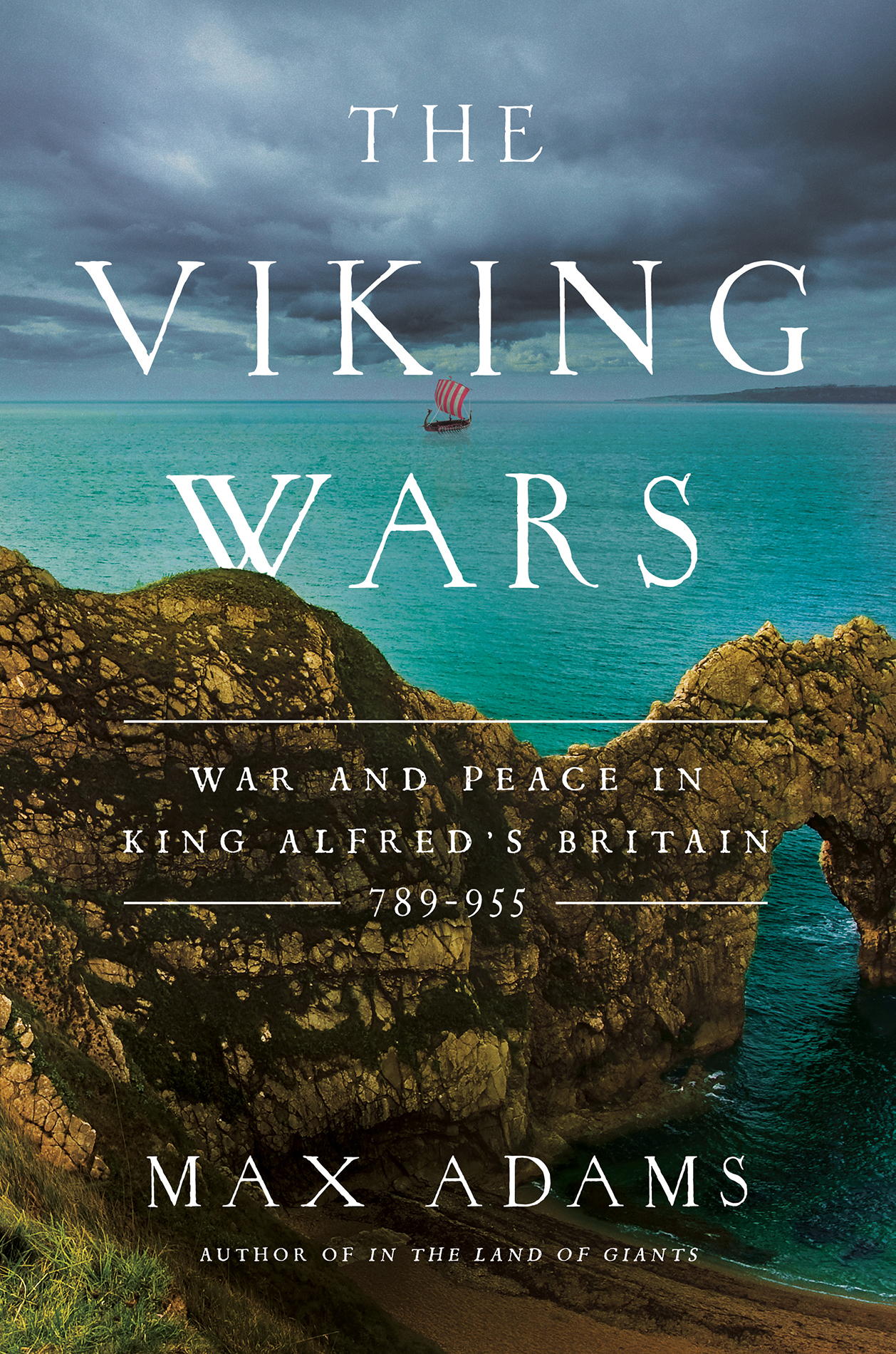

THE

VIKING

WARS

WAR AND PEACE IN

KING ALFREDS BRITAIN

________789955___________

MAX ADAMS

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

Original sources and the editions used in the text and timelines:

AASB Acts of the abbots of St Bertin by Folcwin. EHD Secular narrative sources 26, Whitelock 1979.

AC The Annales Cambriae. Morris 1980.

AClon - Annals of Clonmacnoise. https://www.ucc.ie/celt/transpage. html

elweard Chronicon. Campbell 1962.

AFM Annals of the Four Masters. https://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/ T100005A

Alcuin Ep The epistolae of Alcuin. Allott 1974.

APF - Armes Prydein Fawr. Isaac 2007. ASB The Annals of St Bertin. Nelson 1991.

ASC - Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Garmonsway 1972.

Asser Life of King Alfred. Keynes and Lapidge 1983.

AU Annals of Ulster, http://www.ucc. ie/celt/online/100001A.

CKA Chronicle of the Kings of Alba. Woolf 2007.

Egils Saga Scudder and skarsdttir 2004.

EHD English Historical Documents volumeI. Whitelock 1979.

FoW Florence of Worcester : the reigns of the Danish kings of England. EHD Secular narrative sources 9. Whitelock 1979.

Fragmentary Annals Wainright 1975b. Gesta Regum Anglorum William of Malmesbury. Giles 1847 and EHD Secular narrative sources 8. Whitelock 1979.

HE - Bedes Historia Ecclesiastica. Colgrave and Mynors 1969.

Historia Abbatum Webb and Farmer 1983.

HR Historia Regum. EHD Secular narrative sources 3. Whitelock 1979.

HSC Historia de Sancto Cuthberto. South 2002.

LDE Symeons Libellus de Exordio. Stephenson 1993.

Liber Eliensis Fairweather 2005.

Nithards Histories Scholz 1972. Orkneyinga Saga Plsson and Edwards 1981.

Poetic Edda Larrington 2014.

Prose Edda Bycock 2005.

RFA Royal Frankish Annals. Scholz 1972.

RoW Roger of Wendover: Flores Historiarum. Giles 1849.

VC Vita Colombae. Adomnins Life of St Columba. Sharpe 1995.

VW Eddius Stephanuss Vita Wilfridi. Webb and Farmer 1983.

Charters are referenced by their S-(Sawyer) number, which can be used to search for them in the online resource called the Electronic Sawyer: http://www.esawyer.org.uk/about/index.html.

THERE IS NOW an overwhelming amount of literature on the Viking Age in Britain. In acknowledging the debt I owe to all those scholars on whose work I have leant, I apologize for any errors of interpretation or fact. Any omission of credit on my part is inadvertent. I am grateful to Professor Sam Turner of the University of Newcastle Department of History, Classics and Archaeology, for affording me invaluable research facilities as a Visiting Fellow. I would particularly like to thank the following for their help or advice along the way: Werner Karrasch, the brilliant photographer at Roskilde Ship Museum; my cousin Anya, who introduced us; my old friend Jacqui Mulville; colleagues and friends in the Bernician Studies Group; Professor Diana Whaley for all sorts of help with language and place names; Peter Fitzgerald, for kindly showing me Ecgberhts stone in Penselwood; and Paul Blinkhorn for acting as a ceramic fact-checker. My thanks also go to Dr Lynne Ballew for reading the text and making many invaluable suggestions for improving it. My editor, Richard Milbank, has been unfailingly encouraging, sympathetic and sharp-eyed. A book is only half a book until it has been through its publishers hands. The designers and production staff at Head of Zeus are similarly owed a great debt of gratitude for bringing lfreds Britain to life with style. Finally, a thank you to the diggers: the archaeologists who tough it out in the field, who give us hope of drawing back the veil that hides our ancestors from us.

ALSO BY MAX ADAMS

In the Land of Giants

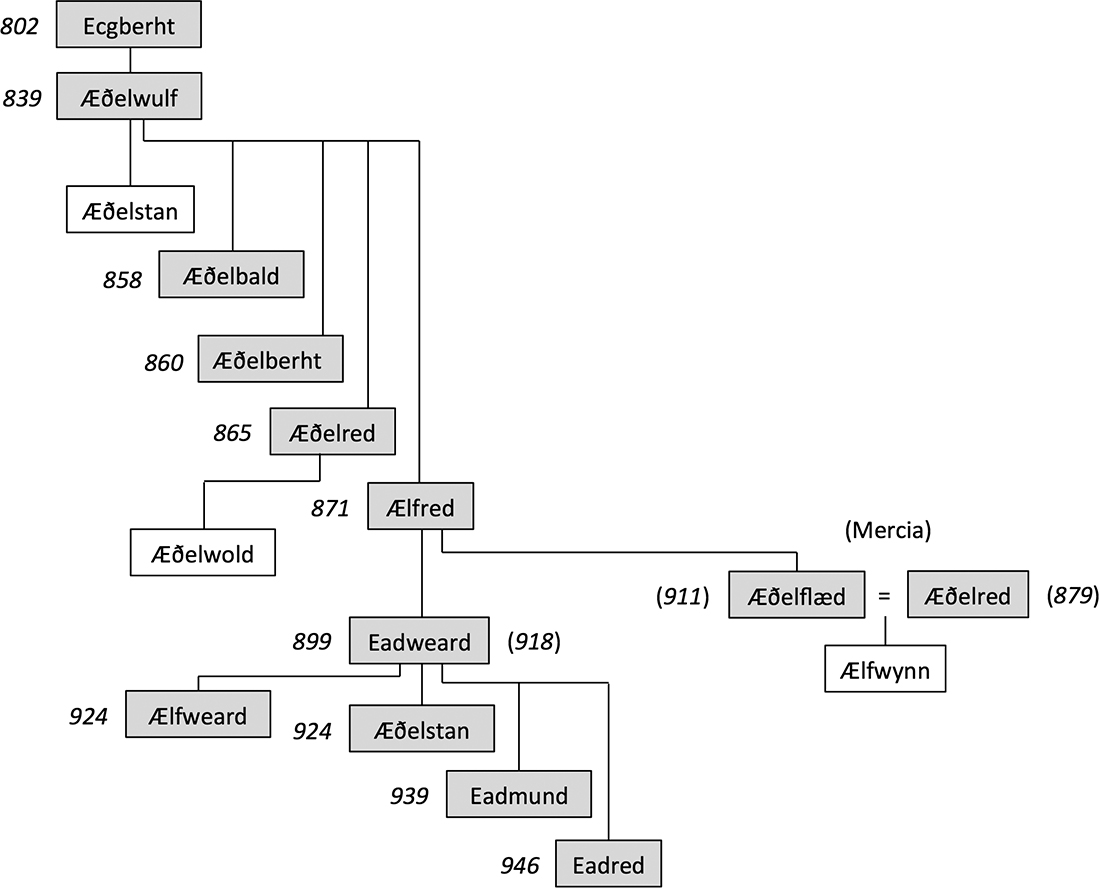

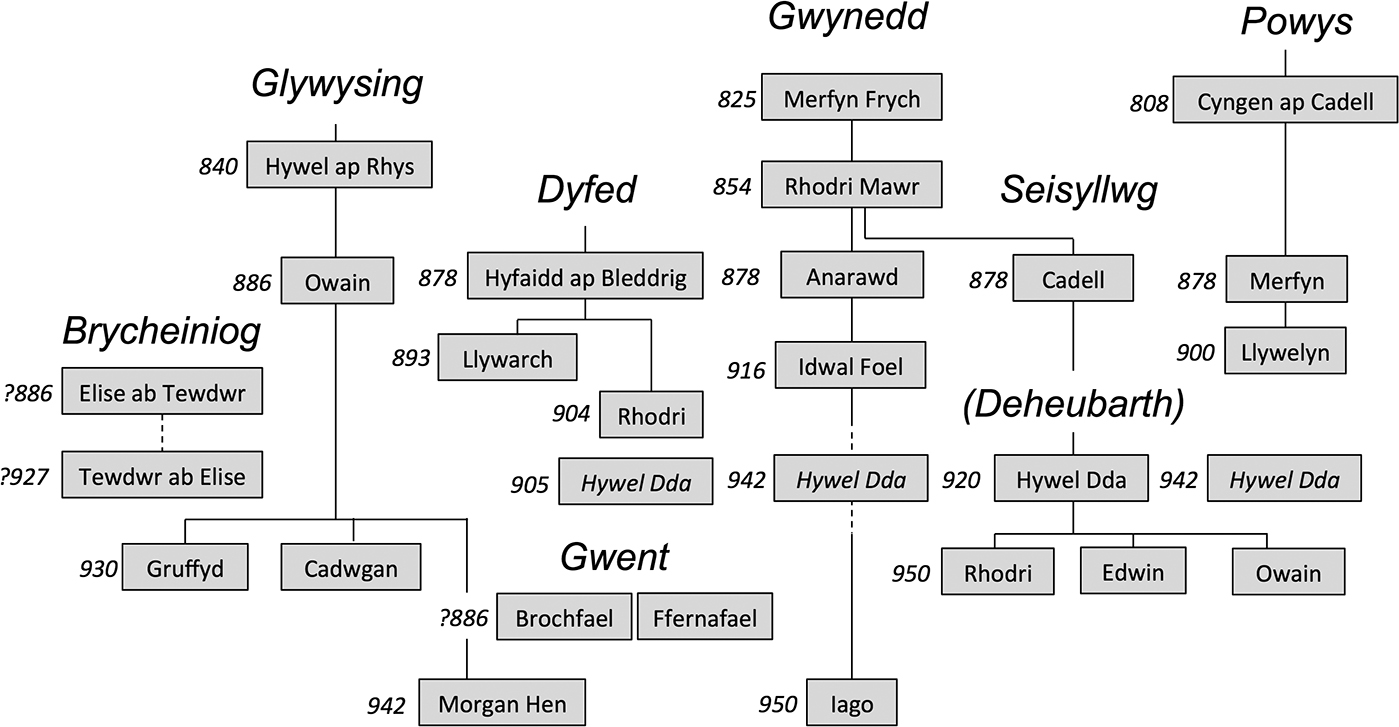

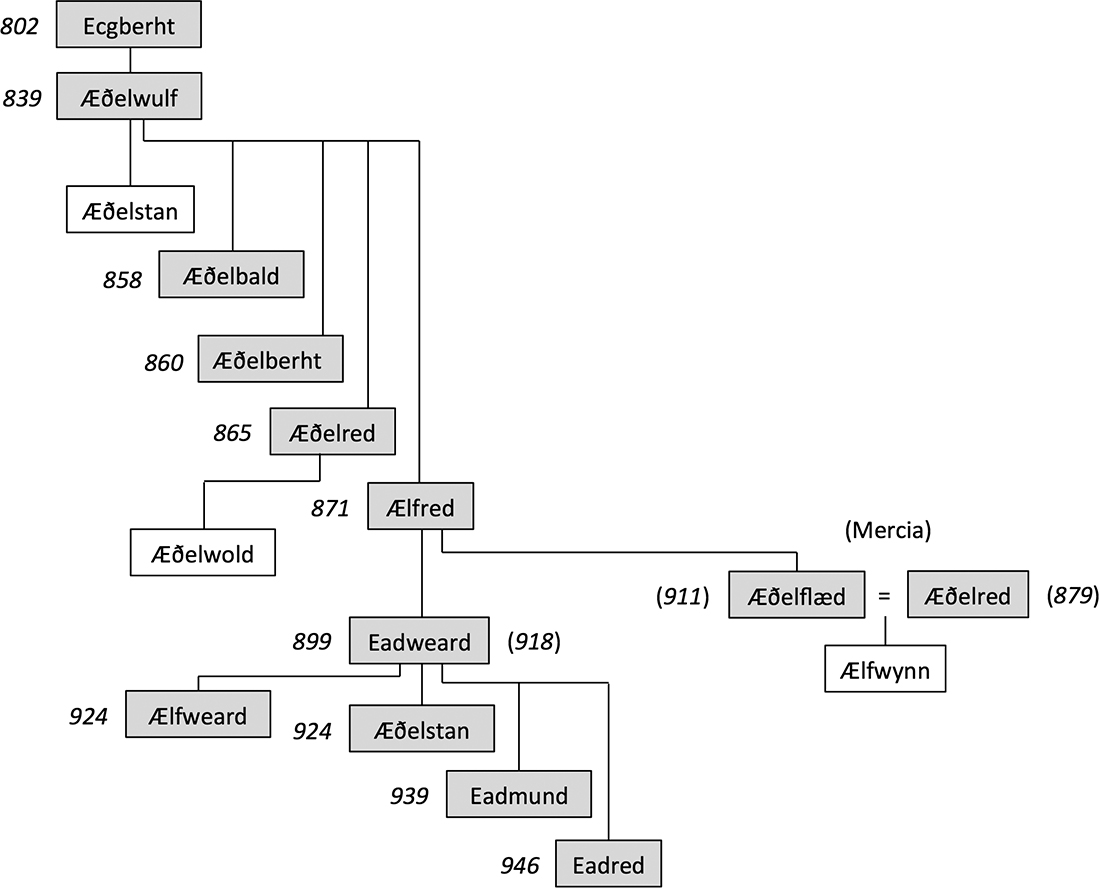

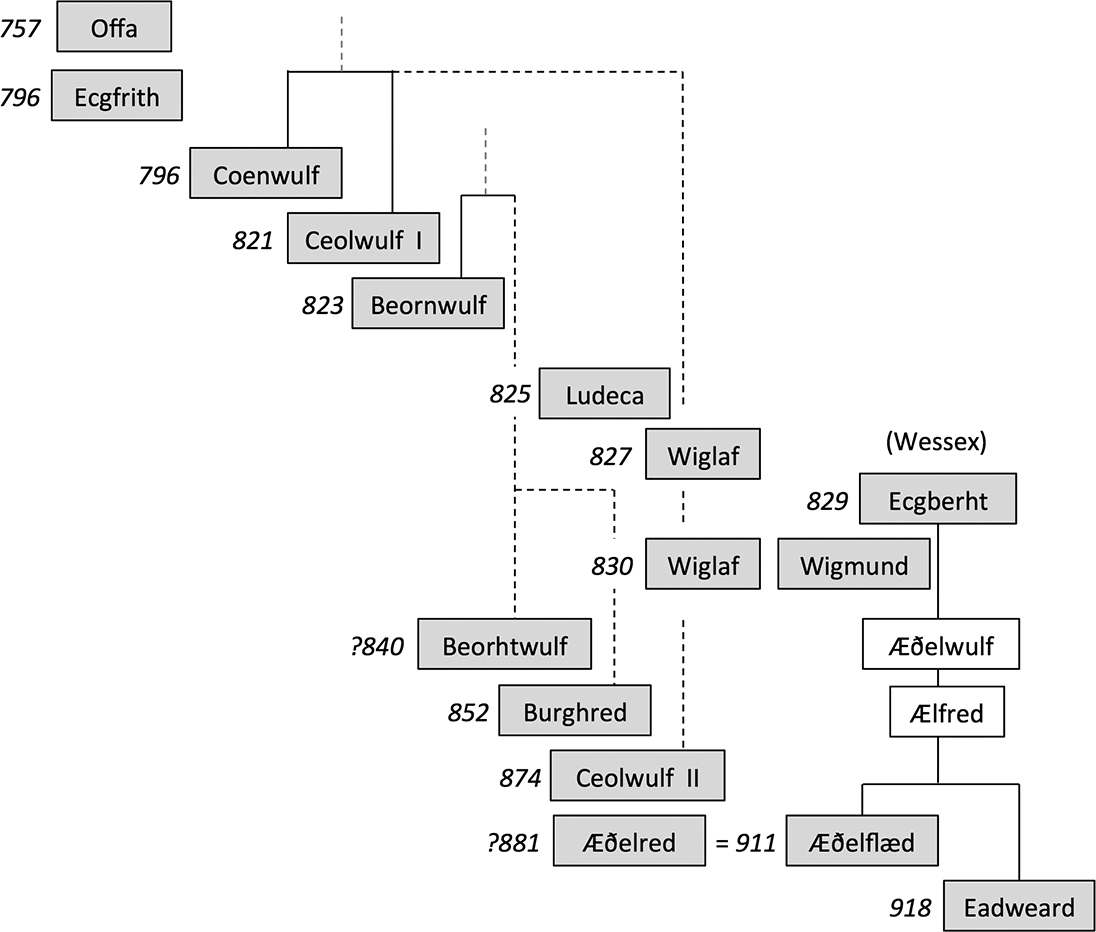

802955

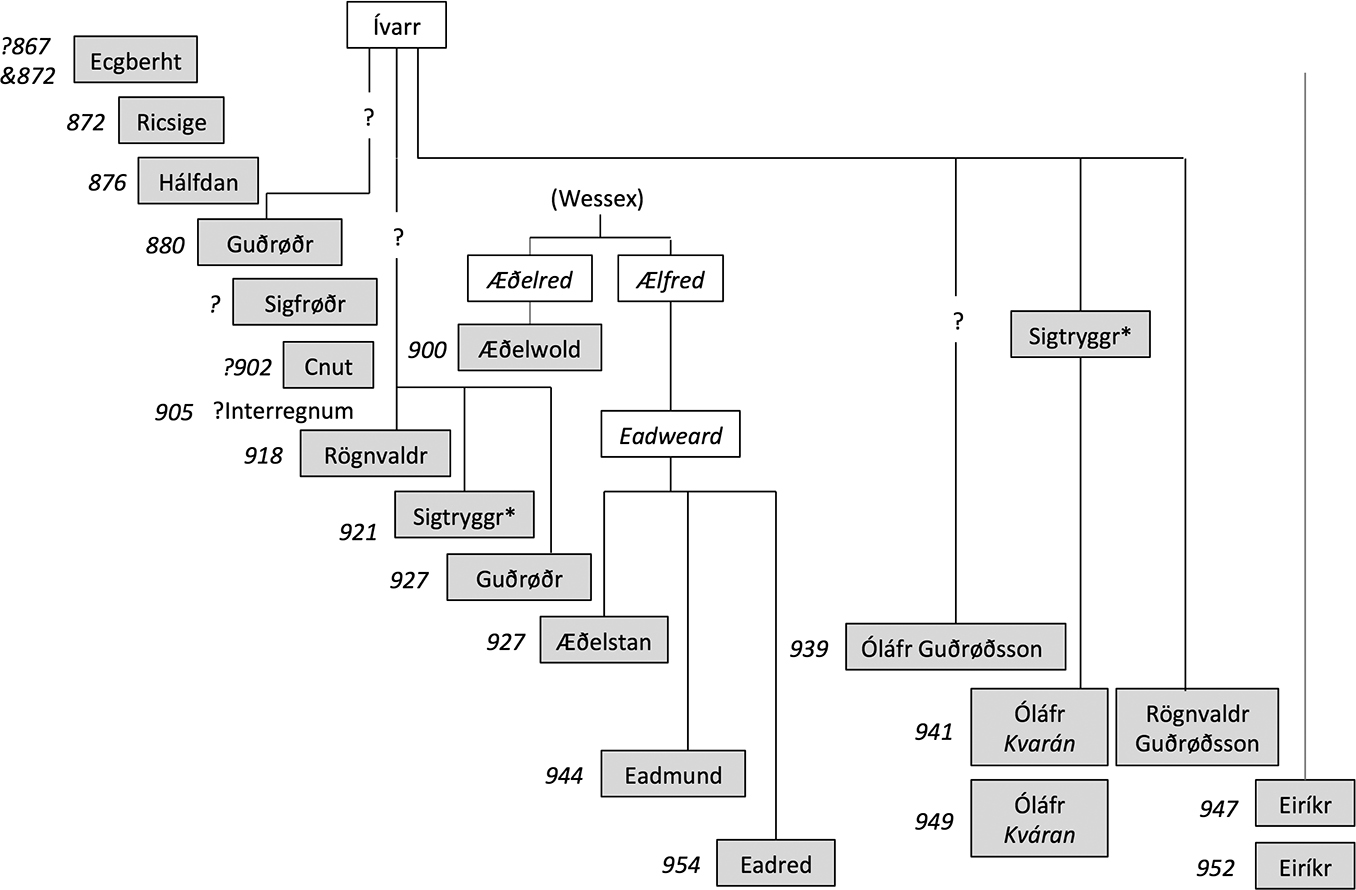

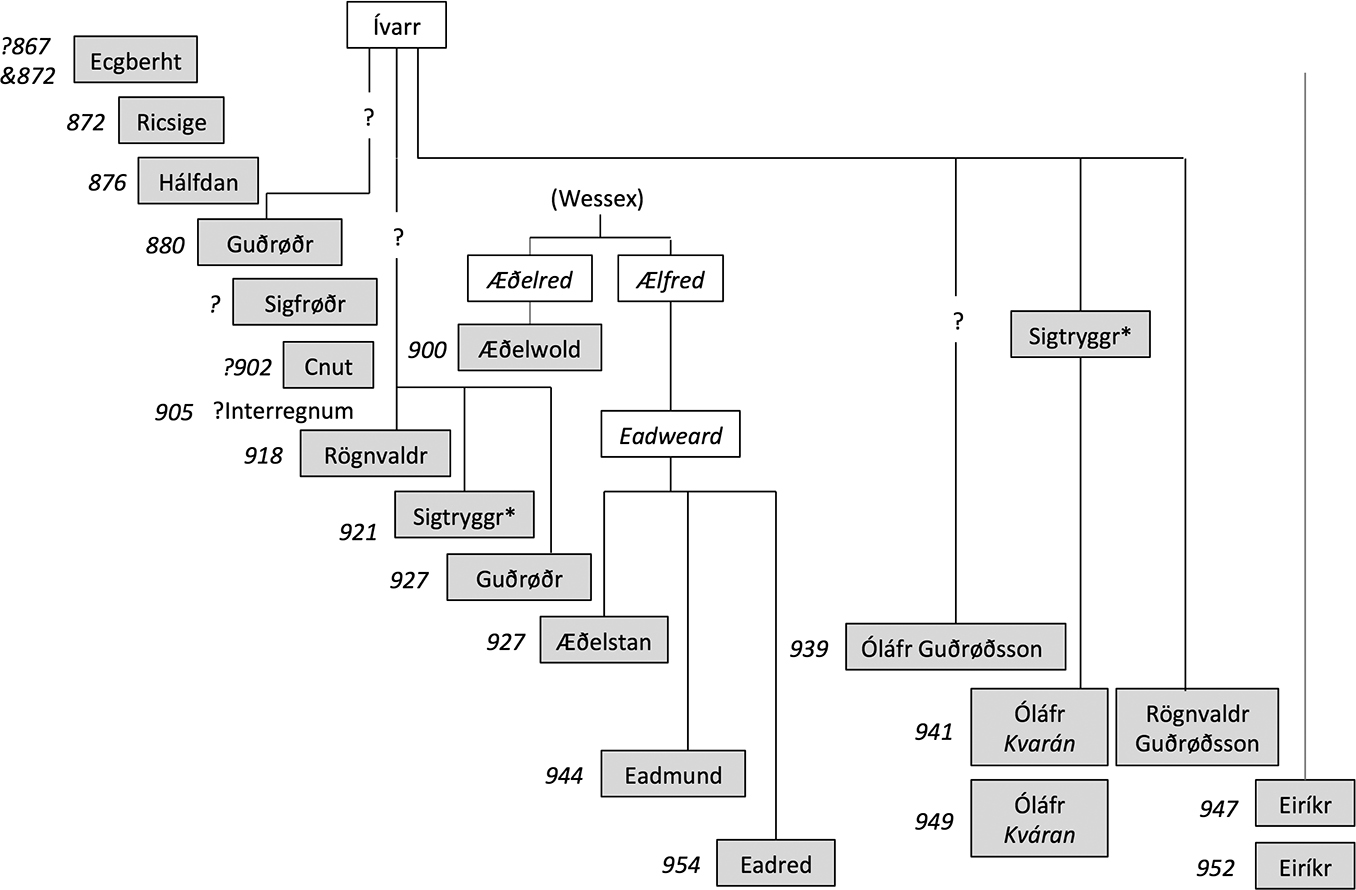

867955

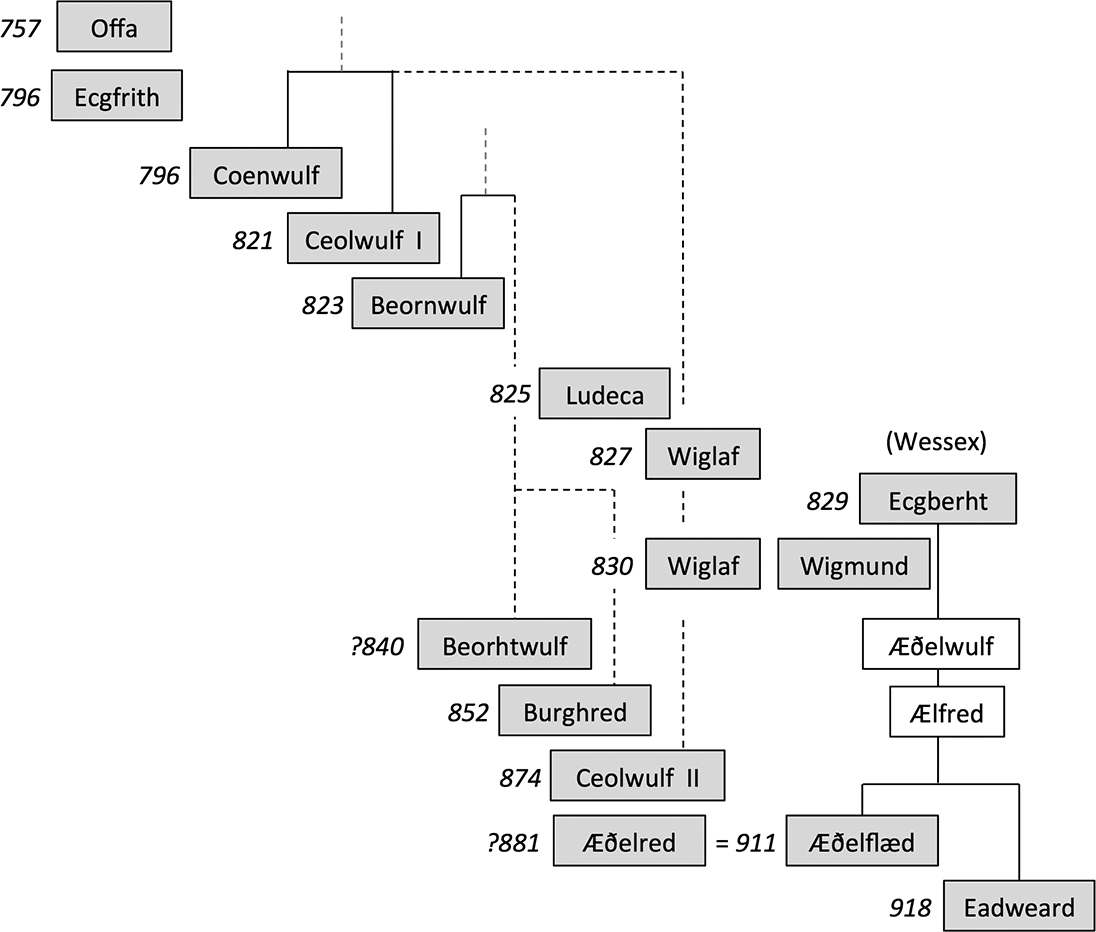

757924

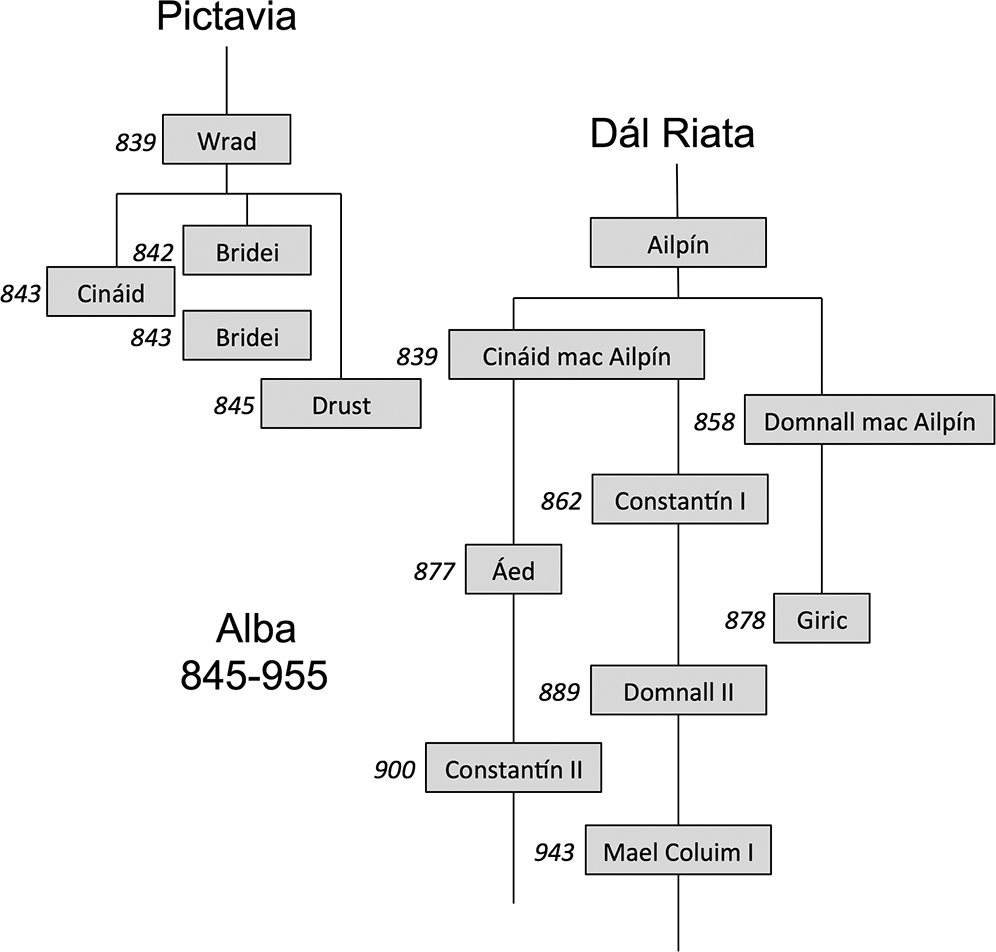

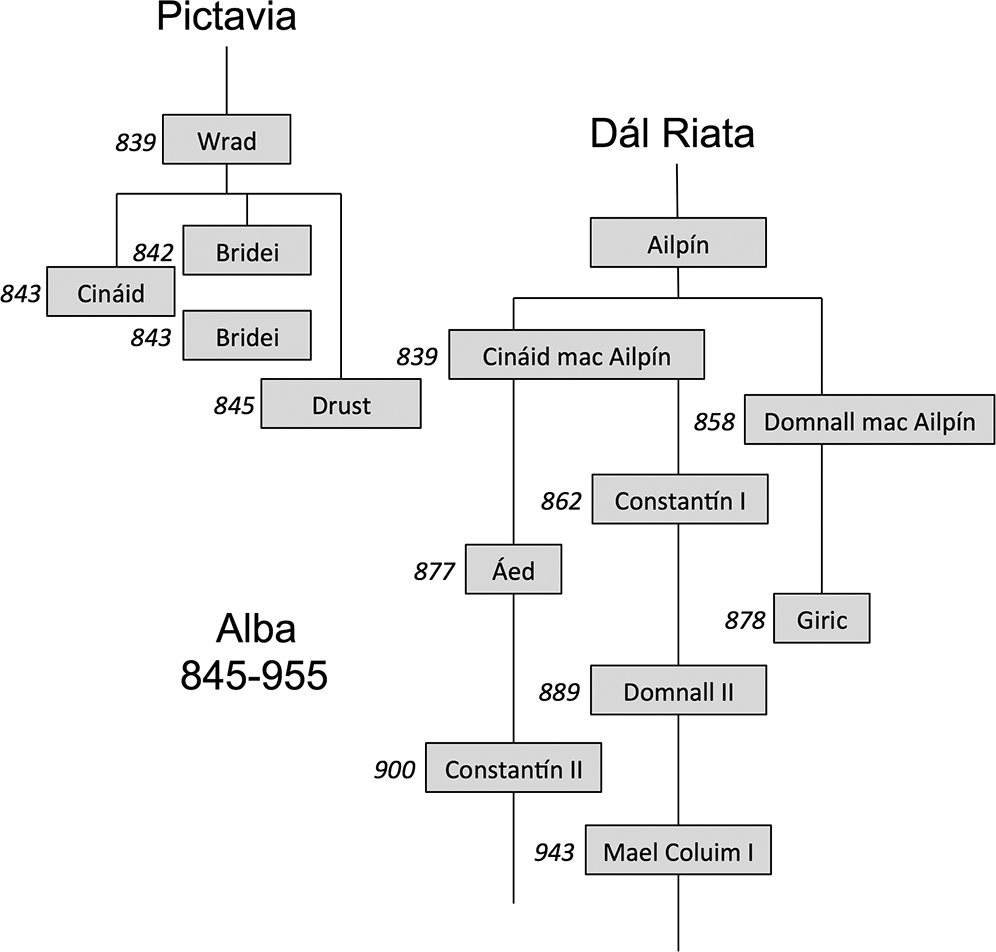

839955

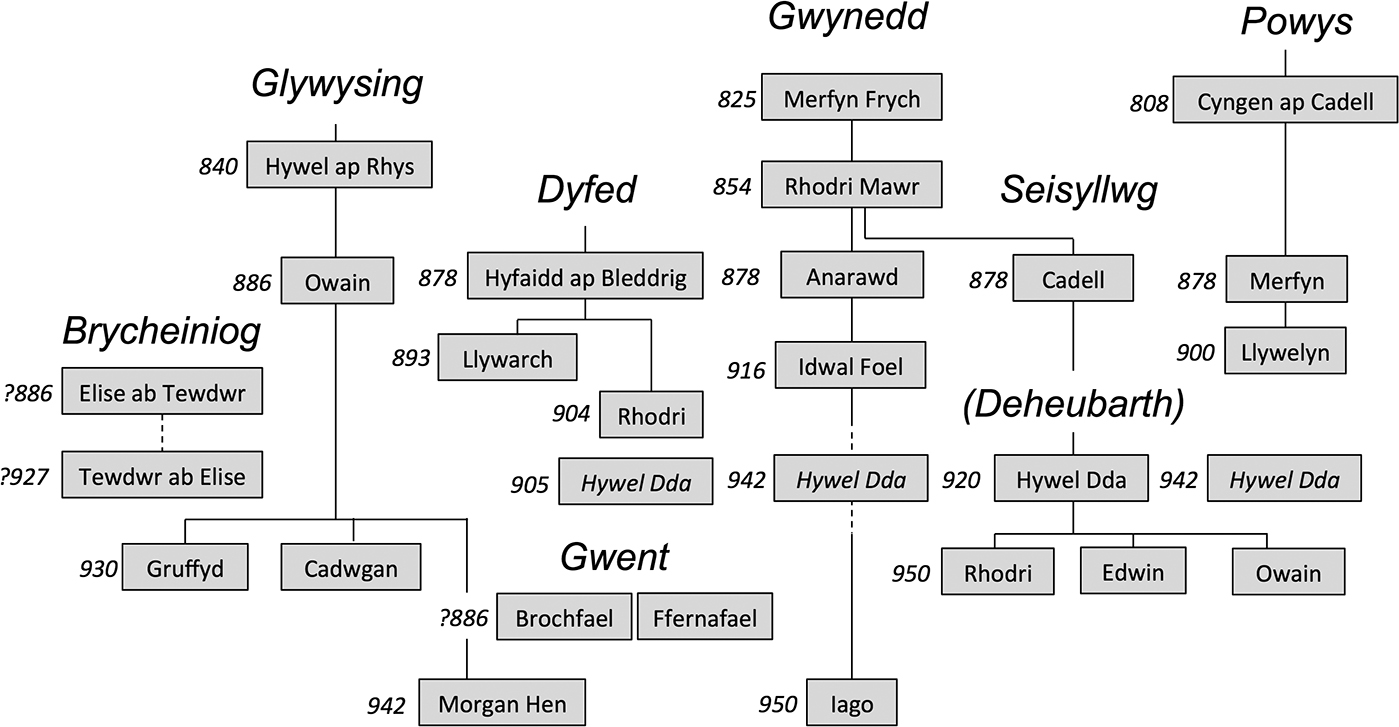

808950

LFREDS BRITAIN IS INTENDED AS A COMPANION volume to my previous Early Medieval histories, The King in the North and In the Land of Giants. Many of the themes, people and places encountered here refer back, one way or another, to those two books. I leave the reader to make the connections.

The word Viking is problematic, and much has been written about its origins, meanings and familiarity to those who found themselves on the wrong end of a Scandinavian raid. Suffice it to say that it is safe to think of viking as an activity: hence, to go a-Viking. It should carry no particular ethnic or national badgealthough, inevitably, it is frequently used as a convenient shorthand for a raider of Scandinavian origin. I have tried to avoid using it as an ethnic label.

A few words are required on spelling and pronunciation. I have tried as far as possible to render spellings in their original language for the sake of authenticity. In Old English, readers will come across letters like the ligature or grapheme , or , which should be pronounced like the a in hat (it comes from the runic letter called sc, or ash, after the tree with which it was associated in the runic alphabet). Less familiar, perhaps, is the thorn, written and pronounced with a soft th, as in think. The eth symbol is a harder th sound, as in that, and appears as when it occurs at the beginning of a word. Anglo-Saxon spelling was itself inconsistent, and it is generally modernized by scholars and translators. Where I have quoted from their work, I have kept their rendering.

Old Norse has its own distinct accents and conventions. Most notably, names like Rgnvaldr have a final r which is silent, and entirely absent in the possessive. So: Rgnvaldr, but Rgnvalds. In Old Irish his name is rendered Ragnall; in the Latin of the Historia de Sancto Cuthberto he is Regenwaldus.

The derivations of place-name forms and meanings are overwhelmingly taken from Victor Watts magnificent Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names. All quotations from translations of the original sources are most gratefully acknowledged. To have almost all of our Early Medieval sources in fine, accessible translations is a monumental scholarly achievement. Two outstanding resources, without which the modern researcher would be stranded, are worth mentioning: the Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE), a searchable database of all the recorded inhabitants of England up until the eleventh century; and the Electronic Sawyer, an online database of surviving charters from the Anglo-Saxon period.

The Viking travel maps started as an aide-memoire to understand how Scandinavians were able to penetrate the remote corners of the island of Britain so effectively, and why it was so hard to stop them. The two versions, early and late, have proved helpful to me; I hope they are equally useful to the reader in making sense of this half-familiar, half-exotic world.

Next page