www.headofzeus.com

To lifelong learners everywhere

Contents

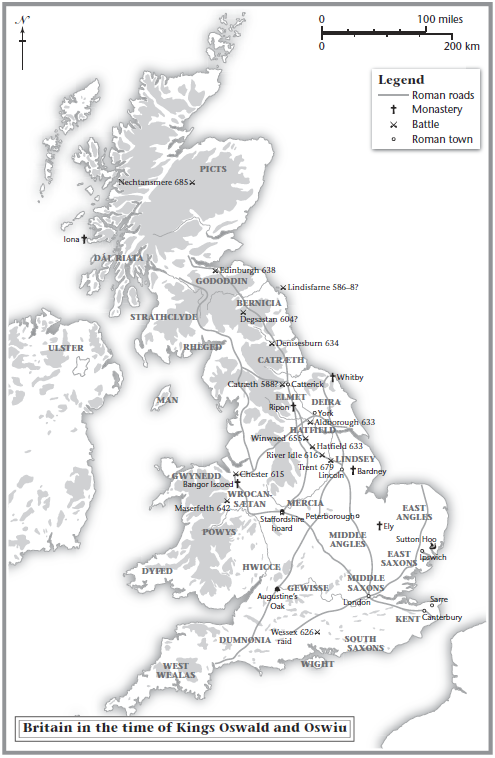

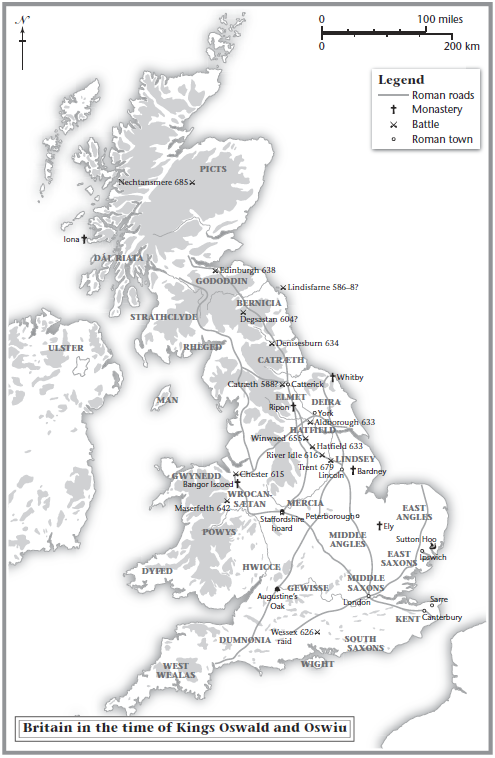

Britain in the time of Kings Oswald and Oswiu

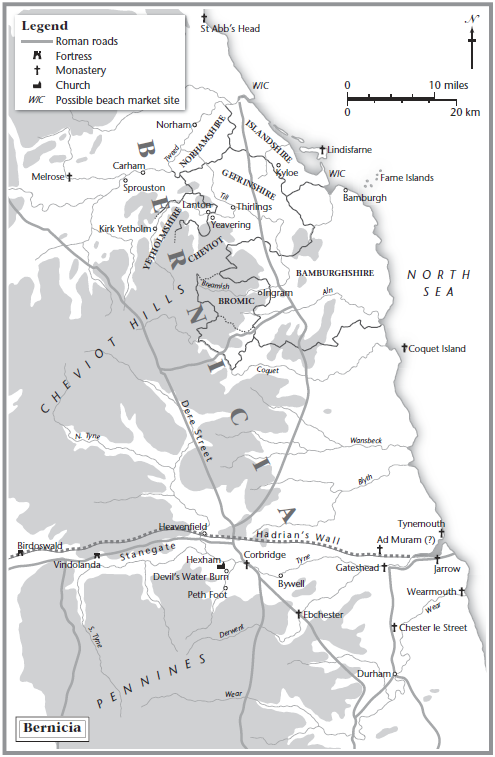

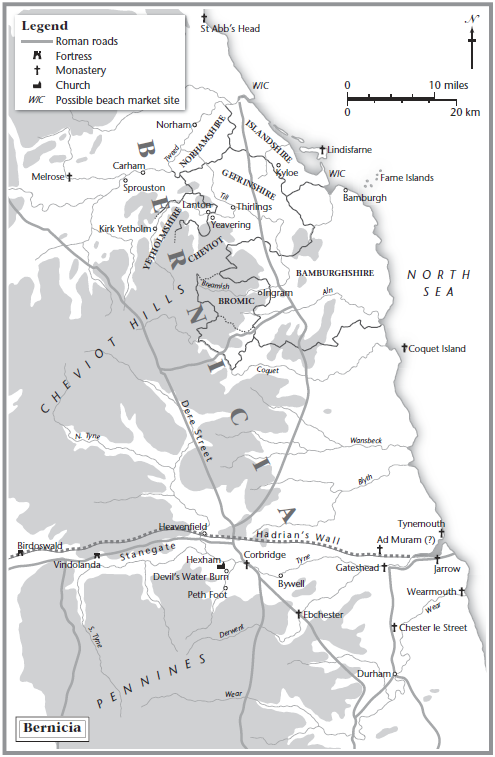

Bernicia in the time of King Oswald

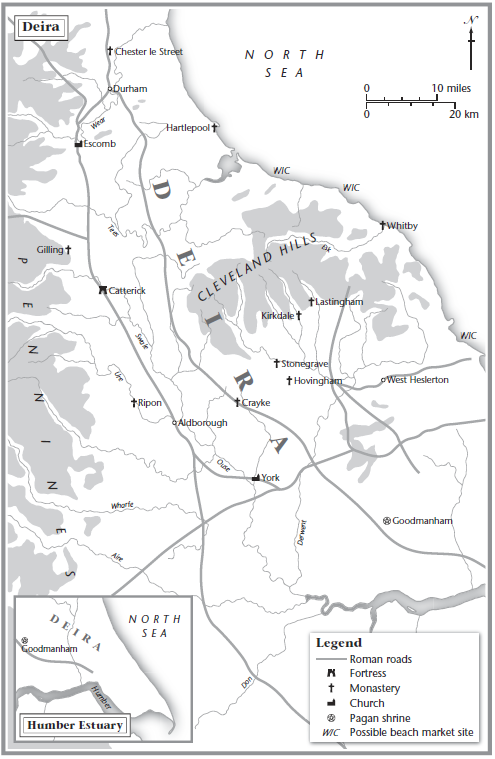

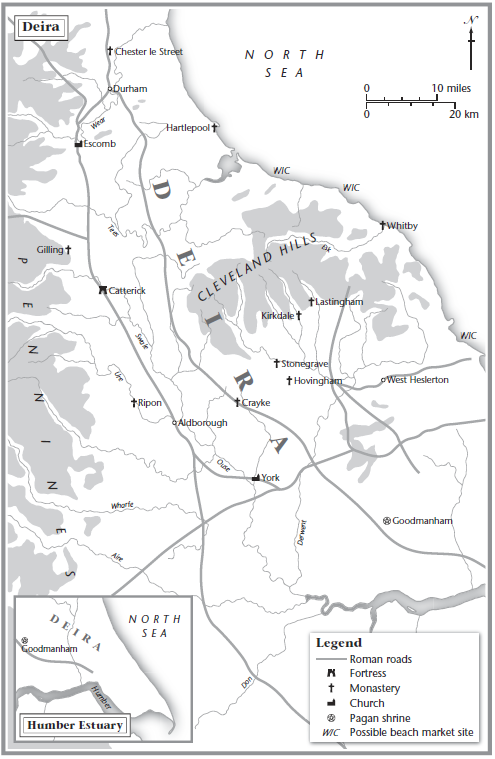

Deira in the time of King Oswald

The timelines I have compiled to give readers some idea of a continuous chronological narrative cannot really be reliable. The numbers will never add up because there is simply not enough accurate information to be precise about individual years. No king ever reigned for an exact number of years, so there is immediately an element of smoothing over the cracks when it comes to interpreting regnal lists. Death dates are usually more accurate than birth dates because people remembered when a famous person died whereas newborn babies were rarely famous enough for the date to matter. But even death dates were subject to political manipulation and scribal error.

Bede was a pioneer of accurate dating; he did his very best to iron out the contradictions between dates calculated from regnal lists and those from entries in Easter annals, which computed dates for the celebration of Easter and often added significant or memorable events in a side column. The Nennian Chronology (known as the Annales Cambriae or Welsh Annals), which survives in a famous manuscript called, with typical academic dryness, Harleian 3859, must have been drawn from such an annal. Just how many of the entries were contemporary and how many were interpolated by later copyists is a much-debated point.

Then there is the problem of when years began and ended. No-one can quite agree when Bede considered the year to begin and end; so, for example, the Synod of Whitby is recorded as having taken place in ad 664; but it may belong to autumn of the year before, if Bede was using the Roman civil year from September to September in his calculations.

Great care also has to be taken in trying to match Bede, Nennius and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A great deal of superb scholarship has been applied to working out which of these major sources for the Early Medieval period borrows from which other sources and, by implication, whether any of them borrowed from lost annals which can in part be reconstructedas it can in Ireland, where most of the chronicles derived from a lost Ionan source which can be reconstructed with some confidence.

Reconciling dates from various annals has provided doctoral theses for generations of students and much progress has been made in rationalising some of the dating systemsfor example, the Annales Cambriae seem to more or less consistently date events three years too early; and I will show in Appendix A how fraught are the dates of the earliest Bernician kings. In the end, one either accepts that the problem is insoluble or does ones best with all the caveats that come with educated guesses. One thing is for sure: after the year 616 or 617, when thelfrith is defeated at the Battle on the River Idle by Edwin, dates become much more reliable. It is a great tribute to Bede to say that after his death Northumbrian chronology steadily declines to the point where a hundred years or so later it is impossible to write a continuous narrative of Britain north of the Humber. Without dates, history is lost. Without the Christian church, and writing, there were no dates.

I

Queens move

So bi swilost...

and gomol snoterost

Truth is the clearest thing...

and the old man

is the wisest

The dark ages are obscure but they were not weird. Magicians there were, to be sure, and miracles. In the flickering firelight of the winters hearth, mead songs were sung of dragons and ring-givers, of fell deeds and famine, of portents and vengeful gods. Strange omens in the sky were thought to foretell evil times. But in a world where the fates seemed to govern by whimsy and caprice, belief in sympathetic magic, superstition and making offerings to spirits was not much more irrational than believing in paper money: trust is an expedient currency. There were charms to ward off dwarfs, water-elf disease and swarms of bees; farmers recited spells against cattle thieves and women knew of potions to make men moreor lessvirile. Soothsayers, poets, and those who remembered the genealogies of kings were held in high regard. The past was an immense source of wonder and inspiration, of fear and foretelling.

Historians, bards and storytellers alike were tempted to improve on the truth, as they are today. But you can forget pale hands emerging from the depths of lakes offering swords of destiny to passers-by. You can forget holy grails and messianic bloodlines. Bloodlines mattered as political reality, it is true, but they were traced from the ancestral tribal gods of Britain and Germany or the last generals of the Roman Empire, not from the crucified prophet of Nazareth.

One of The Wonders of Britain, from a list written down at the beginning of the ninth century but surely recited to children and kings for hundreds of years before and after, was an ash tree that grew on the banks of the River Wye and which was said to bear apples. In 1993 one was found growing on cliffs in the Wye Valley in Wales. Early Medieval Britain was full of such eccentricitiesthe Severn tidal bore and the hot springs of Bath fascinated just as they do nowbut the people who survived the age were, above all, pragmatists and keen observers of their world. Their knowledge of weather and season, wildflower and mammal, shames the modern native. They were consummate carpenters, builders and sailors. The monk Bede, writing in the year 731, knew that the Earth was round, that seasons changed with latitude and that tides swung with the moons phases.

Love and romance must have played their part in life, although few men writing during the three hundred years after the end of Roman Britain thought to mention them. For the most part life was about getting by, about small victories and the stresses of fretting through the long nights of winter, about successful harvests and healthy children.

The vast majority of people in the Early Medieval British Isles, as across Europe, are invisible to us. We know farmers and craftsmen existed: we have their tools and the remains of their fields. Sometimes their houses can be located and reconstructed; rather more often we find their graves. Very, very rarely we hear their names. Sometimes they encountered seafarers and travellers from strange lands who brought tales of exotic beasts and holy places. The countryside was busy with people, nearly all of them to be found working outside in their fields or woods, or fixing something in their yards; ploughing, milking, weeding, felling, threshing and mending according to the season. We have their languages: the inflexions, word-lore and rhymes of Early English, Old Welsh, Gaelic and Latin tell us much about their mental worlds. We can guess at numbers: somewhere between two and four million people living in a land which now holds fifteen to thirty times that many. Their history is recorded in our surnames and in the names of villages and hamlets. With care, their landscapes can be reconstructed and at least partly understood. The hills, rivers, coasts, some of the woods and many of their roads and boundaries can still be walked, or traced on maps. And through pale dank sea-frets of late autumn King Oswalds Holy Island of Lindisfarne still looms mysteriously across the tidal sands of Northumberlands wave-torn coast.

Next page