Pagebreaks of the print version

THE

GREAT WESTERN SOCIETY

THE

GREAT WESTERN SOCIETY

A TALE OF ENDEAVOUR & SUCCESS

ANTHONY BURTON

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

PEN & SWORD TRANSPORT

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Anthony Burton, 2019

ISBN 978 1 52671 945 4

eISBN 978 1 52671 947 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52671 948 5

The right of Anthony Burton to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Preface

I have known Didcot Rail Centre for many years. I had visited it for pleasure many times and had even filmed there when making a BBC documentary to celebrate GWR 150. And as I lived in Oxfordshire for many years and frequently had to take the train to London, I always looked out of the window as we drew into Didcot station in the hope of seeing something on the move or an interesting item parked outside the shed. So I was delighted to be invited to write this history of the Great Western Society. But, like I suspect many visitors who come to the Centre, I had only a hazy idea about the work that had gone in to creating the experience I was enjoying. Visiting it again with the book in mind was a very different experience; exciting certainly, but the overwhelming impression was one of admiration for what has been done and is still being achieved.

Research was based in part on documentary sources I was supplied with Newsletters from the earliest days and copies of the Great Western Echo . These were invaluable but I could never have written the book without the help of the volunteers and members of the permanent staff who took the time to show me round and to sit and talk about their own particular areas of interest. I also received help from members of the Firefly Trust and the Swindon Panel Society. There are too many for me to name every individual, but I owe a special debt to Richard Croucher for organising the various visits that I made to Didcot in 2017 and 2018. I am also grateful to everyone who supplied the photos that illustrate this book the vast majority have been supplied by Frank Dumbleton and Laurence Waters. The book could not have been produced without them. Various people have read the text and offered their comments, but any errors that remain are entirely mine.

We live in an age of metric measurements, but in the days when the Great Western were building railways, locomotives and rolling stock, everything was in the older imperial measurements. I have used those measurements here, because they seem more appropriate. A locomotive might run at Didcot at a working pressure of 200 pounds per square inch, and that is what the pressure gauge will indicate not 13.8 bar. Similarly, when the engineer decreed that an engine should have 6ft drive wheels that is what he got, not 1.83 metres.

Anthony Burton

Stroud 2019

C HAPTER O NE

Why Great Western?

It perhaps seems slightly perverse to start an account of the Great Western Society by appearing to question its very existence. But it is a question worth asking because it seems there is no railway company anywhere in the world that has attracted so many supporters nor roused such enthusiasm. So, what is the answer? In fact, there is no single answer, but instead a happy combination of factors that combine to make the companys title more than a mere example of public relations hyperbole; the Western Railway was, indeed, Great.

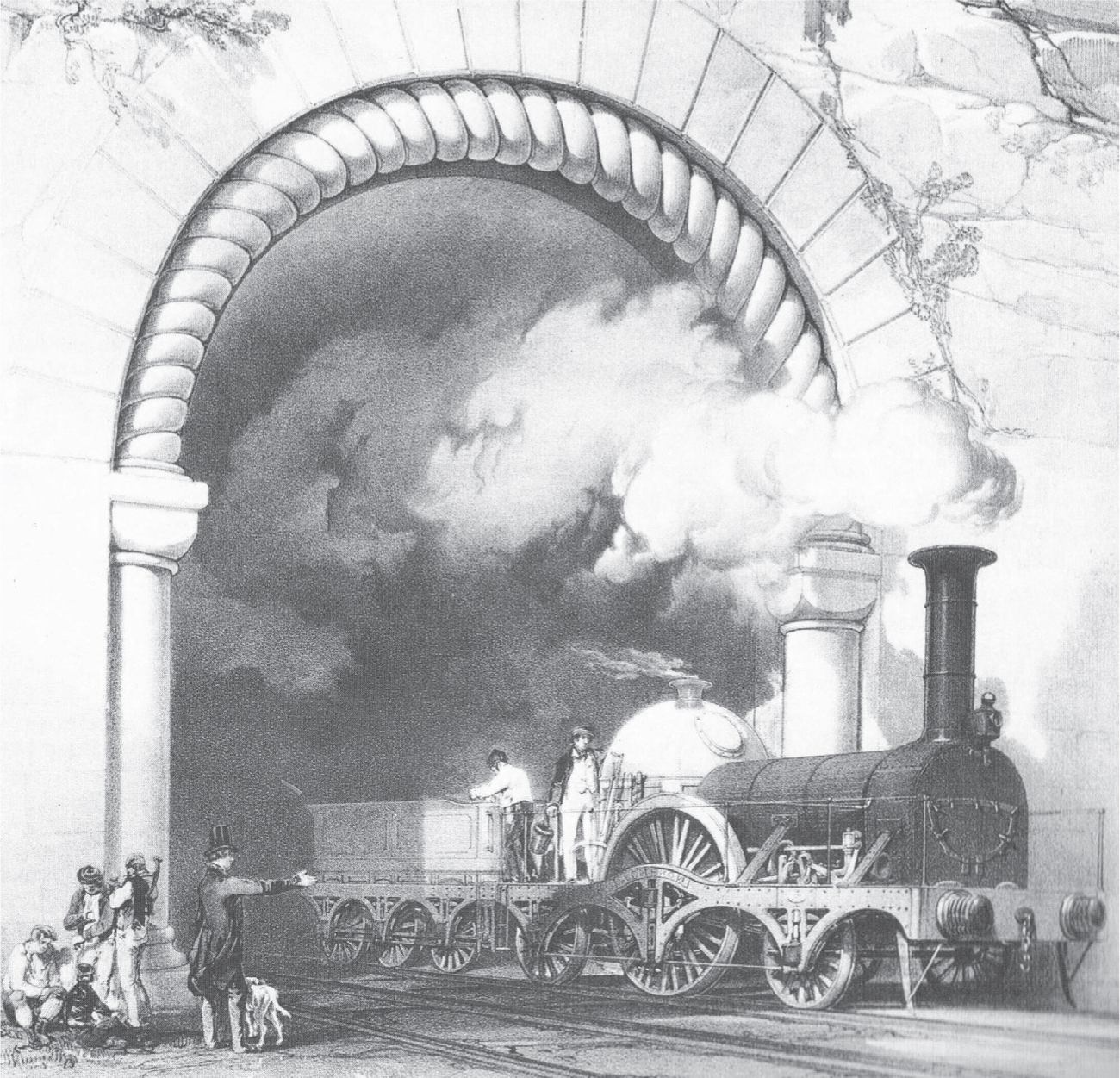

The first factor has to be the man who became the Chief Engineer responsible for planning and building the line, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. His name regularly crops up in any list of greatest Britons of all time and almost invariably he would be the only engineer to get a mention. He is an instantly recognisable figure with his stove pipe hat and big cigar but what makes him stand out from his contemporaries is the breadth of his achievements, his audacity and his absolute determination to do things his own way regardless of what the rest of the world might think. All these traits appear when we look at the Great Western.

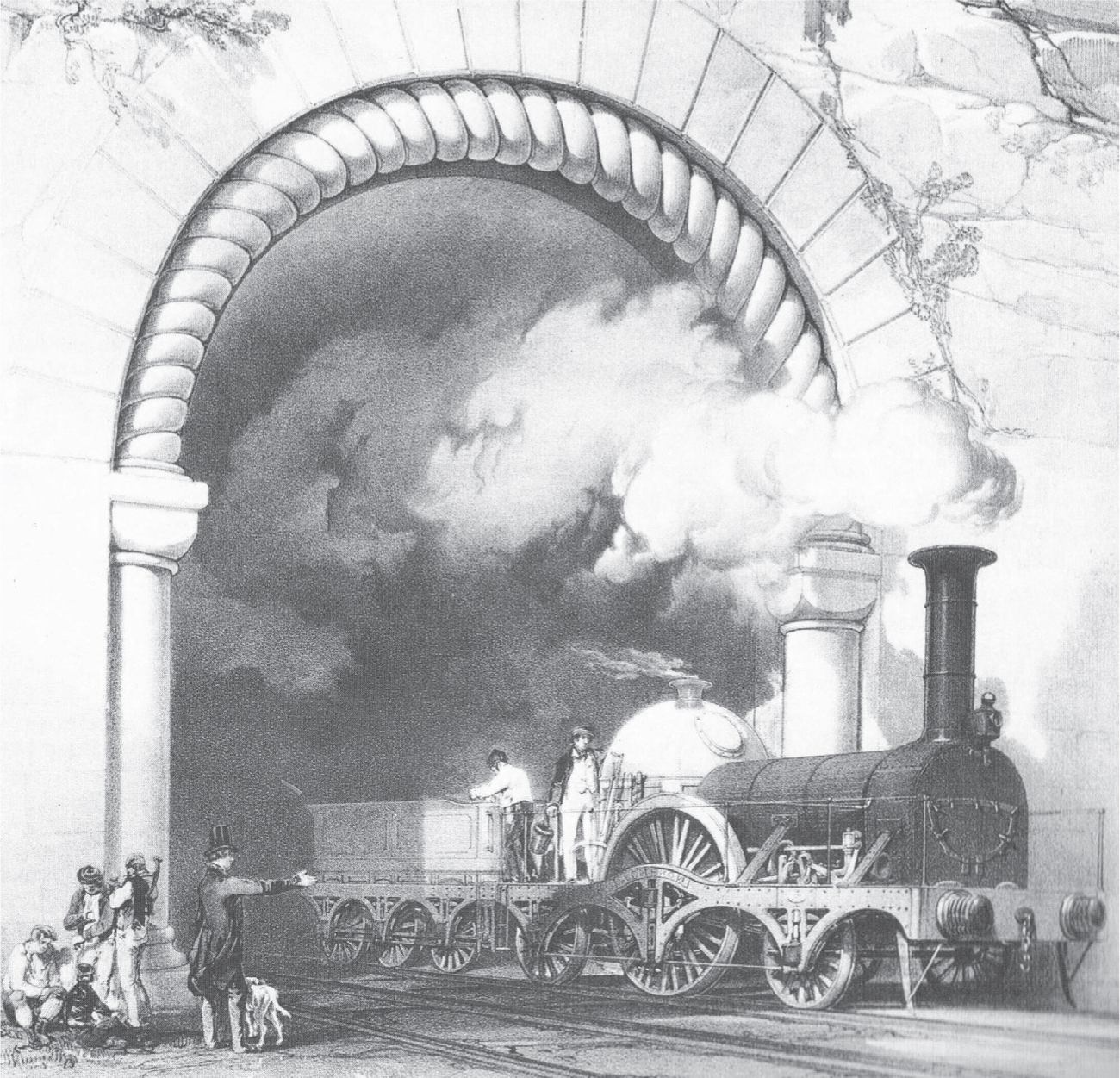

It is still astonishing to realise that when he was appointed as Chief Engineer, Brunel was still only 27 years old, and yet was quite happy, from the first, to ignore precedents and the notions of more experienced engineers. When George Stephenson first began building steam locomotives, he did so for existing colliery lines that had originally been worked by horses. When he moved on to the more important lines, the Stockton & Darlington and the first inter-city route, the Liverpool & Manchester, he simply stuck with the same gauge, which would eventually become standardised as 4ft 8in. Brunel began from a very different position, by asking a very fundamental question; what would be the best gauge to ensure fast, comfortable travel? And, of course, the answer he came up with was his broad gauge of 7ft. The way he laid out his track was also fundamentally different, as we shall see later. He was a man who made his own decisions. When a gentleman by the name of Dr Dionysus Lardner, considered one of the most eminent scientists of the day, declared that travellers would not survive a journey through the proposed tunnel at Box, he ignored him and was proved right. When other engineers declared that the flat brick arches of the bridge across the Thames at Maidenhead couldnt possibly stand, he built it anyway and it still survives to this day. Not that he got everything right. If his own ideas about locomotive construction had been allowed to prevail, the result would have been a very poor service indeed. Fortunately, he had enough sense to hire a brilliant young man called Daniel Gooch, who at once put the Great Western at the forefront of development. Brunels determination to go for the new and experimental did not always lead to triumph and few of his decisions were more disastrous than that to install the atmospheric railway when extending the route westward from Exeter. Its failure might have resulted in many companies giving their engineer the boot; but such was Brunels reputation and charisma that he was simply allowed to replace the system with a conventional railway and to continue his work of extending the Great Western Railway empire.