Contents

Guide

Page List

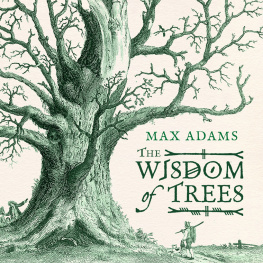

Trees

of Life

MAX ADAMS

The Dark Hedges, an avenue of beech trees in Ballymoney, Northern Ireland

This is an Apollo book, first published in the UK in 2019 by Head of Zeus Ltd

Copyright 2019 Max Adams

The moral right of Max Adams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN [ HB ] 9781789541427

ISBN [ E ] 9781789541410

Version 1.1

Head of Zeus Ltd

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

www.headofzeus.com

Contents

CHAPTER 1

Cork, Rubber, Mulberry: a cornucopia 11

CHAPTER 2

Dragons Blood and Jesuits Bark: trees for dyes, perfumes and medicine 57

CHAPTER 3

From Apple to Walnut: the fruit and nut bearers 97

CHAPTER 4

Sugar and Spice: a cooks bounty 139

CHAPTER 5

Supertrees 185

CHAPTER 6

Trees for the planet 229

Introduction

Camille Pissarro, Le Verger (The Orchard) 1872.

What is a tree of life? What makes a tree useful? The short answer is that all trees are life-giving; all are useful. Trees, like the oceans, drive the earths climate and its incomparable biodiversity, absorbing carbon dioxide, pollutants and the energy of sunlight and giving out oxygen. Trees cycle water and gaseous nitrogen, act as air conditioners and provide habitats for millions of species of other plants, insects, birds, mammals and amphibians. They stabilize and enrich soils, slow down floods.

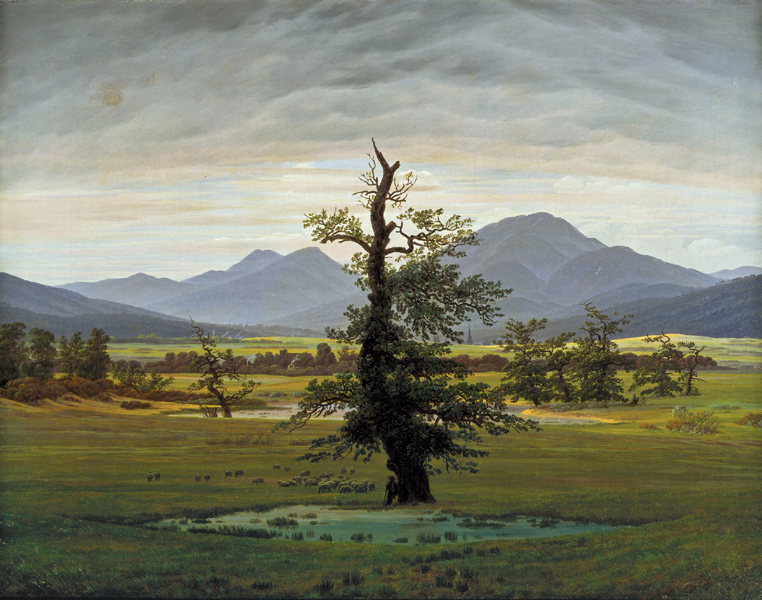

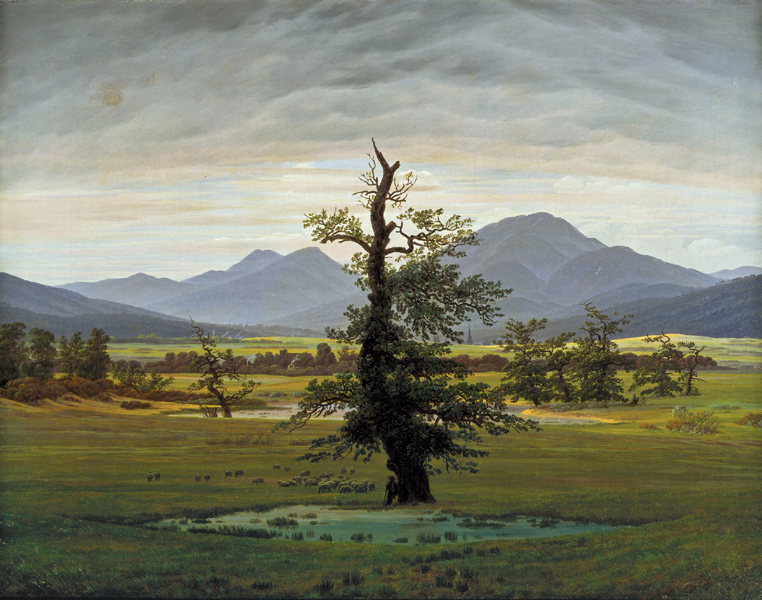

A single veteran tree standing in a field may host more than 300 species of birds and insects. Exploiting it for food, they also use it as a place to nest and reproduce, take refuge from predators in the cracks and fissures of its bark, or as a perch from which to advertise their wares to potential mates. Trees forming a continuous canopy as woods or forests create biomes on a grander scale, sometimes spanning nations and continents as a huge living organism of almost infinite interlocking and interdependent biological and behavioural relationships. When trees die their materials are recycled or act as carbon sinks.

For early humans, an intelligent species foraging in the savannah forests of East Africa and highly dependent on trees, they have been partners in a great cultural adventure. Trees provide shelter and shade as well as materials for constructing the most elemental and elegant tools and building shelters. We eat their fruit, use their leaves, bark and roots for medicines; their wood fuelled the fires that liberated us as a thinking, creative species. Trees have colonized every continent that supports permanent human communities; they, like us, are adaptable and resourceful. At least 60,000 species have evolved during the last 300 million years, brilliantly responding to every opportunity and threat that nature offers.

Trees beauty, adaptability and resilience, their longevity and apparent stoicism have also inspired humans. The role of trees in connecting the heavens and the earth, life and death in ever-renewing cycles can seem almost magical. Mythology makes much of their supposed wisdom, their supernatural abilities and their propensity to host living spirits. Artists and writers have eulogized, anthropomorphized, satirized and observed trees over millennia. As botanists and biologists study the miraculous workings of trees they seem to become more, not less, marvellous and complex. We know that trees can communicate with each other above and below ground; that they can draw up water from the soil to improbable heights; that they effortlessly and routinely create solid matter from light, gas and water; that they have found all manner of means to reproduce at a distance with immovable potential partners.

Caspar David Friedrich, Der einsame Baum (The Lonely Tree), 1822.

Humans are restless, curious, empirical experimenters with nature. From the first use of a sharp tool to split a log or peel bark, communities have explored and exploited trees over the best part of a million years. In every habitable region of the planet intimate practical knowledge of their uses, materials, propagation and behaviour has been accumulated and passed on to new generations. In the Caribbean young children and visitors are warned not to shelter from rain beneath the poisonous manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella) for fear of horrible blisters, and never to eat its promising-looking fruit. The herders of the Altai mountains in Kazakhstan long since learned to trust their pigs and horses to find the sweetest varieties of wild apples. In Southeast Asia the knowledge that certain trees, when damaged, exude a mouldable and waterproof milky-white substance was acquired thousands of years ago. The memory of the genius who first dried and roasted the bean of the cacao tree of the Andes to taste the food of the gods is lost in the mists of time.

In this book I celebrate the richness of our relationship with trees, woods and forests in a series of portraits of those trees that have spawned particularly interesting relations with human communities. In many cases these are stories of deep local knowledge followed by global discovery, exploitation, environmental fallout and social oppression. In others, obscure and unprepossessing trees have turned out to hold potential solutions to the challenges of modern life through their medicinal properties or their status as keystones in subsistence strategies for some of the worlds poorest communities. Where possible, I have illustrated the stories with fine photography or with paintings by great artists or botanical illustrators.

Individual species have, quite naturally, found themselves fitting into a number of themes. In the I look at those trees that have yielded materials of great practical value from timber with a huge range of handy characteristics to bark for paper and rope, nuts for lighting and seed cases for percussion instruments. I devote a chapter to the edible fruits and nuts, some better known than others; another to trees that have given us special culinary ingredients and traditions. Dyes, essences and medicines are the focus of a dozen or so tree profiles, while a whole section is devoted to what I call trees for the planet species so valuable to all humanity that they must be protected from loss by neglect or ignorance. I have also chosen a select few species for a chapter called Supertrees a bakers dozen of arboreal A-listers that punch far above their weight. Some trees might have sat comfortably in other chapters but I hope that, as a whole, my choices a very small selection out of thousands of useful species will encourage readers to learn more about these givers of life on which we rely so much and about the communities who value and protect these natural riches under our care.