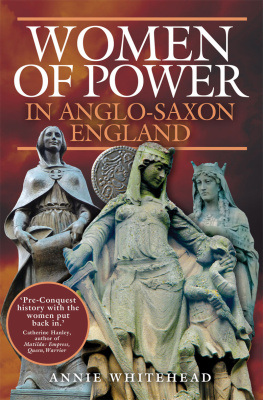

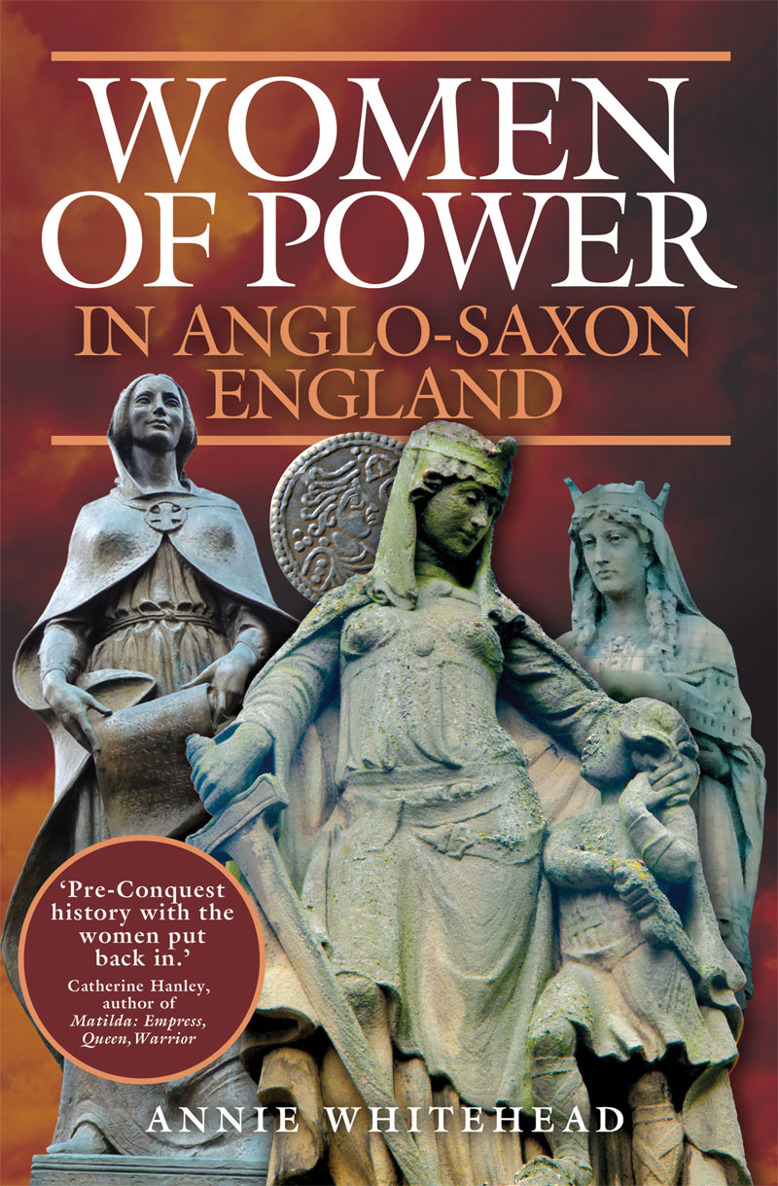

WOMEN OF POWER IN

ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND

WOMEN OF POWER IN

ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND

ANNIE WHITEHEAD

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Annie Whitehead, 2020

ISBN 978 1 52674 811 9

eISBN 978 1 52674 812 6

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52674 813 3

The right of Annie Whitehead to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Acknowledgements

Writing a book is a solitary experience, but there comes a point when no author can go it alone. Ive always been interested in the Anglo-Saxons, and readers of my novels have commented that the female characters are often the strongest. From the persuasive, forceful and sometimes downright uncompromising women of the seventh century, to thelfld Lady of the Mercians and Queen lfthryth, all have been subjects of my fiction. As Ive begun to write more nonfiction, Ive been keen to highlight the lives and careers almost forgotten and scarcely written of the other queens, princesses, dowagers, abbesses and evil women of the pre-Conquest period. My first nod of gratitude must therefore go to Claire Hopkins, who listened to my ideas and commissioned the book.

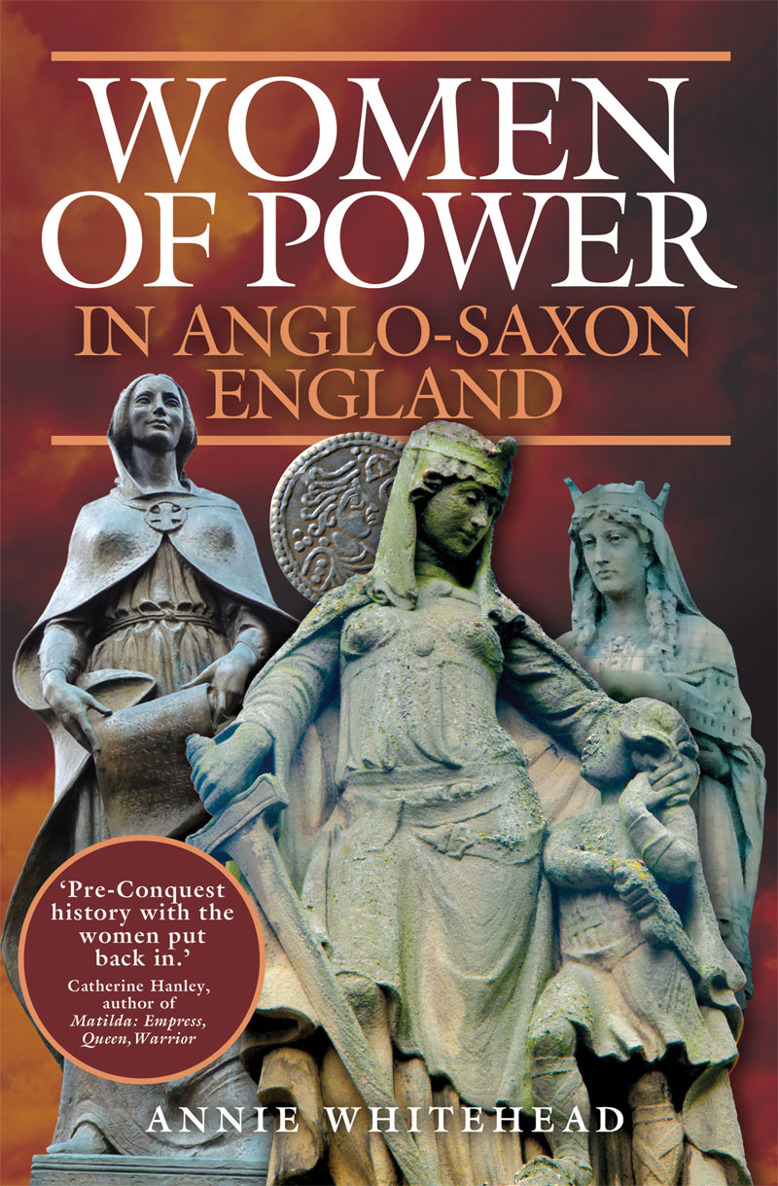

Many people have provided practical help and I would like to thank Lin and David White of Coinlea Services for producing the family trees from my sketches. Im also grateful to Dr Cathy Guthrie, Hon. Secretary, Tourism Management Institute and Julie Edwards, Senior Tourism Officer at Thanet District Council for their assistance regarding the history of Minster-in-Thanet and to Sister Aelred of the community of Minster Abbey for providing the beautiful photos of the Anglo-Saxon fabric of the building. Mention must also be made of the people who kindly supplied additional images for me to use. Thank you to David Satterthwaite, David Webster, Mia Pelletier, Canon Dagmar Winter, Rector of Hexham Abbey and Esther Russell, Hexham Abbey Parish Administrator, and to Gary Marshall from All About Edinburgh for the image of St Margarets statue, shown on the front cover.

Thanks as always must go to Ann Williams, whose inspirational teaching when I was her undergraduate student gave me the bug and who has continued to offer advice and information ever since. I should particularly like to express my gratitude to Ann for graciously allowing me access to two of her papers pre-publication and for sending me a copy of a third, published, paper. Vanessa King has been endlessly patient with me as I sought to pick her brains, and Marie Hilder has also been a source of information and inspiration. Im grateful to both for their insights.

There are still times during the writing of a book when the author feels isolated. At those moments my Pen & Sword stable-mates, Sharon Bennett Connolly and Helen Hollick, have always been at the end of, if not a phone, then an email or message. I thank them for their support and friendship.

Introduction

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , commissioned by Alfred the Great in the ninth century, tells the story, year by year, of the major events in English history. Yet up to the year 1000 there are fewer than twenty occasions where a woman is mentioned by name. Two queens who came to prominence after that time are mentioned more, but before that we are given only the odd cursory reference. Those two queens, Emma and Edith, both had their lives documented in more depth, but in works which were commissioned by, and thus heavily biased in favour of, the queens themselves. In both cases the Encomium Emm Regin and the Life of King Edward the Confessor there was a specific political purpose behind the writing, and the queens are portrayed in a flattering light. Other information about royal women comes to us from the hagiographies, or Lives , of the female saints, but in many cases these were written by, or for, the religious communities which claimed possession of the relics of those saints and so again, were biased towards those houses and against rival claimants. (Arguments about the possession of relics becomes somewhat of a recurring theme during this period.)

Luckily, we have other records besides the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Lives , but even in these, some women talk to us more than others, depending on the sources and their reason for having been written. We only know about these women because someone had a particular motive for writing about them and we are often only presented with one side of the story. In the earlier period we hear far more about the women of the Church, simply because this is what interested the earliest writers, for example the venerable Bede. We have wild tales even about those revered as pious nuns of escape from hot ovens and down sewers, of women bringing animals and even themselves back to life, all of which seem fantastic but were told to serve a purpose.

The woman who escaped down a sewer was protecting her chastity and one who came back to life after being killed was demonstrating her sanctity whilst also solving a murder case. Even the darker tales three-in-a-bed romps and the murder of innocent children were told to fit a particular narrative and in amongst the escapology, the saintly virgins and the murderous termagants, we have royal consorts who exerted great influence, not necessarily as queens, but through their children. Despite the rights and privileges and their protection in theory by the laws of the land, noblewomen were still prized, whilst not necessarily being valued and there is more than one story of abduction. The bloodline of royal women was something they conferred upon their offspring and it helped to strengthen claims of their husbands and sons.

Often, in fact, we find that women are only referred to in terms of being someones wife or daughter and perhaps we should not be surprised to find an anti-feminist tone in the religious writings of the early medieval period. However, in the very earliest years of the Christian conversion, the abbesses held a great deal of authority without the Church seeming to mind, and in the later period to be a royal mother was to be the power behind the throne.

Next page