The Picts

This eBook edition published in 2012 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Tim Clarkson 2010

First published 2008 by Tempus Publishing

This revised edition first published in Great Britain in 2010 by John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

The moral right of Tim Clarkson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-906566-25-8

eBook ISBN: 978-1-907909-03-0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Contents

Preface

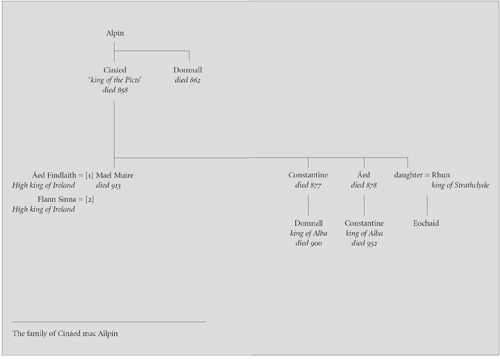

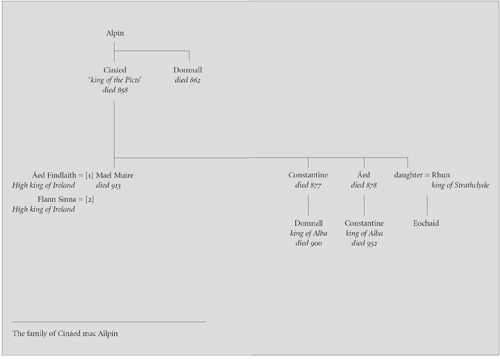

The first edition of this book appeared in early 2008. Since its publication my views on several aspects of Pictish history have changed, particularly with regard to relations between Picts and Scots during the ninth century. By the end of 2008, the final chapters were already at odds with my altered perception of Cined mac Ailpn and his conquest of the Picts. It was with this new perception in mind that I made reference to Cined in my recently-published book The Men of the North: the Britons of Southern Scotland. At the same time an opportunity arose to produce a new edition of The Picts: a History. It seemed an appropriate moment to bring the two books in line with one another.

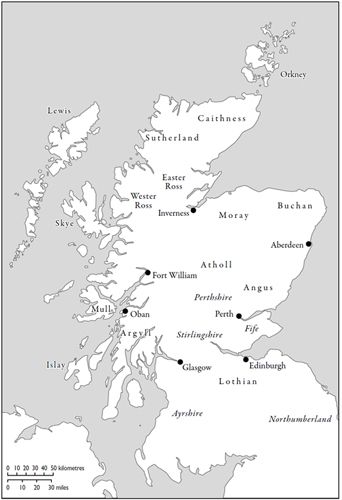

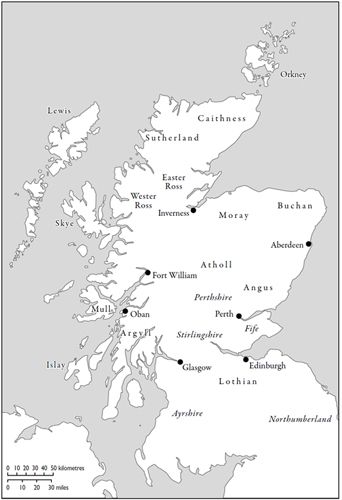

In the case of The Picts, the changes relating to the end of the Pictish period have been accompanied by a geographical shift regarding the location of Fortriu. The 2008 edition adopted an older belief, now generally regarded as mistaken, that this region lay in Perthshire. Historians now prefer to locate it further north, in Moray, and the growing consensus is duly reflected here. In revising and updating The Picts I have retained the character of the 2008 edition which was, after all, intended to be a non-academic work. The various changes have not caused a major disruption to the style of the original narrative.

The bibliography has been expanded in this new edition to include a wider range of literature grouped by subject. It now lists a larger selection of books and journal articles but remains a fairly informal guide to further reading. The equally informal appendix of Pictish puzzles is little changed, except in the sections relating to Cined mac Ailpn, Fortriu and the Gaelicisation of the Picts. One visual difference between the two editions is the presentation of illustrations, the photographs having been reduced in number to make way for maps, drawings and genealogical tables. This reorganisation has, I believe, enhanced the aesthetic appeal and overall usefulness of the book.

Tim Clarkson

June 2010

The Scottish Highlands: a selection of modern territorial divisions.

CHAPTER 1

A People Apart

Picts was the name given to a people who inhabited a large part of what is now Scotland during the first millennium AD . Together with their neighbours Scots, Britons and English they played an important role in the early history of the British Isles. They make their first appearance in the historical record at the end of the third century when their raiding activities troubled the authorities of Roman Britain. After less than 600 years, they seem to vanish from the pages of history, leaving behind no written records of their own nor any significant trace of their language. In the wake of their apparent disappearance a fictional tale was created to explain it, and a shroud of myth enveloped the true story of their fall from power. From these legends there emerged a belief that the Picts were a mysterious race whose history was unknown: a strange, almost alien nation who were very different from their neighbours. They became, in other words, a people apart.

The modern visitor to the Highland areas of Scotland usually encounters the Picts through their spectacular artistic legacy. This is most vividly represented by several hundred finely carved stones, many of which are still visible in the landscape. A large number of these stones bear esoteric designs which are repeated and replicated with remarkable consistency across a wide geographical area, from Skye to Aberdeen and from Shetland to Fife. The meaning of these symbols defies interpretation and, despite numerous attempts to decipher them, their original purpose remains an enduring puzzle. It is perhaps ironic that the symbol stones the most impressive legacy of the Picts make this ancient people seem even more mysterious.

This book seeks to venture behind the myths and legends to find the real history of the Picts, to de-mystify them in so far as it is possible to do so. It does not take a themed approach, in which aspects of society and culture are discussed as separate topics, but adopts instead a linear structure guided by a simple chronological framework. The span of this chronology is the era of the historical Picts, covering the years 300850, with some leeway at the beginning and end. This span includes much of the so-called Dark Ages, a term applied rather loosely to the centuries of transition between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the end of the eleventh century. The phrase Dark Age Scotland certainly has a dramatic impact and conjures an image of mist-shrouded hills brooding in a Celtic twilight, but it also carries negative overtones of ignorance and gloom. As an alternative to Dark Age, the more neutral term Early Historic is therefore used throughout this book.

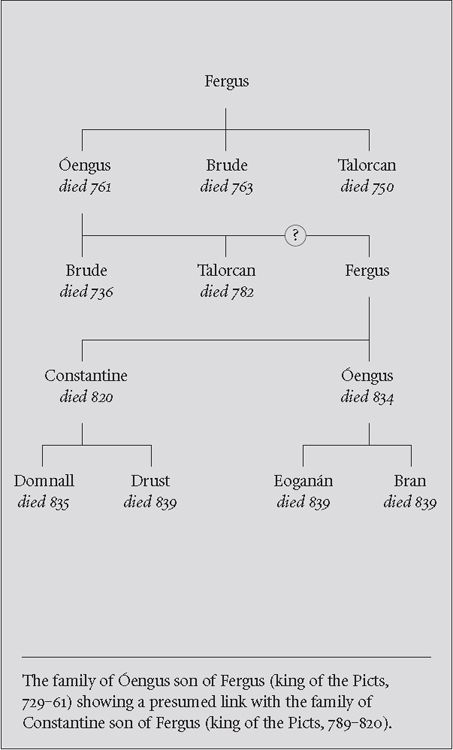

Documentary Sources

This is not meant to be an academic textbook, nor a scholarly investigation, but a narrative history presented as an unfolding sequence of events. The chronological framework guiding the narrative is a list of Pictish kings. This king-list survives in a number of medieval manuscripts which differ slightly from each other in the information they provide. They ultimately derive from an original text that is now lost. This was written at an unknown Pictish monastery and later came into the hands of medieval Scottish monks, whose own versions of it are seen in the surviving manuscripts. In the interests of simplicity the various versions are treated throughout this book as a single source referred to here as the king-list. In reality, the manuscripts fall into two groups, each of which incorporates variant versions of the list together with additional notes relating to the Picts. The basic format of each version is a sequence of some sixty kings giving their reign-lengths and their fathers names. Based on the chronology of the reigns it becomes apparent that the line of kings begins in the fourth century and ends in the ninth. Recent analysis of the manuscripts has shown the value of the list as a source of data for Scotlands early history, but it has also revealed its shortcomings. Thus, although early versions existed in written form as early as the eighth century, the oldest surviving manuscript is a product of some six centuries later. This means that the text needs to be treated with caution if it is to be employed as a signpost to the Early Historic period. Fortunately, the information it provides for people and events from AD 550 to 850 is frequently corroborated by other sources. This kind of cross-referencing makes the king-list a fairly trustworthy source for the main era of Pictish history between the sixth and ninth centuries.