STRATHCLYDE

and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

ISBN: 978 1 906566 78 4

eISBN: 978 1 907909 25 2

Copyright Tim Clarkson 2014

The right of Tim Clarkson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Britain by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow

CONTENTS

LIST OF PLATES

LIST OF MAPS

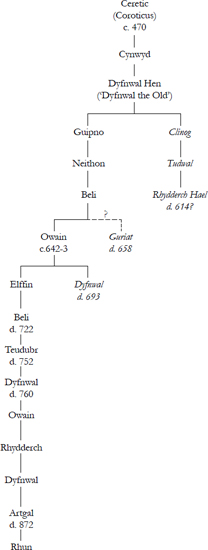

GENEALOGICAL TABLES

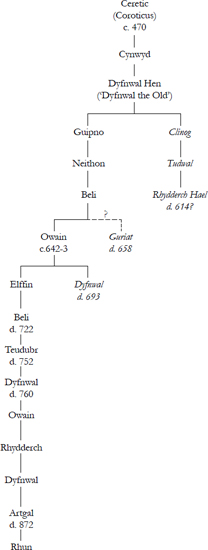

Kings of Alt Clut, fifth to ninth centuries, based on the Harleian pedigree of Rhun, son of Artgal. Names in italics are from sources outside the pedigree.

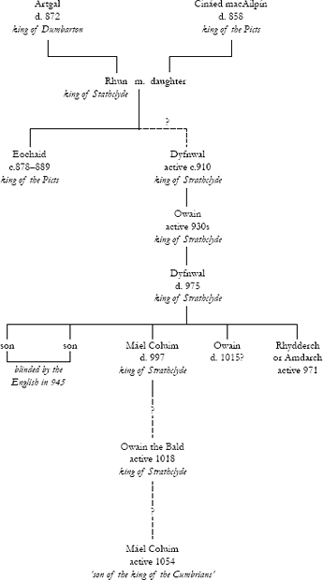

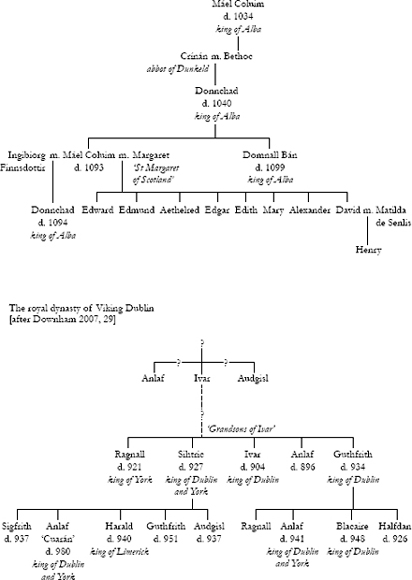

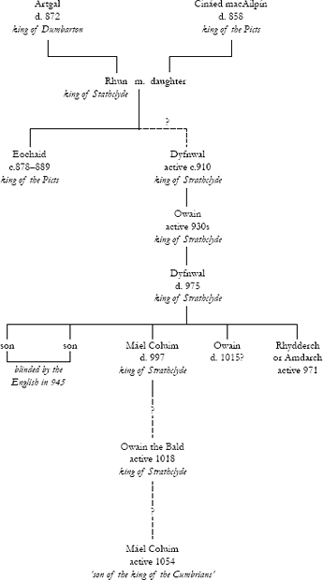

The royal dynasty of Strathclyde

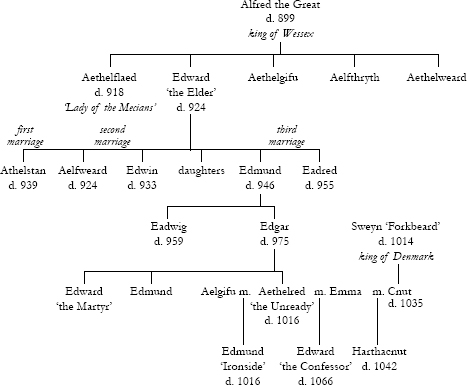

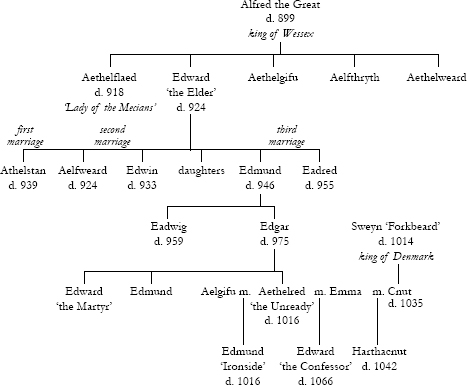

The royal dynasty of Wessex

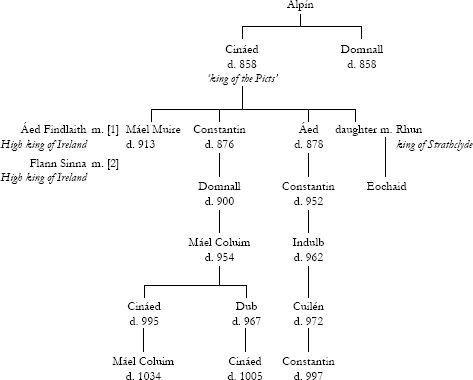

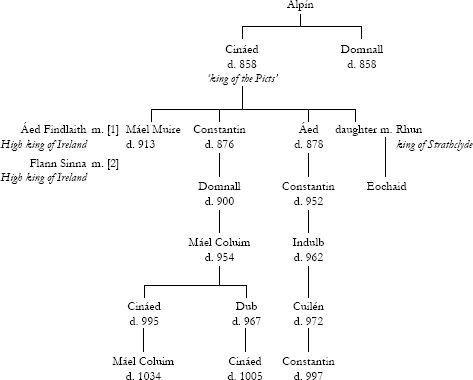

The royal dynasty of Alba to 1034

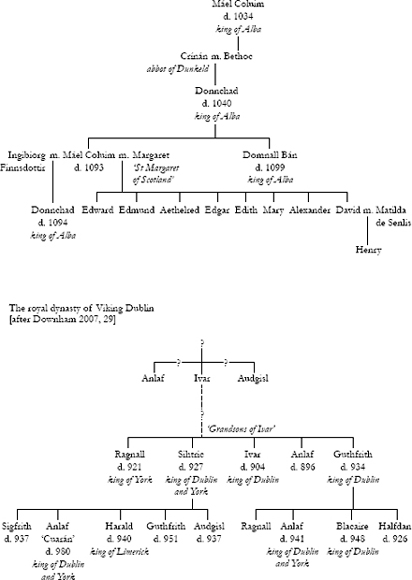

The royal dynasty of Alba, 11th to early 12th centuries

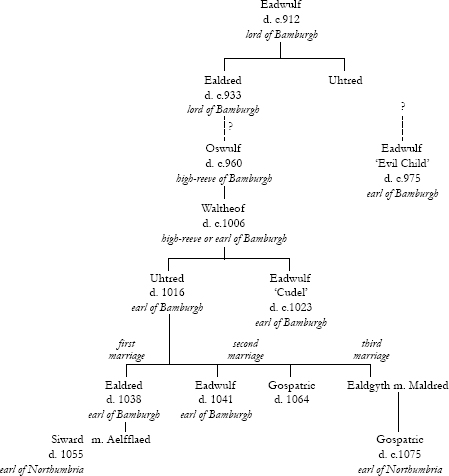

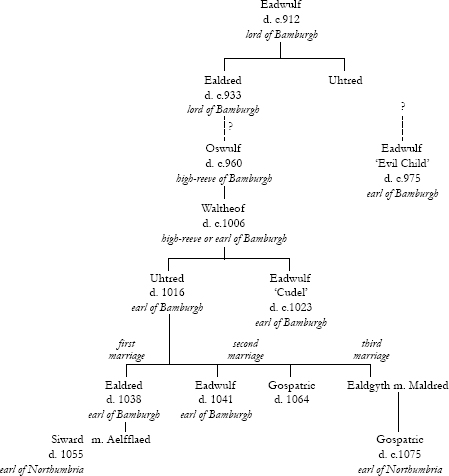

The dynasty of Bamburgh

CUMBRIANS AND ANGLO-SAXONS

Introduction

One thousand years ago, at the beginning of the eleventh century, the valley of the River Clyde was the heartland of a powerful kingdom. In those days, the river flowed through a rural landscape devoid of towns and cities. From its sources in the hills, it meandered north-westward for many miles before widening to form the estuary we know today as the Firth of Clyde. Eleven miles upstream from the head of the firth, and two miles downstream from the site of modern Glasgow, an important ford provided a crossing-point. Here, at Govan, travellers on foot could traverse the river at low tide. It was here, too, that the Clyde was joined by the River Kelvin coming down from the north. Directly opposite the confluence, on the southern bank of the Clyde, the ford was overlooked by a huge mound with two levels and a flattened summit. Further along the southern bank, no more than a stones throw from the mound, stood a small wooden church in a heart-shaped enclosure. The mound has long since disappeared, a casualty of nineteenth-century industrialisation, and no trace of it remains today. But a church still stands nearby, the most recent successor of the wooden church of a thousand years ago. This impressive Victorian building, known today as Govan Old, is home to a remarkable treasure: an internationally renowned collection of early medieval sculpture. Visitors come from far and wide to admire the finely carved monuments, all of which formerly stood in the churchyard amidst the gravestones of later times. Among the collection are an ornate sarcophagus, three broken cross-shafts, five hogback gravestones and more than twenty recumbent slabs. Each of the thirty-one stones at Govan Old is a reminder of the skill and artistry of local craftsmen who developed their own distinctive style of carving. The patterns and motifs on these stones are similar to those on contemporary sculpture in other parts of the Celtic world panels of interlace, figures of humans and animals, religious symbols but the art of the Govan monuments is otherwise unique. This remarkable collection bears witness to the wealth and power of the long-vanished kingdom of Strathclyde.

Strathclyde is the modern, Anglicised form of a name recorded in ancient sources as Strat Clut or Strad Clud. Both names share the same meaning and a similar pronunciation, having been formed in what was essentially the same ancestral language. This book is chiefly concerned with one aspect of the story of the Cumbri or Cumbrians, namely their relations with the Anglo-Saxons or English who dwelt beyond their southern and eastern borders.

Chronological scope

The following chapters are chiefly concerned with a 350-year period running from the middle of the eighth century to the beginning of the twelfth. This corresponds roughly to the second half of the early medieval period or Dark Ages. It contains the main era of Viking raiding and colonisation (ninth to eleventh centuries), the emergence of the kingdom of Alba (late ninth to early tenth) and the Norman conquest of England (late eleventh). Earlier centuries are covered more briefly, to provide a necessary historical background for the main narrative. In of the Anglo-Scottish border. For the entire period spanned by the book, the term early medieval is generally preferred to Dark Age, chiefly because the latter can all too easily conjure negative images of barbarism. Both terms refer to a period of roughly six or seven hundred years following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century AD.

Terminology

Throughout this book, the people of Viking-Age Strathclyde are frequently referred to as Cumbrians. In modern usage this is, of course, a term more commonly applied to the inhabitants of the English county of Cumbria. Applying the same term to a people whose kings dwelt a few miles west of Glasgow might seem puzzling, but no confusion or anachronism is intended. In this book, Cumbrians is used in its early medieval sense, as a synonym for North Britons, rather than in relation to any modern administrative entity. In medieval chronicles in which the history of the ninth to eleventh centuries is preserved, Cumbria was a Latin term denoting an extensive territory ruled by the kings of Strathclyde. It was used as a collective name for all lands inhabited by the Cumbrians or North Britons and was not restricted, as it is today, to a region south of the Solway Firth. The language spoken by the Cumbrians was a Celtic language similar to Old Welsh. Specialist scholars now refer to it as Cumbric, to distinguish it from related languages such as Cornish, Breton and Welsh. These four languages, together with Pictish, belong to a group known as Brittonic or Brythonic because they evolved from the common speech of the Britons, the ancient inhabitants of the whole island of Britain. A second group of Celtic languages includes the Gaelic speech of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In this book, the main language of the kingdom of Strathclyde is usually referred to as Cumbric, occasionally as British, but never as Welsh. Although their English neighbours regarded the Cumbrians as