Pagebreaks of the print version

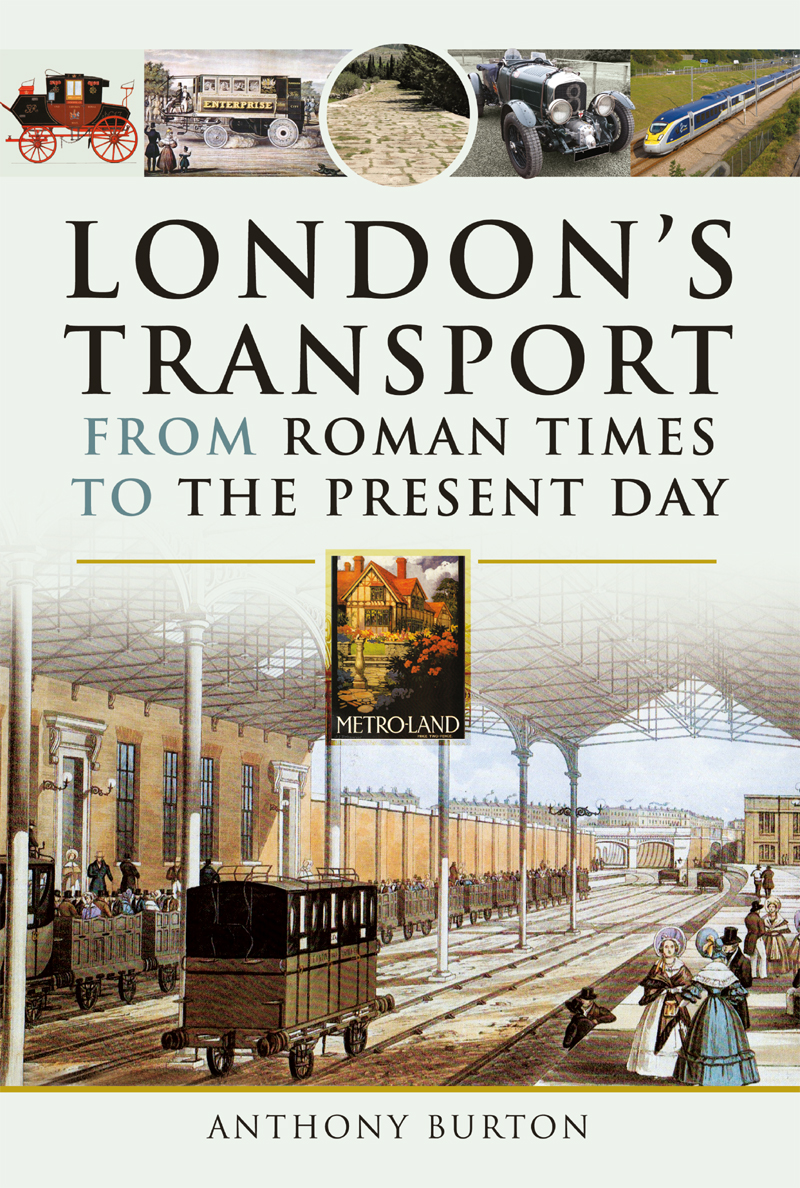

LONDONS TRANSPORT

From Roman Times to the Present Day

LONDONS TRANSPORT

From Roman Times to the Present Day

Anthony Burton

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

Pen and Sword Transport

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Anthony Burton, 2022

ISBN 978 1 39908 586 1

The right of Anthony Burton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

I dealt with water transport in London in an earlier volume Maritime London so this book will be looking at road, rail and air transport in London from the earliest times to the present day. Defining London chronologically is simple: it begins with the establishment of Londinium in the first century CE. Defining it geographically is rather more complex. For centuries, London was defined as the walled city so that, for example, Westminster was then a separate place altogether. Then, over the centuries, the city grew, swallowing up what had once been quite distinct villages, such as Hampstead, and in more recent times it has also eaten up large parts of the old counties of Essex and Middlesex. I have taken a rather pragmatic approach, basing the story largely on what we would now regard as central London, but allowing excursions further out into the suburbs as the story changes with the years.

There is another problem that always comes up with writing history, especially when it involves technology: which units do you use the ones in use at the time or the ones we officially use today? I have gone with the historical method, simply because they make sense in the context. If an engineer in the nineteenth century specified that he wanted a steam cylinder to be 24 inch diameter, he would not have asked the manufacturer to provide one at 60.96 cm. But, of course, when we come to the modern era, decimalization has changed everything, so I shall be using the units of today. The last problem is money. Again, decimalization has introduced new units, but younger readers might like to know that before that we had 20 shillings in a pound, and 12 pennies in a shilling. Values have, of course, changed dramatically, even in a few decades. Even a modern penny coin is generally regarded as much a nuisance as a valuable item to be cherished. For example, that old penny two centuries ago had roughly the purchasing power of one pound today.

C HAPTER O NE

The Beginnings

The story has a natural starting point: the foundation of Londinium, the Roman name for London, in the first century CE. This was a comparatively small settlement and had hardly had time to get organized before it was totally demolished. The trouble started with the death of the Iceni king Prasutagus, at which point the Roman rulers declared that it was their right to now claim not only his property but also that of all the nobles of his court. His widow, Boudica, was not surprisingly outraged and objected to the grabbing of all these possessions. The Roman response was to have her flogged and her daughters raped. This was sufficient for Boudica to arouse the Iceni to follow her in a war against the Romans. After initial successes, the Iceni marched on Londinium, which was then abandoned. Boudicas success was short lived and once the rebellion had been quelled, Londinium was rebuilt, this time within solid stone walls. Excavation has revealed the extent of this new city. The walls spread along the north bank of the Thames from the present sites of the Tower of London to just short of Blackfriars railway bridge: the northern edge is still remembered in the name of the street, London Wall. At about the same time, the Romans also constructed the first bridge across the river.

Londinium was now, in effect, the capital of Roman Britain, and although it has long since been built over many times, we know that its streets would have been laid out in a regular grid, in the same way as other towns had been throughout the Roman empire. The Romans were not in the habit of changing their ways just because they had arrived in a different country, so the best way of imagining how a Londinium street might have looked is to turn to the site where devastation caused a great tragedy yet preserved an amazing amount of physical remains: Pompeii. Here, we can see streets paved with large flat stones, with deep ruts cut over the years by the passage of heavily laden carts. On either side are the pavements, with substantial kerbs, mainly around 30 cm high. There are stepping stones for pedestrians to cross the roads a lot of them, far more than in other Roman cities. Why were they needed? One has to remember that all the traffic of the town was pulled by animals who, to put it delicately, were not exactly toilet trained: the stones kept Roman feet clear of the muck.

The capital was also the hub from which major roads led out to the other main Roman centres. We have given them names, such as Akeman Street and Watling Street, but we have no record of what the Romans themselves called them. Using modern place names, the main road heading south went to Canterbury, where it split off into branches to four ports Richborough, Dover, Lympne and Reculver. There was another route to the Channel port of Chichester. Heading westward, the road led to Silchester, and again divided with branches to Portchester, Exeter and Caerleon. Two routes led north: one to Chester that was then continued on to Carlisle; and the other to York, again continued on to Hadrians Wall and Corbridge. Finally, the eastern route led to Colchester. The one thing everyone thinks they know about Roman roads is that they are straight. This is not strictly true. The Roman military engineers who were responsible for surveying and building the routes took the most direct route that was possible, but they always had to take the landscape into account. Some years ago, I walked following the route of Akeman Street from Cirencester and where it reached the valley of the River Reach, the line of the ancient road was clear, running in a sweeping curve to make an easier gradient. What they did not have to worry about was getting permission from local landowners; their views were immaterial as far as the Romans were concerned.