The History Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the Marc Fitch Fund

CONTENTS

by Andrew Scott CBE, Former Director of NRM

Relationship of Metric to Imperial Units

Railway Companies

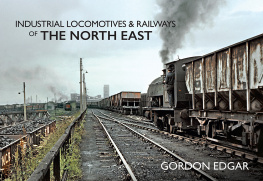

The North Pennine dales are a very special place one the emptiest places in England, apparently on the road to nowhere, a land of high fells, wide and wild valleys where farming is utterly at the margin.

It is a land where population would have been negligible had it not been for the rocks and minerals for which the area has become well known. Quarries yielded stone limestone, sandstone and hard whimstone for road works. But igneous activity had also introduced mineral-rich magma, cooling in cracks forced through the rocks and a rich source of important metals and other chemicals. Mining and quarrying became important industries.

As a teenager from the English midlands, I made a pilgrimage with my family to discover where my grandfather had been born, somewhere so different from the modern city where I had been brought up that I have never forgotten that first visit. The place was Harwood in Upper Teesdale, about as wild and remote as one can get in England. My grandparents family had been farmers and lead miners nearly 2,000ft up in some of the most inhospitable conditions that England has to offer. Life was hard and, by the early twentieth century, it was obvious that the future held little hope, so they emigrated to Frinton on Sea but that, as they say, is another story. Tom Bells fastidious research, published here for the first time, opens the door for me to new facets of my familys history.

For some of the area, the coming of the railway added impetus to quarrying and mining and led to a hundred years of intense economic activity. In the more remote parts, the twin challenges of landscape and economics meant that the railway did not materialise. Transport costs remained high and mining remained a marginal industry. Dr Bell has uncovered the story of the railways that were prepared to confront challenges of the 2,000ft high passes and deep valleys. He paints a picture of what might have been and, in so doing, helps our understanding of the achievements of the miners of the north Pennines and of the limitations that have left this country so lonely today. For those who love this part of the world and the faint traces of its fascinating industria history that remain, he has added a new dimension to the story.

Andrew Scott CBE,

Former Director, National Raillway Museum

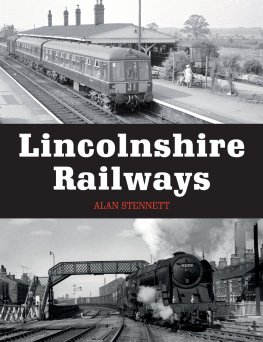

The idea for a book outlining the history of the various railway proposals in the North Pennines arose during a study of the nineteenth-century documents relating to the planning, building and later proposals to extend the Alston branch of the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway (N&CR). The majority of people with an interest in railways will have heard of the Alston branch and most of these, as well as many others, will be familiar with its current reincarnation as the narrow-gauge South Tynedale Railway. Similarly, the Wearhead branch is also well known at the time of writing, especially in preservation circles, in its various recent reincarnations as the Weardale Railway. The Middleton-in-Teesdale and Allendale branches, both of which started life as totally independent concerns, are rather less well known, while knowledge of the Stanhope and Tyne, the Wear and Derwent Junction, and Weardale Iron and Coal Company Railways is even more restricted, especially in the case of the latter which was never a public railway and which therefore rarely appears on the various railway maps depicting the pre-grouping era. Those interested in the development of the British railway network will probably have heard of proposals to connect the valleys of the South Tyne and Wear and possibly also the South Tyne and Tees, while the more serious student will be able to name these schemes as the Wear Valley Extension Railway (of 1845) and the Cumberland and Cleveland Junction Railway. What is perhaps less well understood is that these lines were not simply speculative proposals of the Railway Mania, or later, but were genuine proposals, whose supporters were active for over half a century, with the second line coming very close to actually being built.

My interest in railways, and my connection with the North Pennines, extends over all of my almost eighty years. Until I was seven, we lived in the East Allen Valley, a mile north of Allenheads, where I was fortunate to see the last, decaying years of the local lead industry. During that period I was taken, by my father, to Allendale station to collect parcels, although I do not remember ever seeing a train at that rather inconvenient station. In my teens, I cycled over most of the North Pennines, seeing the inclines at Hallbankgate and Stanhope in action, while passenger trains at the railheads of Alston, Middleton-in-Teesdale, Tow Law and Wearhead were all familiar. I especially remember the station at Alston, with its overall roof, which made it an ideal place to eat ones sandwiches in inclement weather. After twenty years away from the North Pennines, I returned with my family, moving into Alston the weekend the branch closed. This research started three years later, when I produced a small display for the developing South Tynedale Railway Preservation Society. Since that time I have discovered the true extent of the vast efforts made to provide rail connections over the roof of England. I would not claim to have unearthed every piece of relevant information, but certainly there is a much greater quantity than has previously been reported, and if any person reading this history knows of more, I shall be more than happy to hear of it.

Earlier, and incomplete, versions of chapters in this book were written as a series of articles for the North Eastern Express , and I am grateful to the then editor, John Richardson, for permission to re-use the material. Although I have received considerable assistance from many individuals in the course of this research, I am solely responsible for the assembly of the information. I have tried to provide as unbiased and complete an account as possible, but the interpretations are my own, and I can blame no one but myself for any errors or omissions. I am aware that others would almost certainly place greater emphasis on different aspects of the story, but I have tried to place the history of the railway plans in the context of contemporary events. For most of the lines I have followed a chronological order, although the final improvements to the Wear and Derwent Junction line occurred after the building of both the Hexham and Allendale and the Tees Valley railways. In addition, I have ventured into the world of might-have-been, to see what could have resulted if there had been some relatively minor variations in the decisions taken or the moneys available. From these considerations, I have formed the view that, had the Wear Valley Extension Railway proceeded in 1845, it almost certainly would have obtained its act and been built to become part of one the main lines between London and Glasgow, having a profound effect on the country through which it passed. None of the later planned extensions would have had the same effect, although the future of the railway in Alston might have been different.

Next page