Pagebreaks of the print version

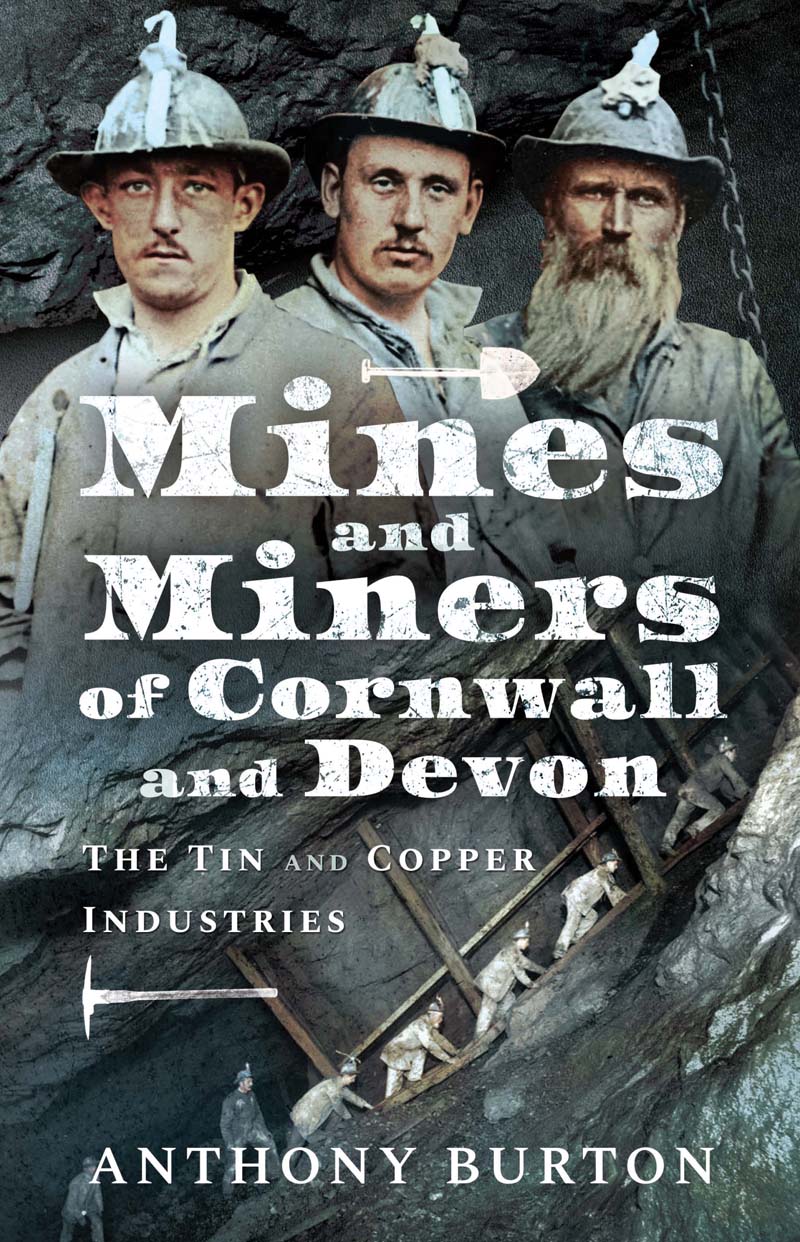

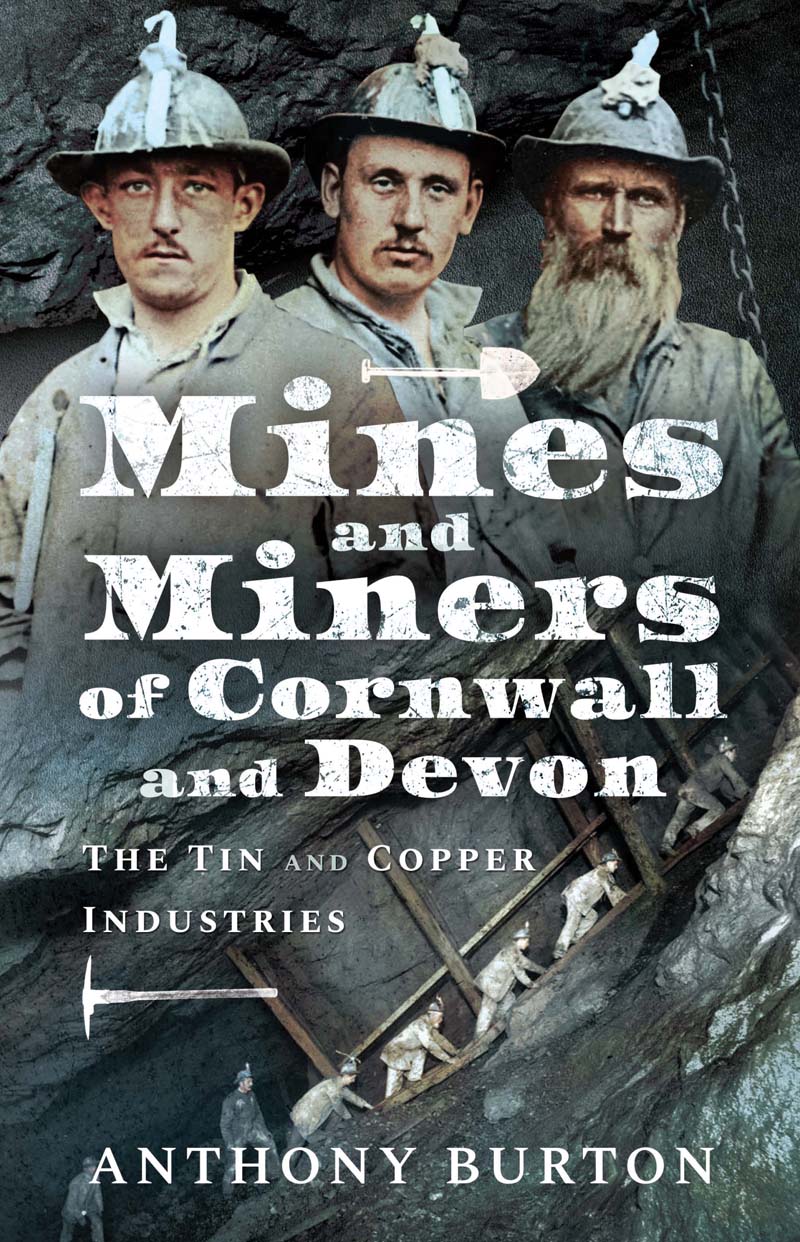

MINES AND MINERS OF CORNWALL AND

DEVON

For my wife Pip and her tin-streaming ancestors

MINES AND MINERS OF CORNWALL AND

DEVON

THE TIN AND COPPER INDUSTRIES

ANTHONY BURTON

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Pen and Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Anthony Burton, 2020

ISBN 978 1 52677 338 8

eISBN 978 1 52677 339 5

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52677 340 1

The right of Anthony Burton to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

PREFACE

Like many others not directly engaged in the industry, my interest in the mines and miners of South West England was first aroused during holidays in Cornwall. There was a particular appeal for me, as the study of the development of steam power already fascinated me and the area was vital in that it saw the development of the first practical steam engine and, a century later, the design of the first railway locomotive. And I was also intrigued by the underground world of the miner. Over the years, I have visited mines of many kinds I have crawled through Neolithic flint mines, filmed in a Roman gold mine, visited salt mines in France and many collieries, both here and in continental Europe. Talking to working miners, I have always been conscious of the pride they took in their work work most of us would rather leave to others and impressed by the resilience they and their predecessors have shown in the long struggle for safety and fair recompense for their work. All mines may seem superficially similar, but they are not, nor are all miners alike. The Cornish and their fellow workers have always been unique for their independence and noted for their skills skills that have found a welcome around the world. Theirs is a very special story, so when John Scott-Morgan asked me if I would be interested in writing their history, I did not have to think about it, but agreed instantly.

A note on units. I have used those that were current at the time, which were the old imperial units: feet and inches; pounds and ounces; pints and gallons and so forth. There are good reasons for this. For example, an engine cylinder was bored as accurately as possible to a given size, which might be 40 inches and not 101.6 centimetres. Equally, the figures quoted for the amount of water pumped from a mine in an hour would be approximated usually quite roughly to thousands of gallons; it is difficult to convey the same result in litres. A fathom is six feet and again, distances have been left in the units which the miners would have thought in every day of their lives.

I am most grateful to Tony Brooks for reading the text and making many useful suggestions and corrections. Needless to say, any remaining errors are all my own.

Anthony Burton

Stroud

Chapter 1

THE ANCIENT WORLD

No one can visit Cornwall or West Devon without at some time or other catching sight of the distinctive shape of an engine house on the horizon. Such buildings suggest, by their sheer number, that they represent a once thriving industry, which indeed they do. They might also give the impression that this was an industry born in the Industrial Revolution and the age of the steam engine and that would be quite wrong. Tin, and to a lesser extent copper, have been mined in these areas for more than 4,000 years. The minerals have, of course, been in the ground for millions of years before man even appeared on the scene. In fact, it was around 200 million years ago that molten material from the magma at the centre of the earth was forced through earlier rocks, and crystallised as it cooled. The vapours from the magma, carried with them vaporised metallic compounds, that were forced up into cracks in the granite, where they too solidified on cooling. Unlike, say, coal, that was laid down in horizontal bands, the veins of copper and tin tended to appear as near vertical veins in the rock.

Mining is probably Britains oldest industry. Even before metals were first used, the men of the New Stone Age were making tools and weapons out of flint. They found that the finest material was often under the ground in thick strata, so they began to dig down to extract it. At Grime's Graves in Norfolk, there is a huge Neolithic mine complex. If you go down one of these mines, you descend a shaft on ladders, and from the bottom of that, low, narrow tunnels lead away into the darkness. One doesnt even crawl through these, but more or less wriggle along on your stomach until the tunnel opens out into an area where the flint was excavated and even here, space is limited, with a roof scarcely more than three feet above you. The men who worked here had the simplest tools deer antlers for pickaxes and shoulder blades for shovels. We know this because, from one of these pits, one can look through to an adjoining pit, where nothing has been disturbed for over 5,000 years and there are the tools they abandoned. A Cornish miner would recognise the different elements here: the shaft; the level running away from it; and the stope where the valuable material was excavated.

Around 2500 BC, people moved out of the Stone Age and started using metal tools and weapons, by which time they had some five centuries and more of mining experience to draw on. The most important material was needed for an alloy that gave its name to this period the Bronze Age. Copper is useful for many things, but it is quite soft and easily bent. However, it was discovered that if the molten metal is mixed with tin, in proportions varying from 5 to 20 per cent, it becomes harder and stiffer. No one really knows how this important alloy came to be discovered. Indeed, we do not even know how men first hit upon the idea of heating rocks to produce metal. One theory is that stones used in hearths included some that were actually containing metal ores, and in the heat the molten metal appeared. This could only happen with metals that have a low melting point, such as tin at 232C compared with iron that has a melting point of 1,538C which is why the Bronze Age lasted for nearly 2,000 years before the technology was available for smelting iron ore.

We have no written records for this long period of our history, but archaeology can tell us a lot and provide evidence that tin was indeed being mined in the South West at this time. The excavation of Bush Barrow, a burial site near Stonehenge, revealed a range of bronze objects, including a pair of daggers that were brought from Brittany, but the materials from which they were made were from England. The barrow is dated to c.2000BC, which suggests that Cornwall and Devon already had a thriving export trade in metals at this early date. Further confirmation appeared in 1999, when two German metal detectors unearthed a find in Saxony that included the remarkable Nebra Sky Disc. The disc itself was bronze, on which were gold figures representing the sun and moon together with a few stars and lines indicating the solstices. Analysis has shown that although the copper came from Austria, the tin was from Cornwall, and the disc has been dated to around 1600BC.