Page List

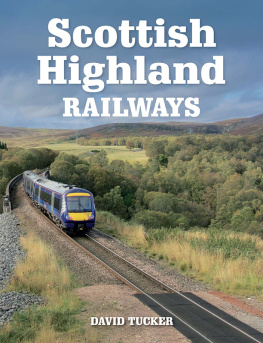

Scottish

Highland

RAILWAYS

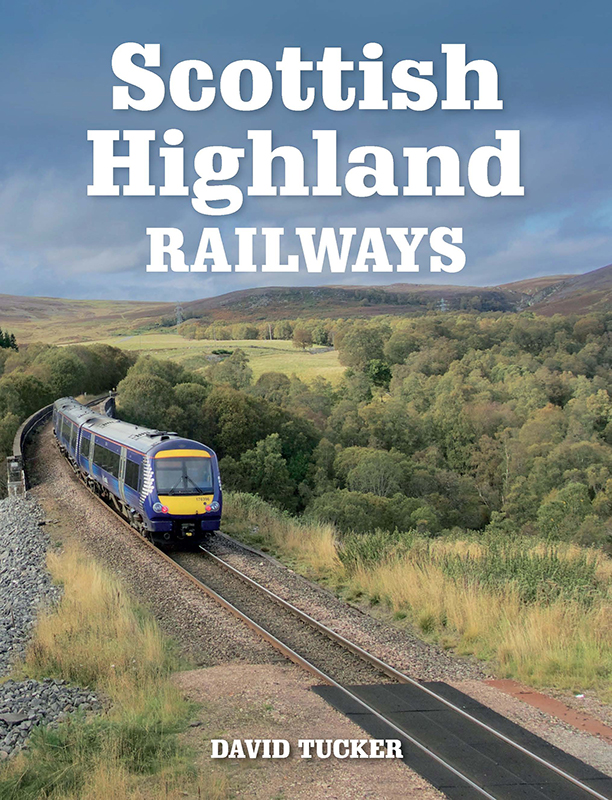

West Highland Line between Tyndrum and Bridge of Orchy, looking to Beinn Odhar.

Scottish

Highland

RAILWAYS

DAVID TUCKER

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

David Tucker 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 793 4

Illustrations

The majority of the photographs are the authors originals; others are credited individually. With special acknowledgment to the following: the Museum of Scottish Railways (The Scottish Railway Preservation Society), John Robin, Norman McNab, Sarah Bromage, iStock.com by Getty Images (various individuals), Picfair (various individuals), Wikimedia Commons and Open Street Map.

Preface, Definitions and Terminology

Scottish Highland Railways is one of a series of railway books from Crowood that cover both the hobby of modelling (more than fifty titles published) and the history of the railways themselves. Since 2014 the latter titles have covered, on a regional basis, the railways of Lincolnshire, Shropshire, Ayrshire, Telford and other UK regions.

The present book differs from these published titles in a crucial way, due to the vast geographical scale of railways serving the Highlands of Scotland. There are eight long lines running into and through the Highlands, plus, of course, the lost lines that any regional history must cover. This scale reduces the opportunity for providing too much local detail, although the book does include extensive sourcing and referencing for those wishing to delve into local, historical railway detail (for example, books focusing on the West Highland Line or the Great North of Scotland company, and also online resources). There is no shortage of publications and online sources covering the history of the railways in Scotland, among them P.J.G. Ransoms comprehensive Iron Road The Railway in Scotland (Berlinn, 2007), David Spavens The Railway Atlas of Scotland (also from Berlinn, 2015) and Getting the Train: The History of Scotlands Railways, by David Ross (Stenlake, 2018).

The geographical extent and the nature of the network in the Highlands means that history is best dealt with line by line, rather than in a strict chronology of railway companies. There was originally little in common between, for example, the Dukes railway in distant Sutherland and the West Highland connecting Helensburgh to Glasgow, or the Royal Deeside line taking Queen Victoria and her guests to Balmoral Castle. A strict chronological approach would drag the reader from one side of Scotland to the other within each of the formative decades (for example, the 1890s) so chronology is presented within the chapters dedicated to each of the distinct railway lines (for example West Highland, East Coast, Far North).

An exception can be made, however, for the single chapter covering the twentieth century. It may seem odd to offer several chapters covering line development between 1840 and 1900 and only one for the twentieth century, but as the introduction to that chapter will explain, the Highland railway network was more or less complete by the early 1890s, and the main changes affecting it in the twentieth century would be national or even international rather than localized. These included the impact of two World Wars, the Grouping into larger rail companies, nationalization (into British Railways) and then privatization, these events accompanied by broad social and technological changes: the rise of car ownership, the demise of steam, and the impact of Beeching (explained below under Terminology).

Although historical by nature, the book also examines trends and events in the early twenty-first century that are underpinned not only by changes in railway management (the franchise system), but also by technology and political changes, such as devolved powers for the Scottish government regarding public transport. This century has also brought a refreshing revival of interest in both modern rail and heritage lines, not least among tourists to Scotland interested in riding The Jacobite steam-hauled trains over the Glenfinnan viaduct, made world famous in the Harry Potter movies.

Note on publication date: This book was written mainly during 2019 for publication in early 2020 but the global pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus delayed publication into 2021. The pandemic and its lockdown also delayed impending government decisions on the future of UK railways (the postponed Williams Review) and, in Scotland, on the ScotRail franchise. Furthermore, the pandemic introduced uncertainty over the UKs planned exit from the European Union (Brexit) that would ultimately influence railways in the Scottish Highlands.

Given its historical emphasis, the book was not greatly affected by the events of 2020, but the perspective of , Scottish Highland Railways in the Twenty-First Century, should be read in this context.

Defining the Highlands

There is a geological definition enshrined in the Highland Boundary Fault, but this has little relevance in terms of human settlement and therefore of the transport network. Instead, coverage starts at the northern extremity of the Central Belt the low-lying area stretching from Glasgow to Edinburgh and extends all the way northwards to the coast at the UKs most northerly railway station, Thurso, by way of Fort William in the west, Inverness in the centre and Aberdeen in the east.

Politically, Highland Council is the largest of the local government areas in Britain, with an area of nearly 10,000 square miles (including the former counties or shires of Inverness, Ross, Cromarty, Caithness and Sutherland). The term Highlands and Islands is still used by some organizations (for example by HITRANS Highlands and Islands Transport Partnership), but it now has no political relevance. The islands the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland have no railways, but there are important links from ports with railway stations for transferring to ferries (Aberdeen, Oban, Mallaig, Kyle of Lochalsh, Thurso and Wick).

Like Highlands and Islands, Grampian has disappeared from the political lexicon but remains useful for defining a large north-eastern corner of Scotland, nowadays containing the council areas of Aberdeen City, Aberdeenshire and Moray. An understanding of railway development in this region is crucial to understanding the evolution of northern Scottish railways.

Finally, there are Highland lines that start (or end) in the northern reaches of the counties of Perth and Kinross, Argyll and Bute, Stirling and Angus, and all these therefore straddle highland and lowland and need to be considered.