CHAPTER I

A Quarrel

T he great Abbey of Westminster was approaching its completion; an army of masons and labourers swarmed like bees upon and around it, and although differing widely in its massive architecture, with round Saxon windows and arches, from the edifice that was two or three generations later to be reared in its place,to serve as a still more fitting tomb for the ashes of its pious founder,it was a stately abbey, rivalling the most famous of the English fanes of the period.

From his palace hard by King Edward had watched with the deepest interest the erection of the minster that was the dearest object of his life. The King was surrounded by Normans, the people among whom he had lived until called from his retirement to ascend the throne of England, and whom he loved far better than those over whom he reigned. He himself still lived almost the life of a recluse. He was sincerely anxious for the good of his people, but took small pains to ensure it, his life being largely passed in religious devotions, and in watching over the rise of the abbey he had founded.

A town had risen around minster and palace, and here the workmen employed found their lodgings, while craftsmen of all descriptions administered to the wants both of these and of the nobles of Edwards court.

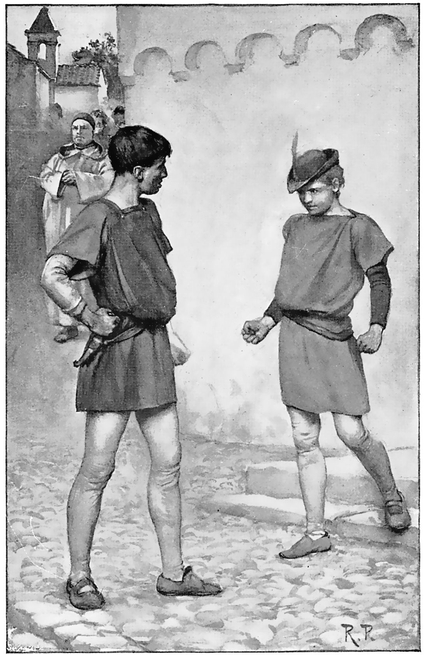

From one of the side doors of the palace a page, some fifteen or sixteen years of age, ran down the steps in haste. He was evidently a Saxon by his fair hair and fresh complexion, and any observer of the time would have seen that he must, therefore, be in the employment of Earl Harold, the great minister, who had for many years virtually ruled England in the name of its king.

The young page was strongly and sturdily built. His garb was an English one, but with some admixture of Norman fashions. He wore tightly-fitting leg coverings, a garment somewhat resembling a blouse of blue cloth girded in by a belt at the waist, and falling in folds to the knee. Over his shoulders hung a short mantle of orange colour with a hood. On his head was a cap with a wide brim that was turned up closely behind, and projected in a pointed shovel shape in front. In his belt was a small dagger. He wore shoes of light yellow leather fastened by bands over the insteps. As he ran down the steps of the palace he came into sharp contact with another page who had just turned the corner of the street.

I crave your pardon, Walter Fitz-Urse, he said hurriedly, but I was in haste and saw you not.

The other lad was as clearly Norman as the speaker was Saxon. He was perhaps a year the senior in point of age, and taller by half a head, but was of slighter build. The expression of his face differed as widely from that of the Saxon as did his swarthy complexion and dark hair, for while the latter face wore a frank and pleasant expression, that of the Norman was haughty and arrogant.

You did it on purpose, he said angrily, and were we not under the shadow of the palace I would chastise you as you deserve.

The smile died suddenly out from the Saxons face. Chastise me! he repeated. You would find it somewhat difficult, Master Fitz-Urse. Do you think you are talking to a Norman serf? You will please to remember you are in England; but if you are not satisfied with my apology, I will ride with you a few miles into the country, and we will then try with equal arms where the chastisement is to fall.

The Norman put his hand to his dagger, but there was an ominous growl from some men who had paused to listen to the quarrel.

You are an insolent boor, Wulf of Steyning, and some day I will punish you as you deserve.

FITZ-URSE PUT HIS HAND TO HIS DAGGER

Some day, the Saxon laughed, we shall, I hope, see you and all your tribe sent across the Channel. There are few of us here who would not see your backs with pleasure.

What is this? an imperious voice demanded; and turning round, Wulf saw William, the Norman Bishop of London, who, followed by several monks and pages, had pushed his way through the crowd. Walter Fitz-Urse, what means this altercation?

The Saxon ran against me of set purpose, my lord, Walter Fitz-Urse said, in tones of deep humility, and because I complained he challenged me to ride with him into the country to fight, and then he said he hoped that some day all the Normans would be sent across the Channel.

Is this so? the prelate said sternly to Wulf; did you thus insult not only my page, but all of us, his countrymen?

I ran against him by accident, Wulf said, looking up fearlessly in the prelates face. I apologized, though I know not that I was more in fault than he; but instead of taking my apology as one of gentle blood should do, he spoke like a churl, and threatened me with chastisement, and then I did say that I hoped he and all other Normans in the land would some day be packed across the Channel.

Your ears ought to be slit as an insolent varlet.

I meant no insolence, my Lord Bishop; and as to the slitting of my ears, I fancy Earl Harold, my master, would have something to say on that score.

The prelate was about to reply, but glancing at the angry faces of the growing crowd, he said coldly:

I shall lay the matter before him. Come, Walter, enough of this. You are also somewhat to blame for not having received more courteously the apologies of this saucy page.

The crowd fell back with angry mutterings as he turned, and, followed by Walter Fitz-Urse and the ecclesiastics, made his way along the street to the principal entrance of the palace. Without waiting to watch his departure, Wulf, the Saxon page, pushed his way through the crowd, and went off at full speed to carry the message with which he had been charged.

Our king is a good king, a squarely-built man,whose bare arms with the knotted muscles showing through the skin, and hands begrimed with charcoal, indicated that he was a smith,remarked to a gossip as the little crowd broke up, but it is a grievous pity that he was brought up a Norman, still more that he was not left in peace to pass his life as a monk as he desired. He fills the land with his Normans; soon as an English bishop dies, straightway a Norman is clapped into his place. All the offices at court are filled with them, and it is seldom a word of honest English is spoken in the palace. The Norman castles are rising over the land, and his favourites divide among them the territory of every English earl or thane who incurs the kings displeasure. Were it not for Earl Harold, one might as well be under Norman sway altogether.

Nay, nay, neighbour Ulred, matters are not so bad as that. I dare say they would have been as you say had it not been for Earl Godwin and his sons. But it was a great check that Godwin gave them when he returned after his banishment, and the Norman bishops and nobles hurried across the seas in a panic. For years now the king has left all matters in the hands of Harold, and is well content if only he can fast and pray like any monk, and give all his thoughts and treasure to the building of yonder abbey.

We want neither a monk nor a Norman over us, the smith said roughly, still less one who is both Norman and monk. I would rather have a Dane, like Canute, who was a strong man and a firm one, than this king, who, I doubt not, is full of good intentions, and is a holy and pious monarch, but who is not strong enough for a ruler. He leaves it to another to preserve England in peace, to keep in order the great Earls of Mercia and the North, to hold the land against Harold of Norway, Sweyn, and others, and, above all, to watch the Normans across the water. A monk is well enough in a convent, but truly tis bad for a country to have a monk as its king.