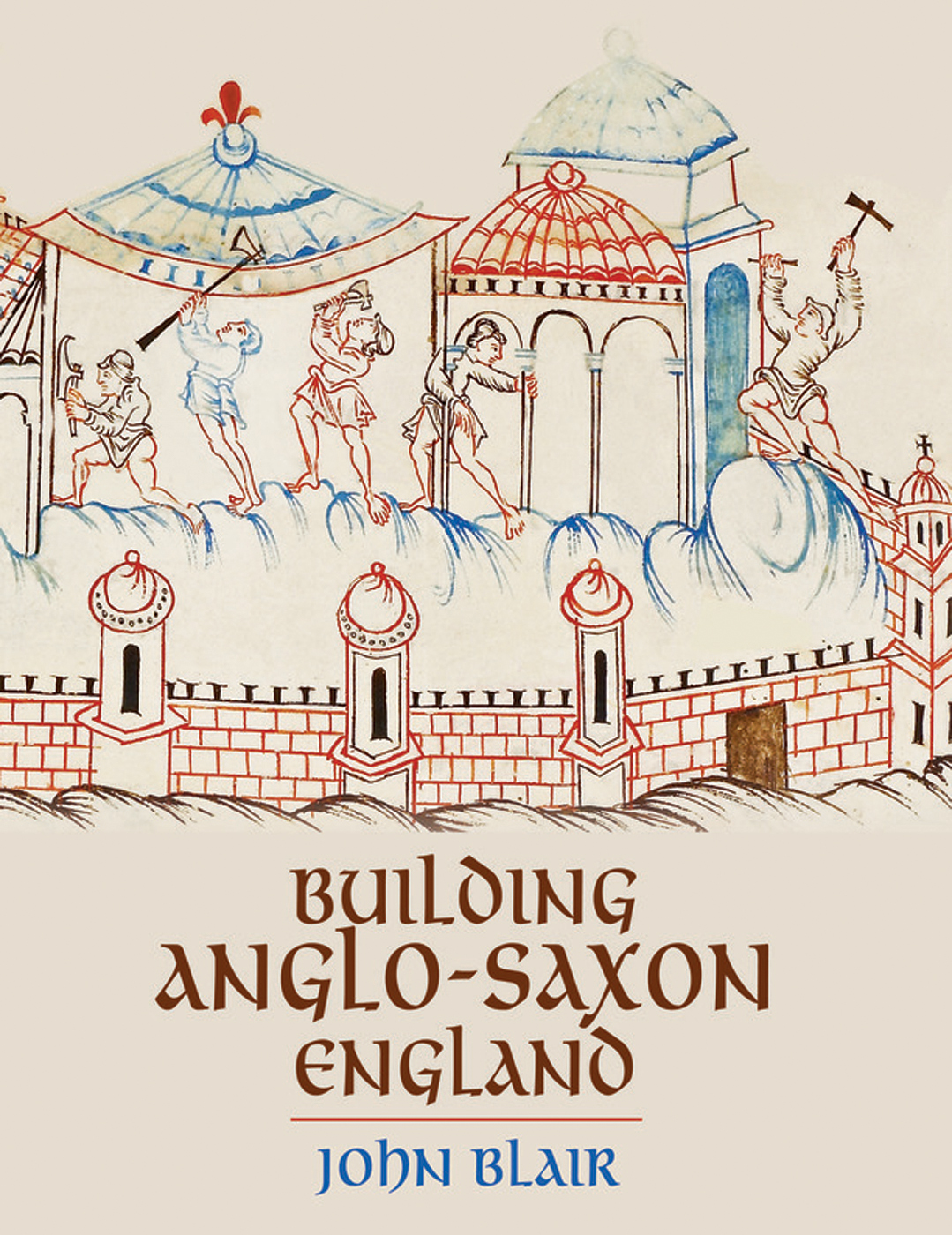

Building Anglo-Saxon England

Building Anglo-Saxon England

Building Anglo-Saxon England

Building Anglo-Saxon England

John Blair

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2018 by John Blair

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: illumination from the Harley Psalter, MS 603, f.66v, 11th century / The Image Works

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Blair, John, 1955 author.

Title: Building Anglo-Saxon England / John Blair.

Description: Princeton, NJ : Princeton University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017031653 | ISBN 9780691162980 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Great BritainHistoryAnglo-Saxon period, 4491066. | LandscapesEnglandHistoryTo 1500. | Land settlementEnglandHistoryTo 1500. | Landscape archaeologyEngland. | Anglo-Saxons. | EnglandAntiquities.

Classification: LCC DA152 .B593 2018 | DDC 942.01/7dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017031653

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For

Kanerva

Kanerva

Contents

Contents

Illustrations

Illustrations

Preface and Acknowledgments

Preface and Acknowledgments

Looking back on an Oxford research career in which English topography has loomed large, I recall the acid comment of one distinguished predecessor, fifty years ago, about another distinguished predecessor in the twelfth century. In 1963, W. G. Hoskins wrote:

The very first book to be read in the nascent University of Oxford, in the year 1184, was the Topography of Ireland, read aloud to the assembled masters and scholars by Girald Cambrensis over the space of three whole days. As little time at Oxford has been devoted to the study of topography since then, one might suppose that Girald had effectively killed the subject by this solo performance.

Ten years after Hoskins wrote, I arrived in Oxford as an undergraduate and found the study of topography very lively. But that was in the milieu of the University Archaeological Society: such activities were extracurricular. Informally, tutors were immensely supportive of my interests, but the undergraduate course in history did not venture far outside the written record. Forty years on, the welcoming of topography, archaeology, and art history from the fringes of historical enquiry to its core has been a dramatic change. If Hoskins could come back now, he would surely take a more positive view; if Gerald of Wales could come back, he would find that the ethnography and popular culture that so fascinated him are now mainstream topics.

It is a mark of that transformation that the Electors to the James Ford Lectureship in British History invited me to give the Ford Lectures for 2013, and were content for me to choose a topographical theme. Encouraged by the invitation, I applied to the Leverhulme Trustsuccessfully, as it happily turned outfor a three-year Major Research Fellowship devoted to the intensive study of the Anglo-Saxon built landscape and culminating in the lecture series. This bookthe main outcome of that unique and wonderful interlude in my professional career as an Oxford college tutorembodies the substance of those Ford Lectures, although much enlarged and rearranged.

It was never likely that a project on this scale would result in just one publication, and as the book has grown it has generated offshoots. Some of my ideas about regionality, forms of , and what is said there can eventually be expanded in the light of our conclusions.

My first words of thanks must go to the Leverhulme Trust; without it, none of this would have been possible. At a time when so many funded projects are forced into thematic and collaborative straitjackets, the Leverhulmes unbureaucratic, common-sense approach is a lifeline. And I can never repay my debt to my three refereesthe late Nicholas Brooks, Jinty Nelson, and Michael Lapidgefor their confidence in me. Chris Wickham and Aileen Mooney gave support and good advice in formulating the proposal. John Baines and Roberta Gilchrist may remember the bottle of champagne over which the scheme was hatched.

I could not, however, have taken up the Leverhulme award without the cooperation of my teaching colleagues in Oxford, both at The Queens College and in the History Faculty: special thanks to John Davis and Christine Peters, who coped with my absence; to Jonathan Jarrett, who covered my tutorial teaching; to the College library staff; and to the staff in the College office, who put up with my printing and copying. Among its many other qualities, Queens affords a most agreeable research environment, and everyone was cheerfully tolerant of my semidetached but regular presence. Data collection would have been slower without the Sackler Librarys comprehensive and accessible holdings.

Among Oxford colleagues and friends, four were especially important. Richard Bradley helped crucially at the planning stage; in mining grey literature I have followed in his footsteps, and his insights into both late prehistoric and early medieval archaeology have always stimulated. Ann Cole, Rosamond Faith, and Helena Hamerow were constantly on hand to react to my ideas and to offer advice; their influence has been profound, though all of them will find places where (rightly or wrongly) I have maintained my own eccentric line in defiance of their raised eyebrows. The text has been much improved by the criticisms of the five people who read it right through (Kanerva Blair-Heikkinen, Helena Hamerow, Christopher Whittick, and Princetons anonymous readers), and the other colleagues who read sections.

Writing a book of this scope, at a time when study of the early English landscape enjoys such unprecedented vitality and when new data are accumulating so fast, has been both a privilege and a challenge. The academic community has given me stimuli to new lines of thought and enquiry that are too numerous to remember or record, but there are some peoplein addition to those thanked above and belowwho must be named: the late Mick Aston, Lesley Abrams, John Baker, Mark Barratt, Steven Bassett, Stephen Baxter, Jill Bourne, Stuart Brookes, Alex Burghart, Jan-henrik Fallgren, Michael Fradley, Mike Fulford, Mark Gardiner, Helen Geake, Helen Gittos, Teresa Hall, Hajnalka Herold, Richard Jones, Susan Kelly, George Lambrick, John Ljungkvist, Adam McBride, Maureen Mellor, Martin Millett, Richard Jones, Carenza Lewis, Rory Naismith, Dominic Powlesland, Andrew Reynolds, Stephen Rippon, Nicolas Schrder, Sarah Semple, Christopher Smart, Paul Stamper, Letty Ten Harkel, Gabor Thomas, Duncan Wright, Barbara Yorke. At intervals Christopher Whittick has maintained my morale, not least in working out a title for this book as we tramped up to the Caburn hillfort.

Next page

Building Anglo-Saxon England

Building Anglo-Saxon England