RAILWAY EMPIRE

By the Same Author

The Canal Builders

The Canal Pioneers

The Light Railways of Great Britain and Ireland (with John Scott Morgan)

The Railway Builders

A Steam Engine Pilgrimage

Thomas Telford

THE RAILWAY EMPIRE

How the British Gave Railways to the World

Anthony Burton

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Pen & Sword Transport

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd Yorkshire - Philadelphia

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Anthony Burton, 2018

ISBN 978 1 47384 369 1

eISBN 978 1 47387 041 3

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47387 040 6

The right of Anthony Burton to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the Imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Preface

The text for this edition remains substantially unchanged apart from correcting errors that slipped through in the first edition. The big difference is the great increase in the number of illustrations which will, I hope, give the reader a broader picture of the efforts and achievements of all those who left Britain to travel the world building railways. The text is mainly concerned with civil engineering, but some of the extra illustrations have been selected to show the huge range of locomotives provided by British companies for railways overseas.

Anthony Burton

Stroud, 2017

C HAPTER O NE

Beginnings

This is a story of great adventures, of men in sola topees hacking their way through the jungles of uncharted lands. It is a tale of epic proportions, of armies of men travelling half-way round the world to shovel foreign soil into English wheelbarrows. It is also a story of high finance, of millions being raised in London for such exotic sounding enterprises as the Ferrocarril al Oeste or the Bombay, Baroda and Central Indian Railway. The crest of the latter hangs by my desk showing four Indian porters staggering up a stony path under the weight of an ornate palanquin, while a resplendent train puffs its way over a viaduct behind them, the driver leaning nonchalantly out of his cab window. Somehow it seems to sum up much of what one thinks of as the great railway empire: the old giving way to the new, the splendours of British manufacture looking down, literally and metaphorically, on the crudities of an older world. But how did all this come about? It is not difficult to imagine why British India should turn to the British engineer for help, but why should the French, the Russians, the Argentinians and the Japanese have turned in the same direction for manpower, machines and money to build their railways? It is too easy to say because Britain was first, too easy and not altogether true.

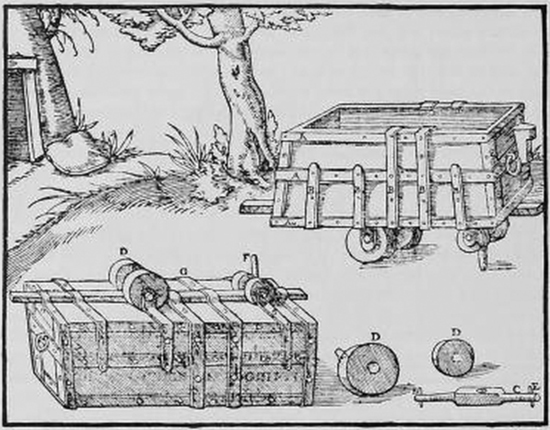

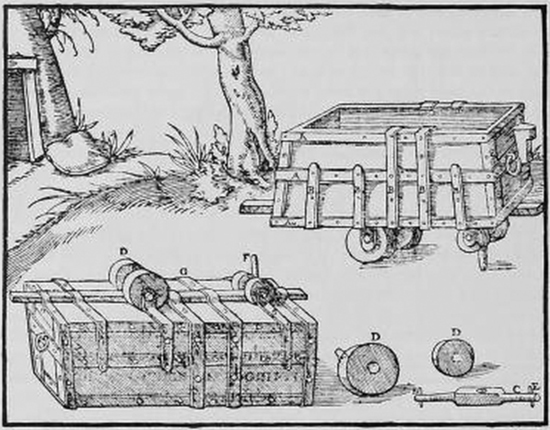

The story begins in Germany. Georg Bauer was a mining engineer who spent his life recording the best mining techniques of the age. In 1556, a year after his death, his work appeared in print, in suitably classical guise, as Agricolas De Re Metallica . It features superb woodcuts illustrating the machinery of the mines, among which scurry the miners themselves. If they seem mildly comical today, that is because they have comical associations. Walt Disney used these drawings as the basis for the costumes of the Seven Dwarfs: the first known illustration of a railway shows a truck being handled by a close relation of Happy, Sleepy and Dopey. The system Bauer showed is not strictly speaking a railway, as the wheels run on planks and the trucks are kept in place by a pin running in a groove on the track, but the elements of a railway were certainly there, half a century before there is a record of anything of the sort appearing in Britain. When that happened, however, the system was so evidently superior to the earlier model that it became generally accepted in the mining community, and even the Germans knew it as the Englischer Kohlenweg.

The earliest records of this type of railway system date from the early 1600s. Huntingdon Beaumont was both colliery owner and engineer. Some time in 1603 he laid down approximately two miles of track from the pithead of his colliery at Wollaton near Nottingham. The track was still wooden, but now there was no plank and groove; this track consisted of rails on which trucks ran with double-flanged wheels, looking very similar to ordinary pulley-wheels. There were other routes in Shropshire, but the most popular area for the new wagon-ways, as they soon became known, were the coalfields of the north-east of England. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the system was already sufficiently interesting to foreign engineers for them to wish to inspect it. Among these was a Frenchman, Monsieur Jars, who came over in 1765 and wrote a description of what he saw, entitled Voyages Metallurgiques . The nouvelles routes ran from pits near to the river bank, where the trucks could be unloaded into waiting ships that took the coal round the coast. The trucks were arranged on a gradual, steady descent so that gravity did most of the work, and they could be hauled back by horses. The system had squared-off rails, 6 or 7 inches broad by 4 or 5 inches thick, carried on parallel rows of oak sleepers, 4 to 8 inches square. The rails were held together by wooden pins, and the joints were protected by iron strips. By the time of Jars visit, there was already a movement towards replacing the old wooden wagon wheels by cast-iron. The wagons were fitted with a hinged bottom, which would be knocked open at the riverside staithes, allowing the whole load to be deposited into a chute. It was also not unknown for the flap to be jolted open in transit, dumping the coal on to the track resulting in what locals called a cold cake.

Where it all began: the first railways were used in mines in Germany. The trucks ran on a plain wooden track, with a groove down the middle. A pin on the truck engaged with the groove keeping the truck on course. This illustration comes from Agricolas De Re Metallica of 1557.

By the end of the eighteenth century the simple wagon-ways were becoming increasingly sophisticated. The improvement in iron making that began with the Darbys of Coalbrookdale made it possible to improve the track by laying a metal strip over the wood and eventually to replace the wood altogether by metal. Again many of the early experiments came in the colliery districts. In 1776 the mining engineer John Curr introduced the metal plateway to the underground workings. The rails, or plates, had an L-shaped cross-section, which held the wagon to the track. Previously, coal had been moved from the face in baskets, manhandled, or rather child-handled since most of the work went to boys and girls, along the low, narrow galleries. The plateway represented such an immense improvement, and saved so much grindingly hard labour that Curr found himself celebrated in verse with a suitably Geordie accent.