England and Wales

1

The Lions Cubs (10541087)

From the death of William the Conqueror to that of the last of his sons was a span of some forty-eight years. For about twenty of these, the sons fought each other in turn to obtain supremacy in the lands their father had conquered, while the victor spent a further twenty-two years trying to hold on to what he had gained. Small wonder, perhaps, that he provided only a single legitimate male heir to inherit the whole of his achievements, but even that plan was overthrown by a totally unexpected and freakish tragedy.

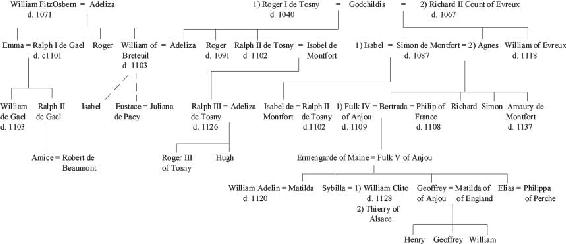

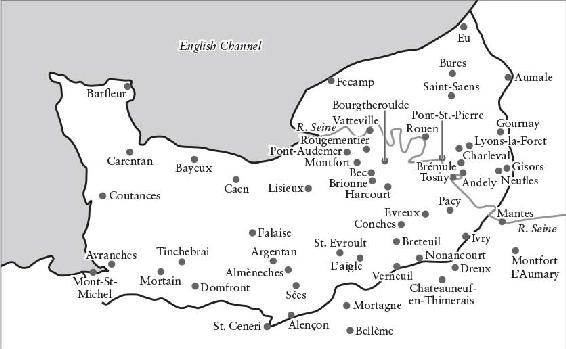

Throughout this time of struggle, Normandy suffered by far the worst of the violence, with neighbouring lands of France, Flanders and Anjou drawn into the fray at different points in the conflict.The Holy Roman Emperor and even the pope were also involved. England, though more peaceful, bore the brunt of paying for the fighting, albeit with an incidental benefit of developing a smooth-running system of administration and justice that operated well, even in the prolonged absence of her king.

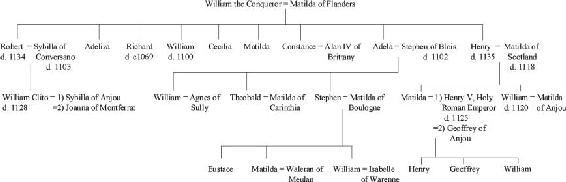

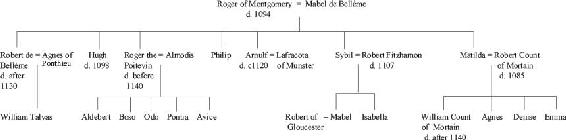

A turbulent family, then, that of the Conqueror, though no doubt it would be foolish to expect anything else, given the background of the man at its head. William, bastard son of Robert Duke of Normandy and a tanners daughter, had been thrust into the limelight at the age of six or seven when his father nominated him as his heir before departing on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. When Robert died on the way home the following year, the child became, in name at least, Duke of Normandy. Thereafter, however, despite the Norman nobility having sworn oaths of loyalty to him, he had to fight, and fight hard, to make that title a reality. Further fighting would turn the name of William the Bastard into William the Great, and ultimately William the Conqueror, but it left its mark on a man most frequently described as grim, stern and formidable.

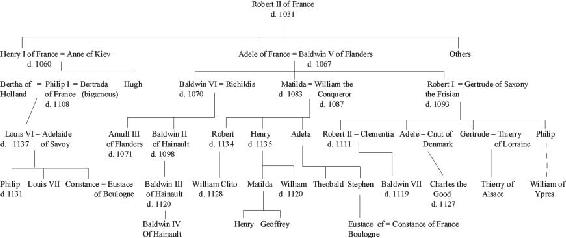

He had to struggle, too, for his wife, Matilda, daughter of Count Baldwin of Flanders and niece of the French king, Henry. The very fact that William asked for her hand in marriage shows the boldness of the young duke, only just secure himself in his duchy. It was certainly a prestigious match and something of a surprise when her father consented, but an alliance of Flanders, Normandy and France had advantages for all at the time, when the perceived enemy was the Holy Roman Emperor. The marriage, however, was forbidden by the pope, himself a German and no doubt well aware of the interests of the German Emperor, even if they were not explicitly stated. The excuse given was that William and Matilda were too closely related. Looking at their ancestors, it is hard to see how the pope could come to this conclusion, even though it was a common ploy at the time to prevent an inconvenient marriage. The sole connection seems to be that Williams aunt was the second wife of Matildas grandfather. Matilda herself, though, was descended from the first wife.

With or without the popes permission, William went ahead with the marriage. Forbidden in 1049, it may have happened as early as the following year when Matildas name first appeared as witness to a Norman charter. It was certainly a fait accompli by the time the prohibition was quietly withdrawn in 1053, at which time the pope himself was effectively a prisoner of the Normans from southern Italy, and at least three children of the marriage had been born before it was formally approved by a new pope in 1059. The penance demanded for the initial disobedience is still readily visible today in Williams favourite city of Caen. The Abbaye aux Hommes, founded by William, stands a few hundred yards away from the Abbaye aux Dames, founded by Matilda, a testimony in stone to a partnership that was equally solid and long-lasting.

Although certainly a diplomatic triumph, there may even have been a little love there right from the start. It has been suggested that William first laid eyes on Matilda at the court of her uncle, Henry of France, which is plausible, though the story attached to this that she turned him down, that he pursued her to Flanders and that he dragged her from her horse by her braided hair to persuade her to marry him is definitely not. William of Malmesbury, a monk who chronicled the times, says her obedience to her husband and fruitfulness in children, excited in his mind the tenderest regard for her, which is a distinctly monkish view of the blossoming of love. It clearly was a loving relationship, however, and he adds that, when she died, William, weeping most profusely for many days showed how keenly he felt her loss.

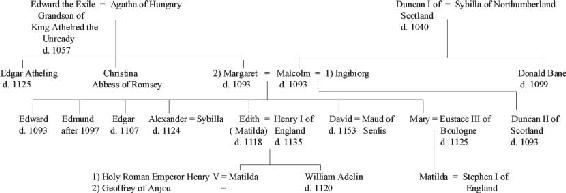

Fruitful, too, is a good description of the marriage. Four sons and at least five daughters were produced by William and Matilda over a period of about eighteen years, and though some are rather shadowy figures, a good number appear as strongly defined characters. Robert was the eldest son, born either in 1051 or 1054 depending on which account of the marriage is believed. He was probably followed by a daughter, Adeliza, who may be the one some Norman accounts declare was to marry Harold Godwinson, though she could only have been around twelve years old at the time. The next few years saw the arrival of Richard, William, Cecilia, Constance and possibly Matilda. Then there was something of a gap before the birth of Adela, around 1067, and Henry in 1068.