T he late Dr Jeremy Catto, for many decades history fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, was an outstanding Oxford personality whose polished methods, almost imperceptible in their operation, reached throughout the globe suaviter in modo, fortiter in re. I am deeply grateful for his unstinting encouragement in writing this book and to Professor David Parrott of New College, who so kindly read a large part of it and whose wise advice was so invaluable. All errors are, of course, exclusively mine.

I am also very grateful for the inexhaustibly patient and professional support of Lord Strathcarron and his team at Unicorn Publishing and my editor, Elisabeth Ingles. The staff at the British Library and the London Library, particularly during the tiresome tribulations of the lockdown, have been beyond praise. Both have extraordinary resources but the treasures of the latter which so often emerge unexpectedly from the most unsuspected corners of the collection never cease to amaze. I am grateful to the Royal Collections in The Hague, courtesy H.M. The Queen of the Netherlands, for their help. My thanks too to Heather Holden-Brown for her introduction to Ian Strathcarron.

The book is dedicated to all those jolly dogs from Oriel College with whom I have so often heard the chimes of midnight.

But only in the second degree.

My wife, Andrea, occupies the first place, whose When will it be finished? ensured that it was.

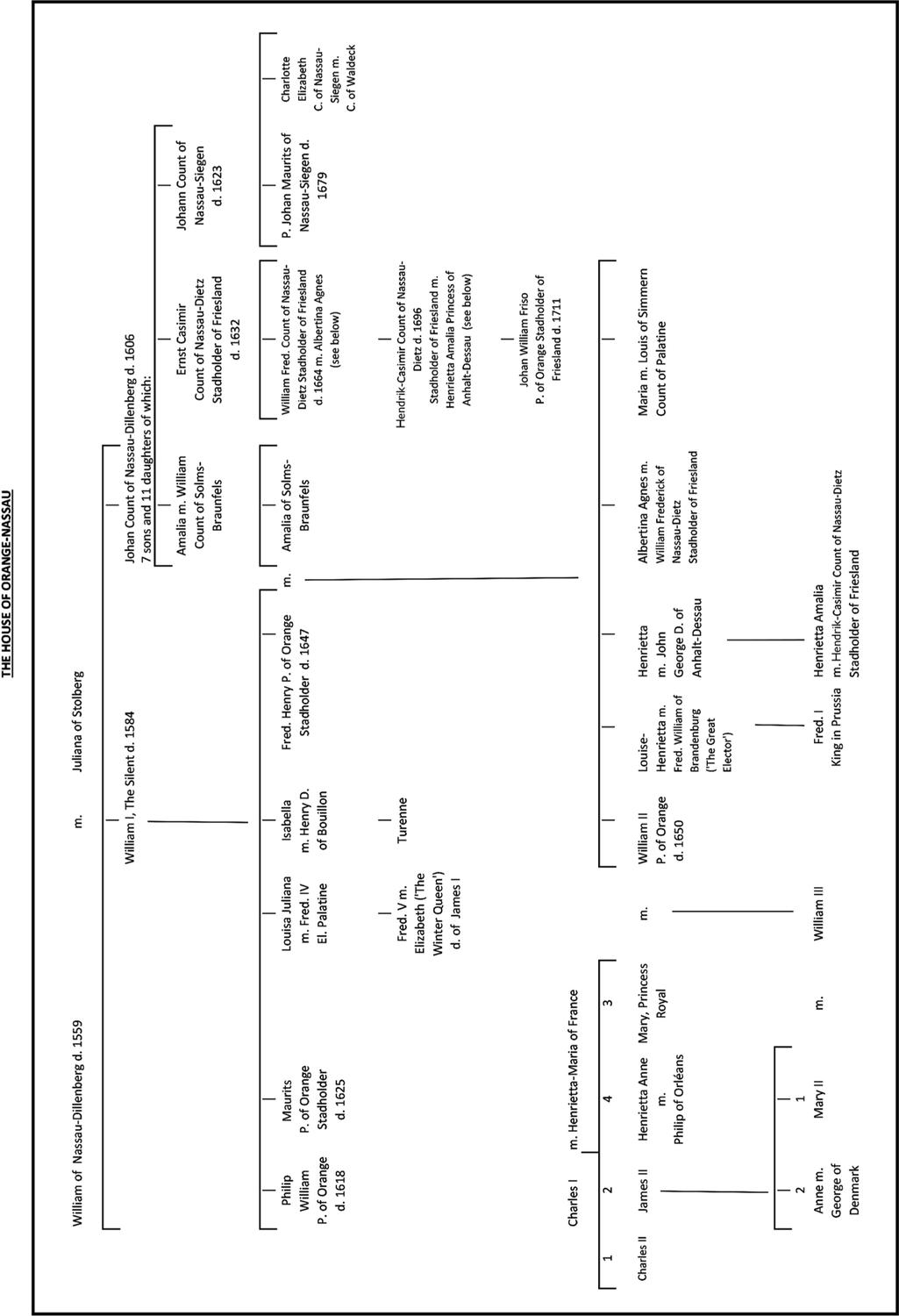

W illiam III was so called not only because he was the third Prince of Orange of that name, but also because he was the third king named William to accede to the throne of England. Although he invaded England from the Dutch Republic, he was neither Dutch nor English, but a cosmopolitan European aristocrat. His familys origins did not lie in the Principality of Orange, which William never visited, which was situated far away in the south of France, and which was tiny and insignificant in every way, save for one supremely important and overriding attribute it conferred sovereignty. The Princes of Orange were independent sovereign princes.

Where their origins did lie was in Germany, and the clan never lost touch with their German roots.

They acquired largely through marriage considerable wealth in the Low Countries and the other lands that the dukes of Burgundy governed; by this means and through their prestige as sovereign princes, the clan acquired formidable powers of patronage and an extensive client system in the Netherlands and Germany. Through the marriage of Williams father, William II of Orange, to Mary, the daughter of King Charles I, this was extended into England.

The clans system could be put at the disposal of the Dutch political class when the Low Countries rebelled against the Habsburg successors of the dukes of Burgundy and established their independence in the Dutch Republic after a war lasting 80 years. It could also be put at the disposal of the English political class when they turned against King James II in 1688.

A number of books have been written about William III, but this one deals with his career before he became King of England; it examines in detail how his patron/client relationships worked across the European scene and explores the inevitable conflict that arose with the rival system of King Louis XIV of France.

H e did not know that he was dying as the waters lapped against the yacht that was carrying him through the river and canal systems of the United Provinces to The Hague. The day before he had been hunting at his country house at Dieren, near Arnhem, returning with a fever. But a couple of days after his arrival at his quarters at the Binnenhof at The Hague the rash that had broken out over his body was recognised as smallpox. On Sunday 6 November 1650, at about 9 oclock in the evening, Prince William II of Orange died.

In the same quarters, in the evening of Monday 14 November, between 8 and 9 oclock, his son, William III, was born.

It was the birthday of his mother, Mary, who was 19 years old.

William IIIs family of Orange-Nassau derives its origins from the hilly country of Nassau in Germany, through whose territory there flows the pleasant Lahn river, which joins the Rhine just south of Coblenz; and in the surrounding areas the little towns of Dillenburg, of Siegen and of Dietz provided the different branches of the family with distinguishing suffixes to add to the Nassau name. By the second half of the 12th century the counts of Nassau had acquired a modest significance, accompanying the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, on his wars in Italy, in the Holy Land, and in Germany itself. Their aims were those of their military caste, to gain reputation, to increase their status, and to extend their territorial possessions. But, until the latter end of the Middle Ages, they remained on a middling footing.

What raised them from the position of run-of-the-mill German counts were shrewd marriages and the skilful exploitation of relations with the powerful dynasties of their day. In 1403 one of them married an heiress, the great-niece of a banker who had financed the princes and rulers of the Netherlands, and whose political influence had become as extensive as his fortune. The Nassaus were solidly established in the Netherlands, a position, as the Dutch royal family, they have retained to this day.

Making use of these firm foundations, they developed ties, which, despite some setbacks, became ever closer, with the dukes of Burgundy, a cadet branch of the French royal family, who had in the 15th century become the major power in the Low Countries.