Conquered

Conquered

The Last Children of Anglo-Saxon England

Eleanor Parker

Contents

Then King Harold was slain... |

A surviving area of the Fens near Ely |

Peterborough Cathedral |

Bourne, Lincolnshire |

The comet of 1066 on the Bayeux Tapestry |

Ely Cathedral |

Peterborough Cathedral |

A nineteenth-century image of Hereward |

Edmund Ironside and his descendants in a fourteenth-century manuscript |

Edgar clito |

St Margaret depicted in a fourteenth-century manuscript |

The marriage of Margaret and Malcolm, in a modern window in St Johns church, Busbridge, Surrey |

St Margaret of Scotland, from Busbridge, Surrey |

St Margarets chapel in Edinburgh Castle |

Edith/Matilda and Henry I in a fourteenth-century manuscript |

Romsey Abbey |

The coronation of Harold Godwineson on the Bayeux Tapestry |

A church dedicated to St Olaf in Chichester, probably reflecting the influence of the Godwine family |

Prayers to St Olaf in a manuscript from eleventh-century Exeter |

The siege of Exeter in one version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle |

St Giless Hill, Winchester |

Crowland Abbey, the place of Waltheofs burial |

A medieval statue of Waltheof at Crowland Abbey |

Eadmer depicted in a twelfth-century manuscript |

An example of Eadmers scribal work |

Osbern depicted in a manuscript from Christ Church |

Canterbury Cathedral |

St lfheah in the twelfth-century Passionale produced at Christ Church, a set of manuscripts probably made under Eadmers supervision |

Canterbury annals for 106676, noting the death of Edward the Confessor, the destruction and rebuilding of Christ Church and the execution of Waltheof |

A reconstruction of the Anglo-Saxon cathedral at Canterbury, based on Eadmers description |

I am grateful to everyone who has helped in the preparation of this book, but I want to acknowledge one group of people in particular. The generation of children and adolescents whose lives were disrupted by the Norman Conquest has been an interest of mine for several years. However, the last stages of this book were written in 20201, during the pandemic and a course of successive lockdowns. Throughout this time I was teaching undergraduate students, most of them around the same age as many of the subjects of this book were at the time of the Norman Conquest. These young people, too, were coping with upheaval, loss and a sudden change in the expected course of their lives. They faced it all with courage and determination, but it is no doubt an experience that will remain with them. This book is dedicated to them and to my nieces, Francesca and Lucia.

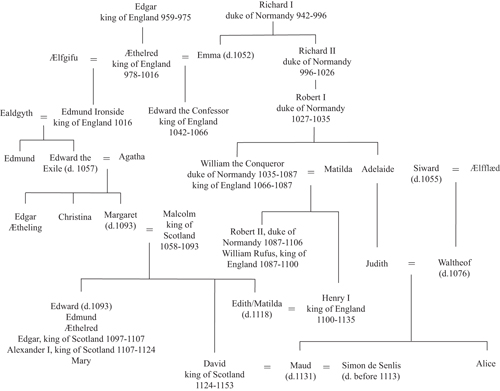

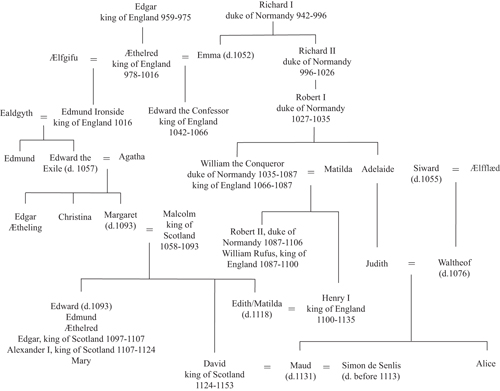

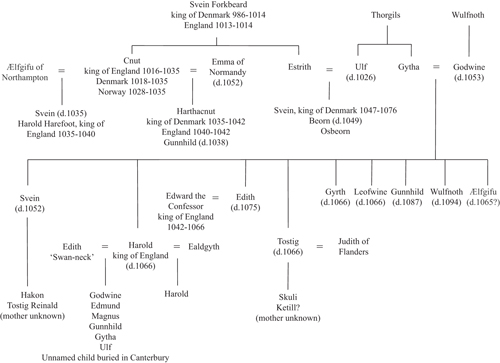

Table 1The families of Margaret and Waltheof

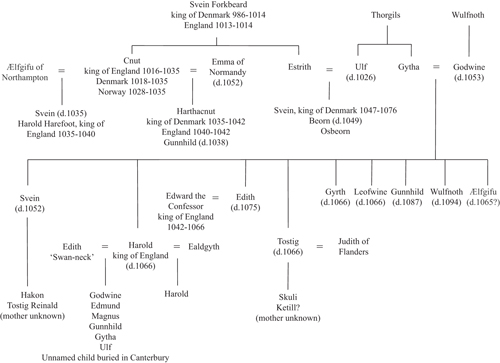

Table 2The family of Gytha and Godwine

Sometimes events occur which are so sudden and so life-changing in their implications that they alter an entire society. They cleave time in two: life before and life after. They define generations, dividing society into those who remember the world before the new reality and those who have never known anything else.

The Norman Conquest of England was one of those events. For almost a thousand years, it has been seen as a defining moment in English history the end of one age and the beginning of another, sometimes even (despite all evidence to the contrary) the starting point of English history itself. The single date 1066 is deeply embedded in British culture; almost from the first it was interpreted as a pivotal moment, a watershed, after which nothing would be the same ever again.

This book explores the lives of those who had a unique perspective on this moment in history: the generation born on the eve of the conquest, between the late 1040s and early 1060s, who were in their childhood or teens in 1066 and grew up in its aftermath. In most cases too young to have a direct role in the events of that year but old enough to perceive what was happening, they would find their adult lives shaped by the influence of new forces rapidly altering the world into which they had been born. At the time of the conquest, those in their teens were entering adulthood old enough to marry, hold lands or fight in battle but were unlikely to have yet had much experience of leadership or political life and were still to a large degree dependent on the decisions of their elders or those in authority over them.Others were young children, made vulnerable by the loss of parents or home and affected by the conquest in ways that would influence them for the rest of their lives. In the years after 1066, as the effects of the conquest took hold, some members of this generation began to play an active part in rebellion against Norman rule, while others chose or were forced into submission; some left the country; some did little but watch and observe the changes they were witnessing.

The effect of the conquest on the lives of this generation of English children was not by any means wholly negative. While some struggled to find a place for themselves in the post-conquest world, others flourished, benefitting from new encounters and opportunities for cultural exchange. But whatever their individual experiences, they all faced lives which turned out very differently from the ones they might have expected to live. In this book, we will explore both change and continuity across the conquest from a variety of different perspectives through the lives of members of this generation, as they grew up into men and women, nuns and queens, warriors and monks. We will consider what these individual life stories can tell us about English society and culture in the decades after the Norman Conquest, as well as how this crucial period was remembered in later centuries. This generation were the last children of Anglo-Saxon England, but they were also the fathers and mothers of the country England was to become.

English, Normans, Anglo-Normans

Though in the past the Norman Conquest was often seen as the starting point of English history and identity, few historians would now subscribe to that view. Such a starting point (in so far as it is helpful to look for one at all) must be sought at least two or three centuries earlier; by the eleventh century, It is worth emphasizing this point, because one of the most significant features of the decades after the Norman Conquest was the survival, in an evolving and adapting form, of that identity and the narrative of English history which was bound up with it. Partly for reasons of convenience, historians speak of a transition from Anglo-Saxon to Anglo-Norman England, but contemporary terminology was more fluid and flexible than either of those formulations: the designation English survived, but its meaning underwent important change.