LFREDS BRITAIN

Max Adams

www.headofzeus.com

From the close of the eighth century, fierce warriors from Scandinavia descended on the undefended coasts of northern Britain. At first they contented themselves with intermittent raids on monasteries with arson, murder and kidnap; but then, in 865, they came to stay. A Great Heathen Host landed in East Anglia, reduced that kingdom to vassalage, established a Norse presence in the southern part of Northumbria, and precipitated a series of wars with the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex that would last until the 950s.

Max Adams traces the heroic efforts of lfred of Wessex, his successors and his fellow kings in Britain to adapt and survive in the face of a new and terrifying threat. He explores the accommodations made between native and incomer, and the forces that led to cultural assimilation and integration among the Scandinavian populations who settled in Britain.

Convention has it that lfred of Wessex, Constantn of Alba and the grandsons of Rhodri the Great are the founding fathers of England, Scotland and Wales, nations forged in the chaos of an age of terror; but lfreds Britain reveals a kaleidoscope of continuing regional diversity, in which the old kingdoms from Kent to Wessex, from Mercia to Lindsey, from Gwynedd to Strathclyde express a patchwork of ineradicable local identities.

Weighing the evidence of chronicle, coinage, excavation, landscape and place name, Max Adams plots a clear path through the shape-shifting complexities of Britains Viking Age.

Contents

For my cousins

A BEAST OF THE IMAGINATION , from a cross shaft at Kirk Braddan old church, Isle of Man

LFRED S BRITAIN IS INTENDED AS A COMPANION volume to my previous Early Medieval histories, The King in the North and In the Land of Giants . Many of the themes, people and places encountered here refer back, one way or another, to those two books. I leave the reader to make the connections.

The word Viking is problematic, and much has been written about its origins, meanings and familiarity to those who found themselves on the wrong end of a Scandinavian raid. Suffice it to say that it is safe to think of viking as an activity: hence, to go a-Viking. It should carry no particular ethnic or national badgealthough, inevitably, it is frequently used as a convenient shorthand for a raider of Scandinavian origin. I have tried to avoid using it as an ethnic label.

A few words are required on spelling and pronunciation. I have tried as far as possible to render spellings in their original language for the sake of authenticity. In Old English, readers will come across letters like the ligature or grapheme , or , which should be pronounced like the a in hat (it comes from the runic letter called sc, or ash, after the tree with which it was associated in the runic alphabet). Less familiar, perhaps, is the thorn, written and pronounced with a soft th, as in think. The eth symbol is a harder th sound, as in that, and appears as when it occurs at the beginning of a word. Anglo-Saxon spelling was itself inconsistent, and it is generally modernized by scholars and translators. Where I have quoted from their work, I have kept their rendering.

Old Norse has its own distinct accents and conventions. Most notably, names like Rgnvaldr have a final r which is silent, and entirely absent in the possessive. So: Rgnvaldr, but Rgnvalds. In Old Irish his name is rendered Ragnall; in the Latin of the Historia de Sancto Cuthberto he is Regenwaldus.

The derivations of place-name forms and meanings are overwhelmingly taken from Victor Watts magnificent Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names . All quotations from translations of the original sources are most gratefully acknowledged. To have almost all of our Early Medieval sources in fine, accessible translations is a monumental scholarly achievement. Two outstanding resources, without which the modern researcher would be stranded, are worth mentioning: the Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE), a searchable database of all the recorded inhabitants of England up until the eleventh century; and the Electronic Sawyer, an online database of surviving charters from the Anglo-Saxon period.

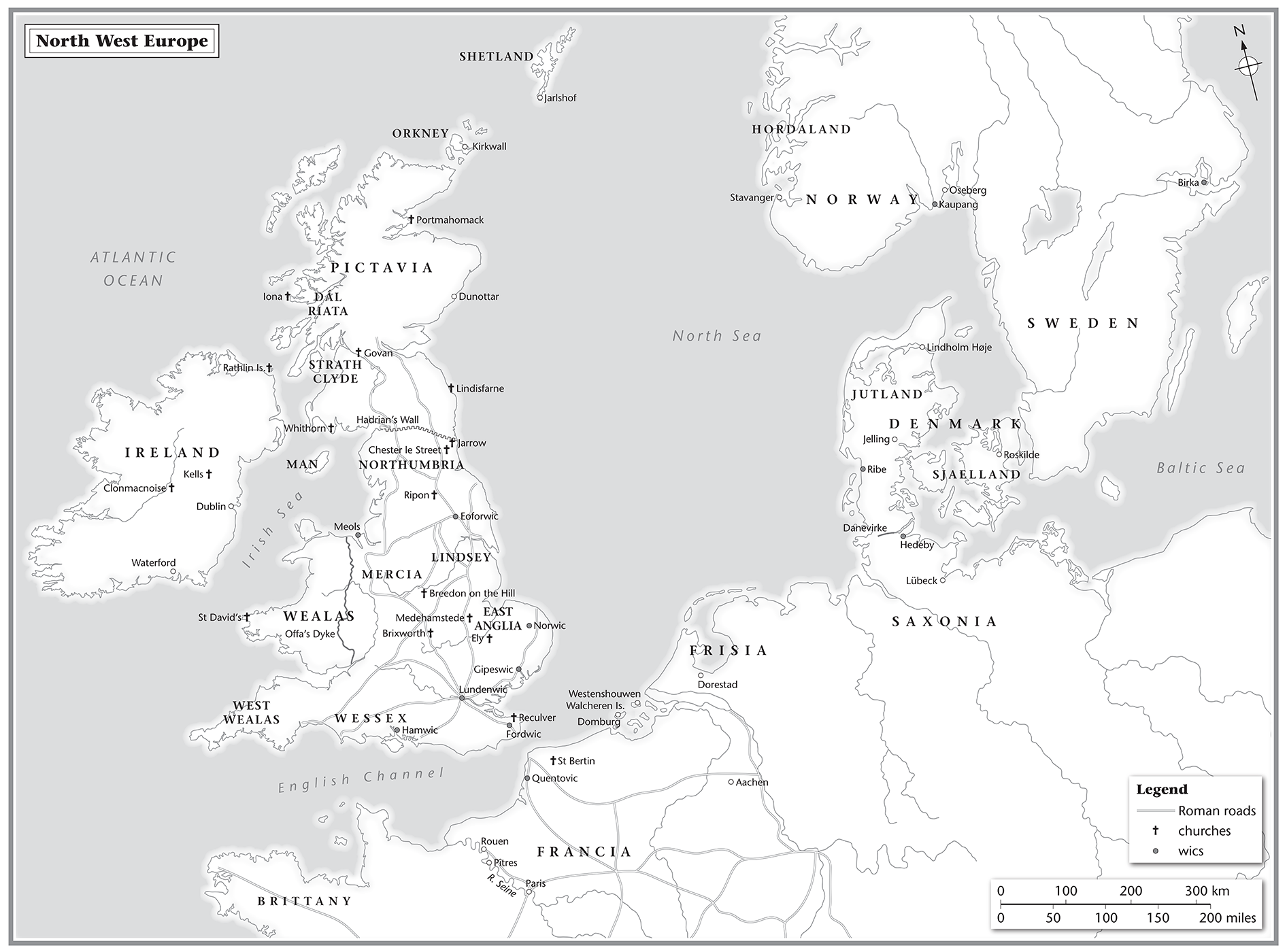

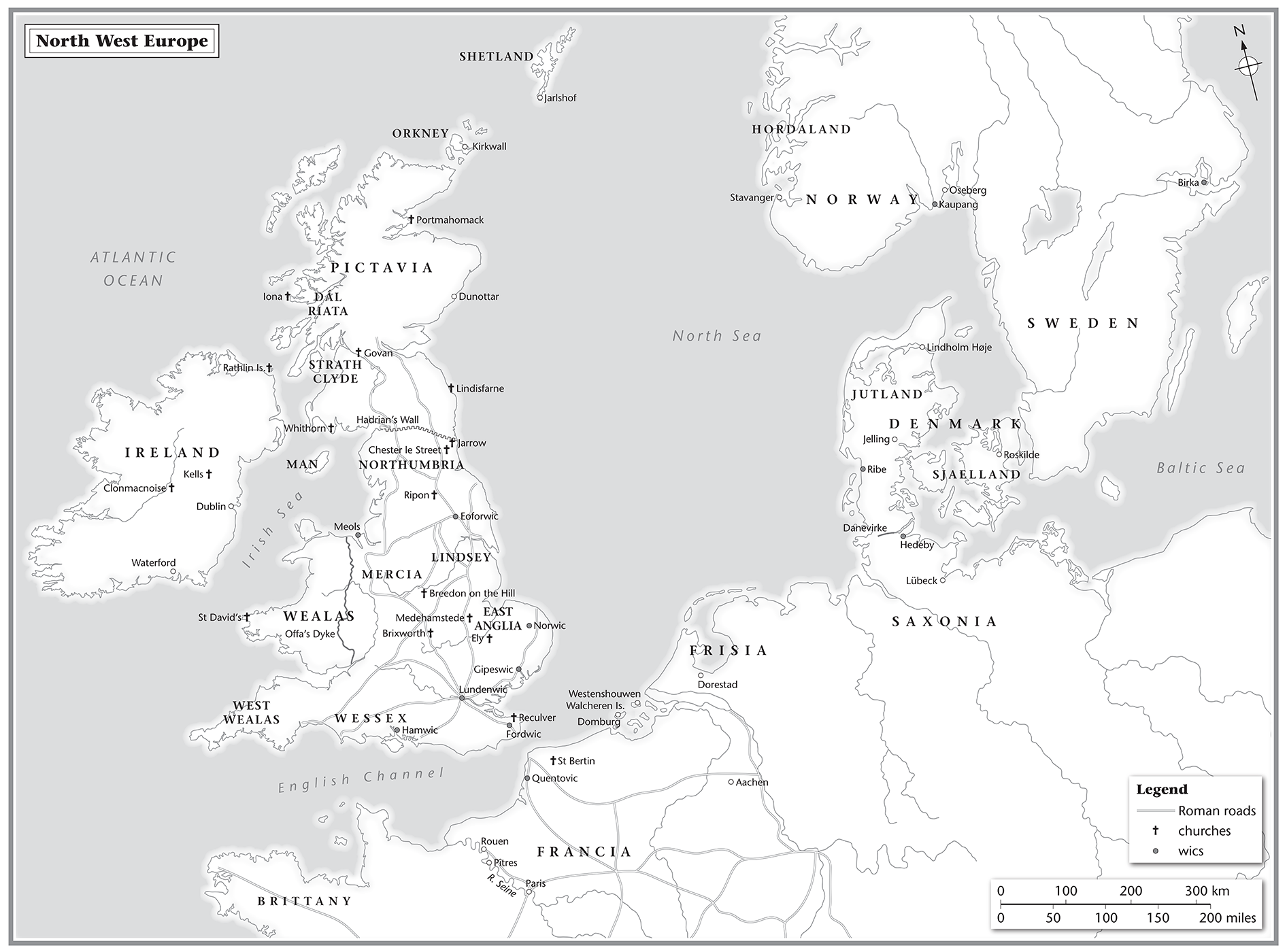

The Viking travel maps started as an aide-memoire to understand how Scandinavians were able to penetrate the remote corners of the island of Britain so effectively, and why it was so hard to stop them. The two versions, early and late, have proved helpful to me; I hope they are equally useful to the reader in making sense of this half-familiar, half-exotic world.

A S THE EIGHTH CENTURY DRAWS TO ITS CLOSE , BANDS of feral men, playing by a new set of rules and bent on theft, kidnap, arson, torture and enslavement, prey on vulnerable communities. Shockwaves are felt in the royal courts of Europe, in the Holy See at Rome. The kings peace is broken. Economies are disrupted; institutions threatened. In time the state itself comes under attack from the new power in the North, a power of devastating military efficiency and suicidally apocalyptic ideology. It seems as if the End of Days is approaching. Out of the chaos come opportunities to shuffle the pack of dynastic fortune, to subjugate neighbouring states, to exploit a new economics and re-invent fossilized institutions.

The economic strengths that made Britain such an attractive target lay in the exploitation, by an organized, self-knowing lite, of abundant resources: its cattle, sheep, grain, timber, minerals and the labour to harvest and process them. The ease with which people and goods were able to move through the landscape, and the institutions which evolved to benefit from that wealth, rendered Britain uniquely wealthy, but also uniquely vulnerable. No king or counsel saw the disaster coming; only, perhaps, the wise and Venerable Bede, wagging a warning finger at the future from his writing desk in 734. After the first shock, a little before the year 800, a centuryfour generationspassed before effective state strategies tamed the wild beast and a new European culture, vibrant, energetic and ambitious, began to take shape. Accommodations were made between native and incomer. In Britain grand projects were conceived: to unify peoples under the banners of kingdoms that came to be known as Scotland, Wales and England. It is not so clear who conceived those projects; even less so that they were successful.

The first notice of a new-dawning reality comes to us from an entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle under the year 789. In this year, it was remembered, three ships came out of the North. Presuming them to be traders, the West Saxon kings man of businesshis portgerefa , or port-reeverode to meet them somewhere on the south coast, perhaps Portland in Dorset. They slew him. Within a decade, a rash of notices recorded the sacking of monasteries along the North Sea coasts of Britain, among the Hebridean islands and as far west as Ireland. The famous attack on Lindisfarne, Holy Island, in 793 was and is seen as a marker for the start of a new European age of warfare, uncertainty and migration.

![Haywood - Viking: The Norse Warrior’s [Unofficial] Manual](/uploads/posts/book/98981/thumbs/haywood-viking-the-norse-warrior-s.jpg)