The Mythical Battle

HASTINGS 1066

The Mythical Battle

HASTINGS 1066

Ashley Hern

ROBERT HALE

First published in 2017 by Robert Hale, an imprint of The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2017

Ashley Hern 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 71982 476 0

The right of Ashley Hern to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Contents

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks go to Dr Glenn Foard of the University of Huddersfield, for generously sharing with me his research on his excavations at Hastings and his extensive experience of battlefield archaeology. Alan Larsen shared his enthusiasm for the battle and his unique insights into the culture of the Hastings re-enactments. Jack Edwards of University College, Oxford, kindly allowed me to look at his thesis on Danish settlement. The staff at the Battle of Bosworth Visitor Centre responded helpfully to my many enquiries. My colleagues in the History Department at the Manchester Grammar School have tolerated my distraction and mental absences while writing this book with their customary grace particular thanks go to Simon Orth for reading some of the chapters. Alexander Stilwell has been a patient and supportive editor, and his perceptive comments have greatly improved the book.

This book would not have been possible without several years of teaching the Battle of Hastings to Sixth-formers at Manchester Grammar School, each of whom have subjected me to that idiosyncratic mixture of cynicism and curiosity that the British education system seems to provoke in later adolescence.

In many ways this book is also a testament to the inspirational history teaching of John Croasdell and Bill Reed, who eschewed modern teaching methods and instead used enthusiasm and an emphasis on knowledge and set me on the path to spending the majority of my life contemplating the past.

Above all else, I am grateful to Anne, Felix and Rufus for their love and encouragement.

List of Illustrations

Illustrations within the text (by Anne Crofts)

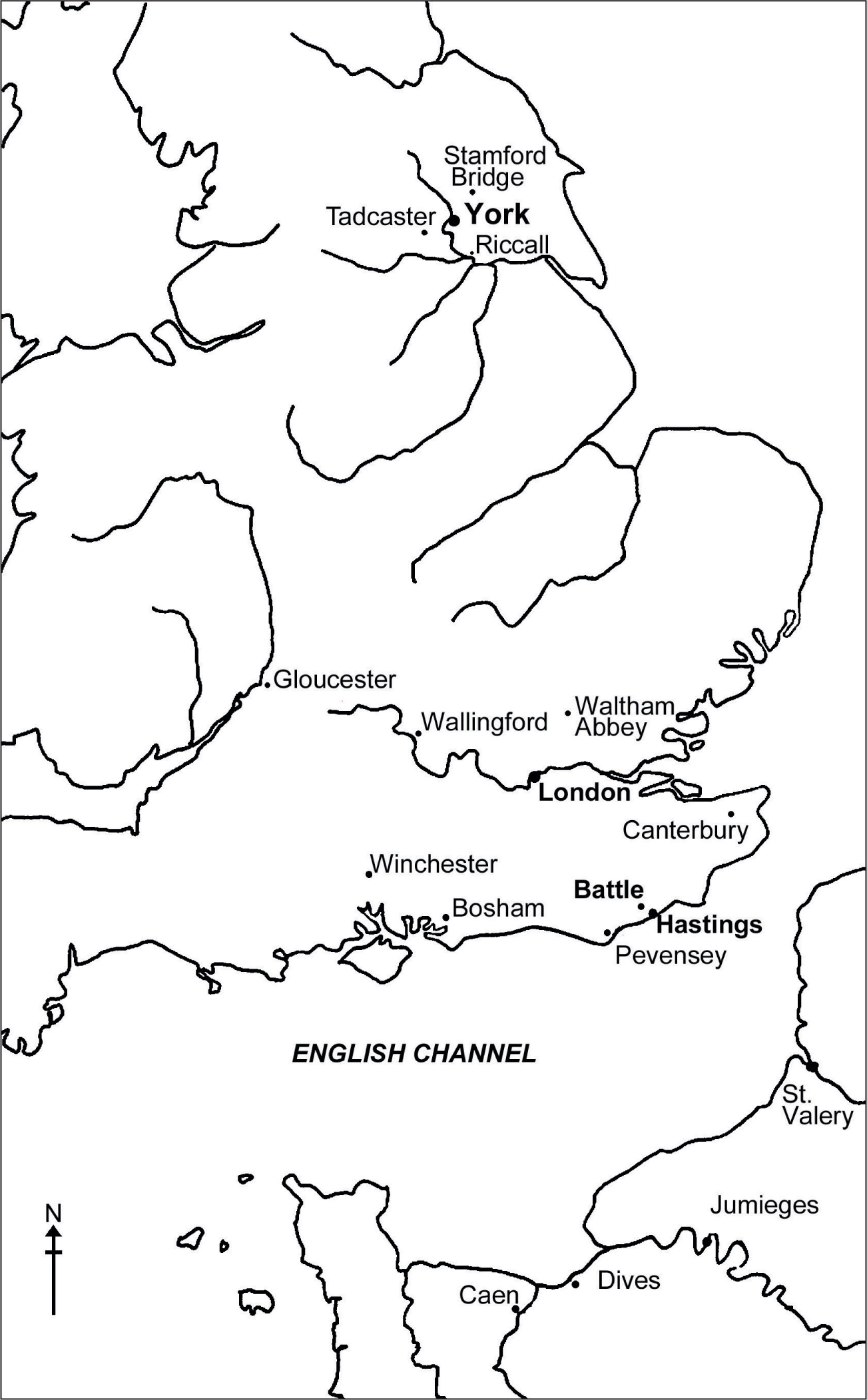

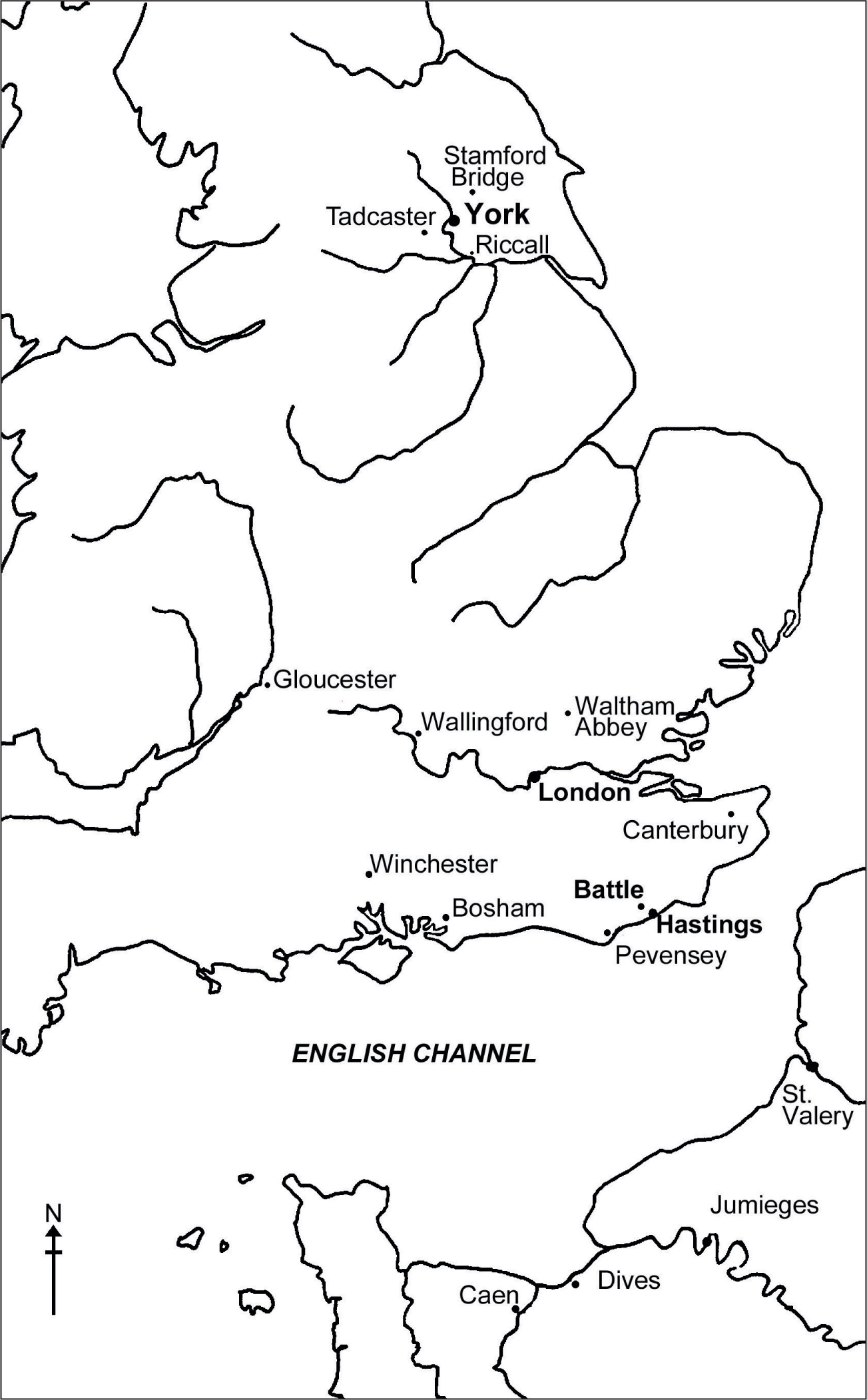

Map of England in 1066 with key location mentioned in the book.

Anglo-Saxon royal houses in the 10th and 11th centuries.

The English kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon period, c. AD 8001066.

The aristocratic dynasties of Godwin of Wessex and Leofric of Mercia.

Anglo-Saxon soldiers: peasant militia or light infantry? From the Bayeaux Tapestry.

Traditional map of the battles locations with modern features.

The Montfaucon engraving of King Harold II of 1732.

The Stothard engraving of King Harold II of 1819.

Colour plate section

Stone marking the traditional site of King Harold IIs tomb at Waltham Abbey.

Rear view of Harolds tomb (foreground) at Waltham Abbey in the shadow of the east end of the church.

Inscribed memorial stone marking the traditional location of Harold IIs death in the abbey church of Battle Abbey, which was moved in 2016. The outline of the now-demolished church can be seen marked on the grass in concrete and gravel.

Nick Austins proposed location of the battlefield at Crowhurst, East Sussex.

View of Caldbec Hill looking north from the Battle Abbey gatehouse

The south-facing slope of the traditional battlefield with the abbey at the summit of the hill, looking northwest to the English right flank.

The hill on the west side of the battlefield suggested as the site where the English victims of the feigned retreat sought refuge.

Looking north to the slope towards Battle Abbey across the nineteenth-century fishponds.

Map of England in 1066 with key locations mentioned in the book.

Introduction

BEING FACTUAL

What is a fact? This is a question I often ask any Sixth-form student if they tell me that they want to study history at university. A look of bemusement on the students face usually results, an expression that seems to appear with increasing frequency as the years pass. We know what a fact is, sir, they reply. Its what you always demand we put more of in our essays. Are you finally losing it, sir? We have had our suspicions for some time!

After some cautious discussion, I can usually persuade them to humour me and we then collectively attempt to take an empirical approach to the matter.

What about the Battle of Hastings?

There are nods of agreement. Like most school pupils in England, they studied this particular battle when they began their history education at secondary school. Some studied the battle at primary school; a few studied it again in their Sixth-form studies. Nor is this a parochial concern: teaching about the Battle of Hastings is a national phenomenon. History teachers, just like King Harold II, will never escape the battle unless they leave the classroom and ascend to greater things, like Duke William of Normandy.

Below is a composite version of a classroom exchange on this issue in the form of a dialogue (with apologies to Plato).

ME: Where did the battle take place?

PUPILS: Hastings, of course, sir!

ME: Did it?

PUPILS: Well, alright. It took place at Battle but thats near Hastings.

ME: So, why do we call it the Battle of Hastings then? One could argue that by the standards of modern warfare, it would not be considered a battle at all it lasted a day and we cant be sure how many people were fighting on both sides. The Battle of the Somme in 1916 involved millions of soldiers, resulted in hundreds of thousands of casualties and lasted for four months. Would it not be better to refer to what happened in 1066 as a skirmish in Sussex? Skirmishes can have devastating political consequences, after all. Look at Prince Llewellyn ap Gruffudd, whose death in a skirmish at Builth in 1282 heralded the conquest of Wales by Edward I of England.

PUPILS: But the battle led to the conquest of England. You cant dismiss it as just a skirmish. We should call it the Battle of Hastings as thats what people have always called it. Its traditional. People know what you are referring to.

ME: Who decided this tradition? When did it begin?

PUPILS: We dont know! Ask us another one.

ME: OK, so when was the Battle of Hastings actually fought?

PUPILS: 1066!

ME: What date?

ONE VERY BRIGHT PUPIL: Fourteenth of October? It was the anniversary a few months ago! [This conversation usually occurs in January]

ME: Officially but that was according to the old Julian calendar. When this was revised and Britain was brought into line with the Gregorian calendar in 1752, the anniversary of the battle officially became the twenty-fifth of October. OK, what about the year 1066 what dating system does this use?

PUPILS: The Christian dating system.

ME: Doesnt this reflect one cultural perspective? According to the Islamic dating system, the year the battle took place was AH 459. In the Jewish calendar, the year was 4827. In the Mayan Long Count, the date was 0.12.0.0.18 .

I will allow the rest of the scene to unfold in your imagination. Confusion and irritation are the two principal emotions this conversation provokes amongst my pupils, but before being accused of semantic pedantry and postmodern flippancy, there is a serious point to be made as part of a wider attempt to make my pupils think more critically about the information that they think they know. We believe that the Battle of Hastings is an important event because of the way our understanding of the past has been organized. The famous Whig interpretation of history, which emerged in the eighteenth century, remained a standard view amongst professional historians well into the twentieth century. Whig is the term given to a loose affiliation of individuals with common political beliefs that developed in support, amongst other things, of constitutional monarchy, the Hanoverian succession and parliamentary sovereignty. This viewpoint saw the Norman Conquest as the end of a Golden Age in which native English customs of freedom and equality were destroyed by the oppressive rule of foreigners. For writers such as Thomas Macaulay and his successors, English history after 1066 consisted of a series of struggles to regain these lost freedoms, through Magna Carta, the Reformation, the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution of 1689.

Next page