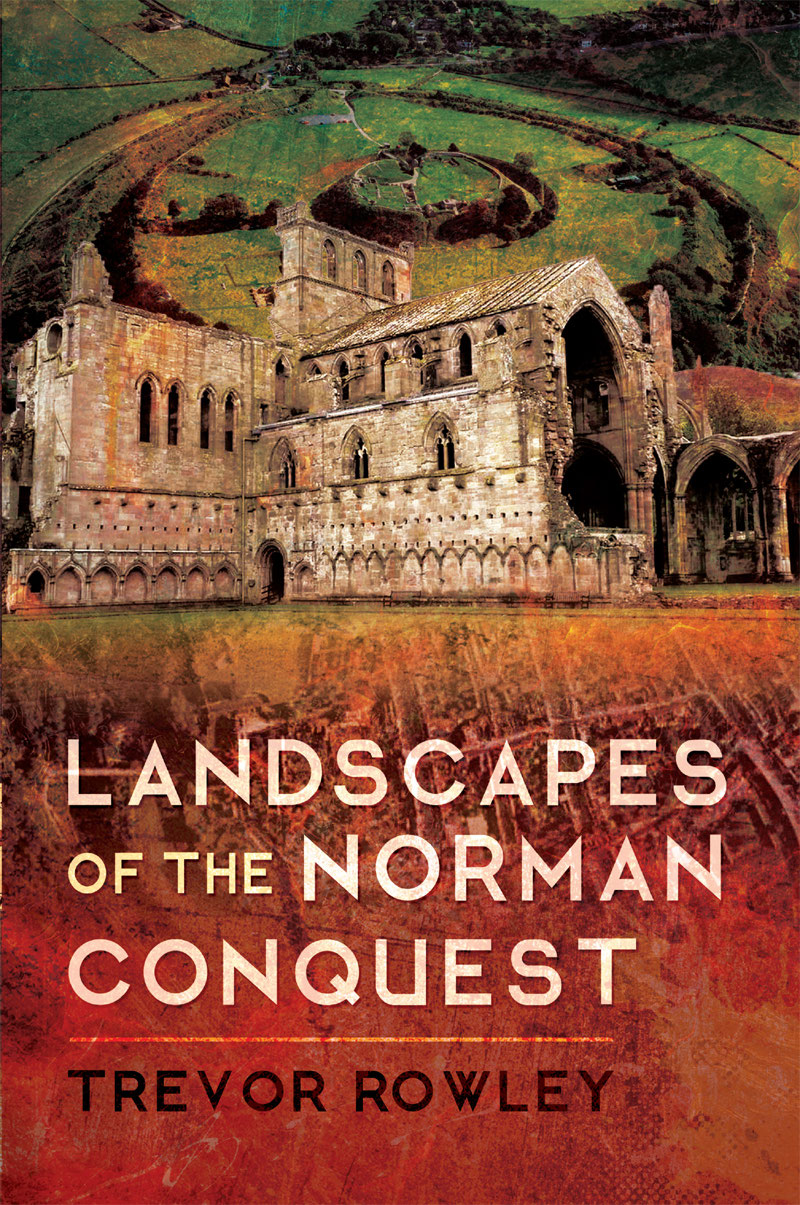

Landscapes of the

Norman Conquest

Landscapes of the

Norman Conquest

Trevor Rowley

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

Pen & Sword Archaeology

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Trevor Rowley, 2022

ISBN 978 1 52672 428 1

ePUB ISBN 978 1 52672 429 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52672 429 8

The right of Trevor Rowley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd. incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail: uspen-and-sword@casematepublishers.com

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Contents

Preface

Iwas brought up in Shropshire, a border county, where the imprint of Roger de Montgomery is still writ large in town, castle and church. My first degree was in geography at University College London, where the head of department was the great Domesday scholar H.C. Darby. Subsequently, I was privileged to have the father of landscape history, W.G. Hoskins, as my postgraduate tutor. Given that background it was perhaps inevitable that I would eventually try my hand at a book on the Norman landscape. In some respects, I wish I had written it thirty or forty years ago, when it would have been a relatively straightforward fieldwork-based narrative account of the Norman contribution to the English landscape. Although at that time there were still doubts in some quarters about the very existence of a distinctive Norman element in the landscape.

Today landscape history is a much broader, more complex discipline. In addition to a greatly expanded repertoire of technological aids, it incorporates the analysis of the importance of gender, mind and belief, display and spatial awareness. The male domination of Norman society reflected in the history is starkly illustrated in the Bayeux Tapestry, where out of 623 human images, just six are female; yet almost certainly the tapestry was mainly the work of seamstresses. Only in recent years has there been any serious attempt to redress this glaring gender imbalance. Where possible I have taken note of these and other developments, but cannot pretend that I have done them justice.

The Bayeux Tapestry has provided an invaluable source for illustrations. In the absence of other relevant contemporary material, I have used examples from both before and after the Norman era, and from outside Normandy and England. This book largely follows conventional landscape traditions, covering town, countryside, defence, the Church and so on, but it also looks at the historical geography of England in 1066 and the landscape of the invasion. The continuing influence of Rome on the Anglo-Norman world is acknowledged with a chapter of its own. The Norman landscape is construed in the broadest sense to include cultural landscapes of the arts as well as architecture. Due to the inter-related character of the main topics there is inevitably some overlap between chapters. The book concentrates on the Norman impact on England, with some attention given to Wales. Scotland is only dealt with superficially, and there is no attempt to cover the Normans in Ireland, although all three countries are, of course, more than worthy of independent treatment.

Trevor Rowley

Appleton, Oxfordshire

March 2022

Acknowledgements

Iam grateful to many people for the information, ideas and advice imparted to me during the writing of this book, notably Martin Biddle, James Bond, Bill Bower, Giles Carey, Michael Fieldsend, Jeremy Haslam, Martin Henig, Linda Kent, Robert Liddiard, Jane Rowley, Richard Rowley, Michael Sibly and Jan Ure. As always, any omissions, mistakes or misconceptions are entirely my own responsibility.

I would like to thank the city and people of Bayeux for permission to reproduce images from the Bayeux Tapestry. The authors of other photographs and plans are acknowledged in the text, while the Ordnance Survey map extracts are all taken from the first edition 25-inch series, England and Wales (1841-1920).

Introduction

[King William] implanted the customs of the French throughout England, and began to change those of the English.

(Hermann of Bury St Edmunds, c.1090)1

The Norman Conquest is the most celebrated watershed in English history. Its political and cultural consequences are well rehearsed, leading as it did to a new monarchy, aristocracy, architectural style and social system. 1066 represents a significant change in historical perception; it marks the point from which the present line of English monarchy is normally traced. It is also when there is a change from talking about peoples the Romans, the Saxons and the Vikings, to a dynastic compartmentalization of history the Normans, the Angevins, the Plantagenets, the Lancastrians, the Yorkists and the Tudors. Yet uniquely among this latter group, the Normans were also a people from the Continent, albeit one whose rule, strictly speaking, only extended from 1066 to 1154, and whose numbers were limited. The Norman Conquest was achieved by a relatively small Continental aristocratic elite and was not associated with any large-scale folk movement; in the first instance it was essentially the transposition of an aristocracy.

The short-lived Norman dynasty blended into a much longer line of earlier Saxon and later Angevin and Plantagenet monarchs. The people of this particular invasion were not really Norman but were native Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Scandinavians, Welsh and Scots, whose world was changed in response to the innovations and impositions of the Normans. The Normans were directly responsible for introducing relatively little that was completely new into the English landscape, but the political, social, economic and cultural changes they introduced acted as catalysts which induced the distinctive Anglo-Norman landscape of the late twelfth century, as well as establishing the template for the later medieval landscape. The Norman Conquest may have been more like earlier people invasions than it first appears; the transmission of new ideas from a small number of newcomers on a much larger native population was probably more common than is generally accepted. Such a transmission was certainly true of the Romans and may well have been the case of the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings.