governors; Earl Leofric in Mercia, the son of an English Ealdorman and Godwine, the thegn of Sussex, in Wessex.

But Duke William did not only make himself King, as others had done before him, nor did he merely add yet another cohort of nobles to the ranks of those already in power, instead he virtually eliminated the whole of the existing governing class and transferred the ownership of their estates to his own somewhat mixed collection of followers, Bretons, Flemings, Poitevins and, above all, Normans.

This book is an attempt to convey the manner in which this invasion and conquest was devised, planned and executed. It describes the steps taken to establish, in the eyes of other European princes and of the Papacy, Duke Williams right to the English throne, by asserting an hereditary claim to the throne, as a relative of the saintly, recently deceased, King Edward, who was alleged to have actually designated the Duke as his heir, and by manoeuvring the Kings successor, Harold II, the former Earl of Wessex, recognized even by the Normans themselves as the Dux Anglorum (Duke of the English), just as William himself was Dux Normannorum (Duke of the Normans), into a false position wherein he could be convincingly portrayed to the other Princes as a faithless and perjured vassal and, therefore, a usurper.

A tremendous propaganda campaign preceded the Conquest which was written up afterwards (when all those who might have been able to refute it were dead, dispossessed or in exile) and a wonderfully executed pictorial version was made, the Bayeux Tapestry, to ensure that the message was conveyed even to those who could neither read nor write. So well-crafted was the campaign that much of it still impresses the minds of modern historians who are unable to free themselves from its insidious influence.

Most of this account is devoted to a stage by stage description of the Conquest itself and its effects on the nobility and clergy of England and upon the ordinary people. Duke Williams military preparations are described and his launching of the invasion. Much space is devoted to the Battle of Hastings and the Bastards terror campaign which intimidated the survivors into surrender. This is followed by an account of the reaction which set in when the true nature of Norman rule was revealed and the struggle, in vain, to remove the Norman Yoke. Then the story moves on to explain how the Norman settlement was carried out; the dispossession of the English, the Harrying of the North, the cleansing of the English Church and so on. It ends with the mysterious revolt by two Norman earls and the execution for involvement in it of Earl Waltheof, son of Cnuts great earl, Siward of Northumbria.

In writing this book I acknowledge my debt to the work of all those scholars whose works have been consulted and without which it would not have been possible. They are, of course, in no way responsible for the views and interpretations contained in it and any errors are my own.

I am grateful, as always, to the Librarian of St Johns College, Cambridge, for his permission to use the College Library.

In early January, 1066, Edward, King of the English, son of Aethelred II, lay dying in his Palace of Westminster. He had fallen ill some time towards the end of the previous November or early in December and, by the Feast of the Holy Innocents, 28 December, had been unable to attend the consecration of his beloved Westminster Abbey.

The nature of his illness was not understood by contemporaries and was complicated by suspicions of sickness of mind, that is a deep sorrow or melancholy, brought on by the way in which his wishes concerning the response to the threat of civil war in Northumbria had been frustrated. In modern times he would have been treated for depression. But that winter of 1065 was a harsh one with intense cold and the Kings illness became a physical one intensified by his age. By Christmas Eve his condition grew worse. On Christmas Day he could no longer disguise his weariness and arrangements were made for the consecration to be carried out in his absence.

As his condition became more serious he lost appetite and refused to eat, taking to his bed in distress as his condition worsened. By 28 December he had developed a fever being consumed by the fire of his illness and the aged king began to accept that his end was approaching. Becoming drowsy because of his bodys heaviness he lapsed into deep but troubled sleep and his attendants sought to rouse him. Much of what he said proved unintelligible to his hearers. Archbishop Stigand, who was present, remarked sotto voce to Earl Harold, He is broken with age and disease and knows not what he says. But then, after two or three days, he rallied enough to describe what was troubling him.

During his sleep, he is reported to have said, he had dreamed of two monks whom he had known as a young man in Normandy. They told him that they had a message for him from God. All the nobles and higher clergy of the kingdom, they said, were servants of the Devil and in consequence one year and one day after the day of your death, God has delivered all this kingdom, cursed by Him, into the hands of the enemy and devils shall come to roam at large through all this land with fire and sword and havoc of war. They had then related the parable of the Green Tree which was the description of something impossible and therefore meant that the day when the woes of England would cease was never. Ailred of Rievaulx adds that the King said The Lord has bent His Bow, the Lord has prepared His Sword. He brandishes it like a warrior. His anger is manifested in steel and flame.