Robert Colquhoun, Figures in a Farmyard, 1953. Along with Robert MacBryde, Colquhoun created a style that draws both on the work of the Polish exile Jankel Adler and on links with the English neo-Romantic artist John Minton.

About the Author

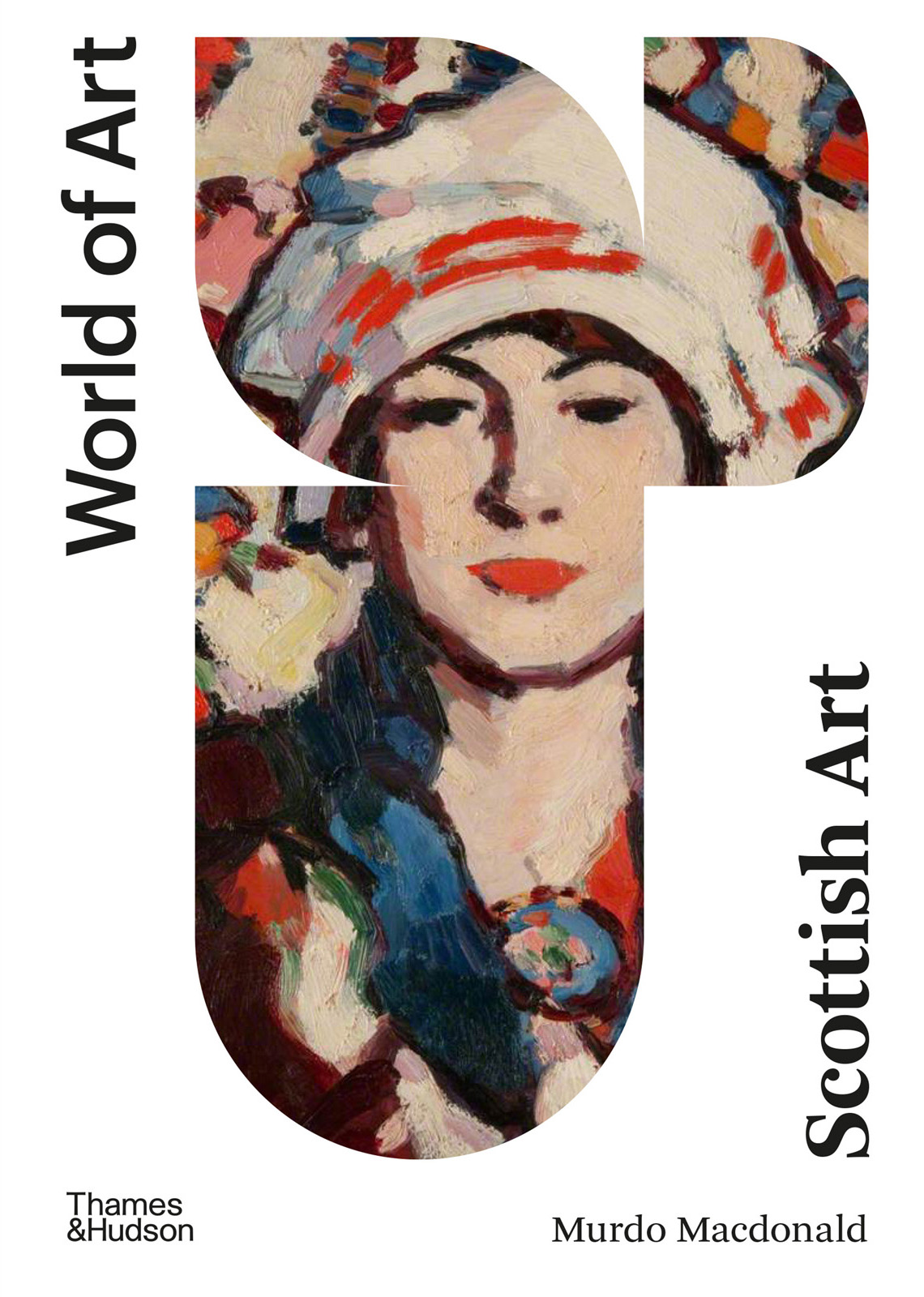

Murdo Macdonald is emeritus professor of the history of Scottish art at the University of Dundee. In his doctoral research at the University of Edinburgh he studied the relationships between art and science. He is a former editor of Edinburgh Review. His research has explored, among other things, the cultural revival milieu of Patrick Geddes, the art of the Scottish Gidhealtachd, visual interpretations of the life and work of Robert Burns and the aesthetics of the cloud chamber photography of the Scottish physicist and Nobel laureate C. T. R. Wilson. He has a long-standing interest in Ossian and art in an international context. He was appointed an honorary member of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture in 2009, and an honorary fellow of the Association for Scottish Literary Studies in 2016.

Contents

James Guthrie, A Hinds Daughter, 1883. Direct in composition, in subject and in technique, Guthrie creates an image of rural life that, despite shared influences, contrasts markedly with the paintings of gentler pastimes so favoured by Lavery.

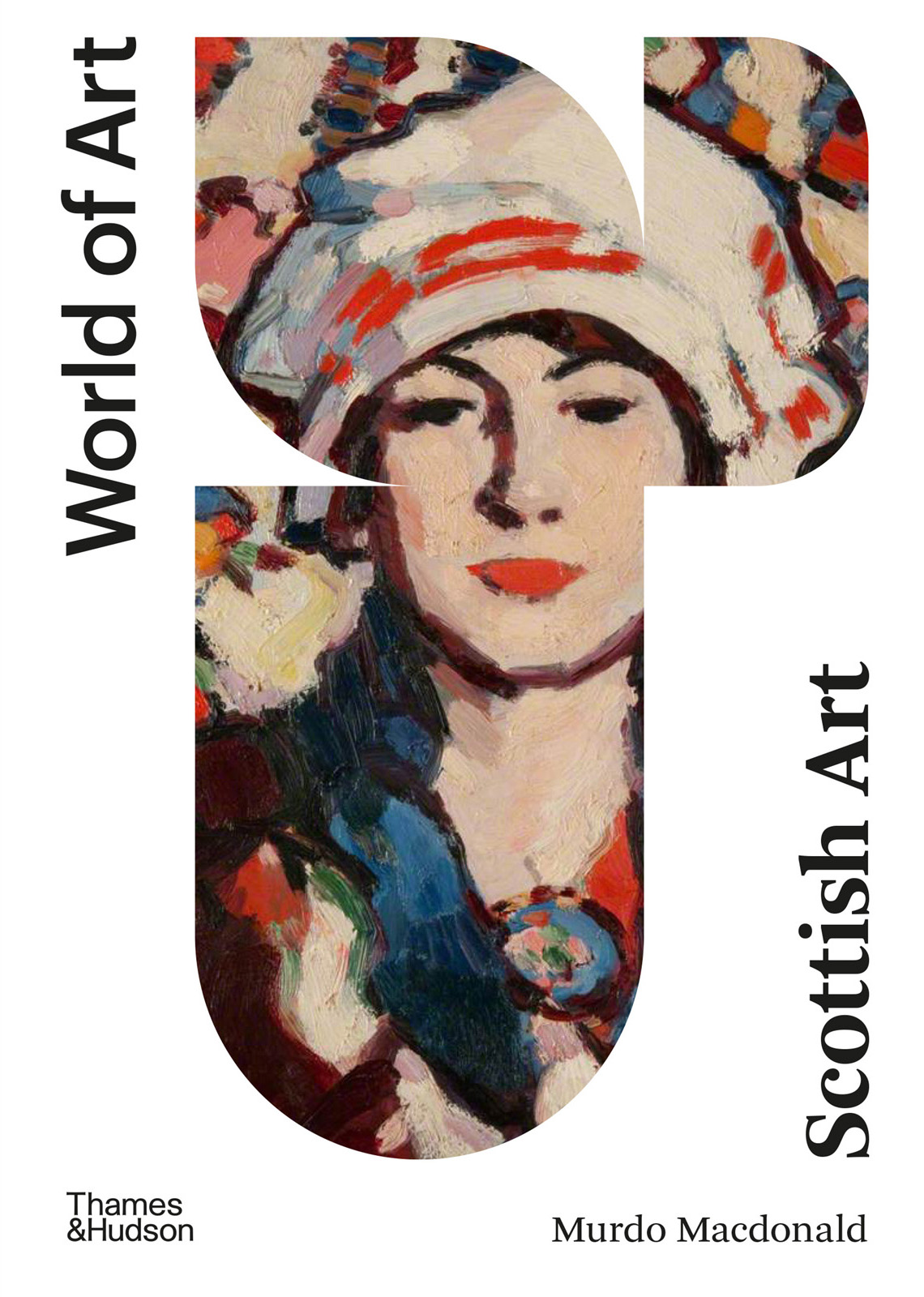

Since this book was first published twenty years ago there has been a widening appreciation of the significance of Scottish art. The redevelopment of the National Gallery of Scotland to enable its historical collection to be exhibited more effectively is but one indicator of that. Another is the success of the Royal Scottish Academy not only as a professional body but also as a powerful advocate for artists just out of art school. That strength was reflected in the remarkable exhibition Ages of Wonder: Scotlands Art 1540 to Now held at the Academy in 2017. It gave rise to a book of the same title and I take the two together as representative of the growing vitality of research into, and exhibition of, Scottish art.

In this new edition I have focused on making some small corrections and bringing the book up to date. The main body of the text remains as it was and my hope is that it will again stand the test of time as an introductory text. The key difference in this new edition is that developments over the last twenty years have been included by adding to the body of chapter 8 and making the epilogue into a new chapter 9. The other difference is that this new edition has been fully redesigned and has more images, almost all now in colour.

Most Scottish art in existence today was made after the Reformation. The period from Neolithic times to the Reformation is therefore presented in this chapter and the one that follows as a preamble. Works from the early period, for example the standing stones of Calanais, the Book of Kells and the stone carvings of the Picts, have nevertheless a high degree of interest both historical and aesthetic and their direct influence is felt in much later work up to the present day.

The First Art

There were people living in Scotland at least nine thousand years ago, establishing communities as the country became habitable in the wake of the last Ice Age, but they left little trace until farming became established over six thousand years ago. With agriculture came a more settled lifestyle enabling the establishment of fixed living sites and buildings of wood or stone. Traces of early settlements still survive, for example the interlinked houses at Skara Brae in Orkney which date from between about 3500 BC and 2500 BC. Among the finds at Skara Brae were small objects of carved stone which make an immediate aesthetic impact. They are part of a wider culture of visual and tactile expression throughout Scotland, which includes standing stones, cup and ring marks, maceheads and carved stone balls. These objects all have a quality that brings them into the category of art: they have an unambiguous beauty and their function is psychological, not practical. This is true even in the case of maceheads, which, while they derive ultimately from designs for utilitarian objects or weapons, have few traces of wear and it is clear that they were made for symbolic rather than physical use.

Standing stones, Calanais, Isle of Lewis, c. 3000 BC. The visual thinking of the early inhabitants of Scotland as expressed by stone circles is of enduring fascination. They relate equally to the landscape and to the skies; aesthetic presence is united with astronomical relevance.

Because of the Ice Age, the art of Scotland has no Palaeolithic period, but the Neolithic art such as the standing stones throughout Scotland, in particular the groups sited in and around Calanais in Lewis (c. 3000 BC), and the Stenness/Brodgar complex in Orkney, makes a remarkable impact.[] Martin Martin in 1695 described the Calanais stones as a heathen temple. Over a century later Sir Walter Scott referred to the stones of Stenness as a stupendous monument of antiquitycalculated to impress on the feelings of those who behold it. In 1995 the art historian Duncan Macmillan wrote of Calanais that these stones were surely the object of pilgrimage. But getting further than this obvious spiritual and ceremonial function of standing stones is difficult. The fact that they relate with a precise geometry to the features of the land on the one hand and to sun, moon and stars on the other is not in doubt. Whatever their function, these stones leave us in awe of but also in touch with the imagination of the people who created them in the third millennium BC.

On a smaller scale maceheads and carved stone balls are also works of sculptural presence. Maceheads have been discovered at burial sites and this suggests that they have a personal significance. Carved stone balls, however, are not found typically at burial sites and this strengthens the frequently made suggestion that they were symbols of power with a social-ceremonial use, passed from one holder to another, rather than buried along with one person. Perhaps, in the language of these people, the phrase holding power meant literally that. Furthermore, each carved stone ball is markedly different from every other and this distinctiveness again suggests the holding of symbolic power within different groups. About four hundred examples have been found, for the most part between the River Tay and the Moray Firth in the fertile area bounding the southern and eastern edges of the Grampian Mountains. Only four examples of this type of work have been found outside Scotland: two in England, one in Norway, one in Ireland. This uniqueness does not, however, extend to the decorative elements; for example, the Towie Ball (c. 3000 BC) in its complex spiral design brings to mind the great Neolithic carvings of Newgrange in Ireland and Pierowall in Orkney, despite the difference in scale.[] Three millennia later this same eastern area of Scotland became the heartland for the making of Pictish symbol stones and understandably enough some archaeologists at first supposed the carved stone balls to be Pictish work.

Next page