CONTENTS

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

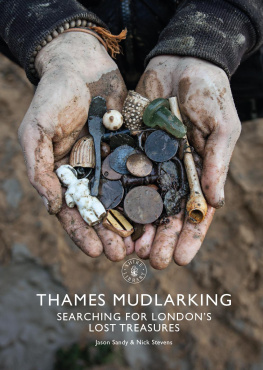

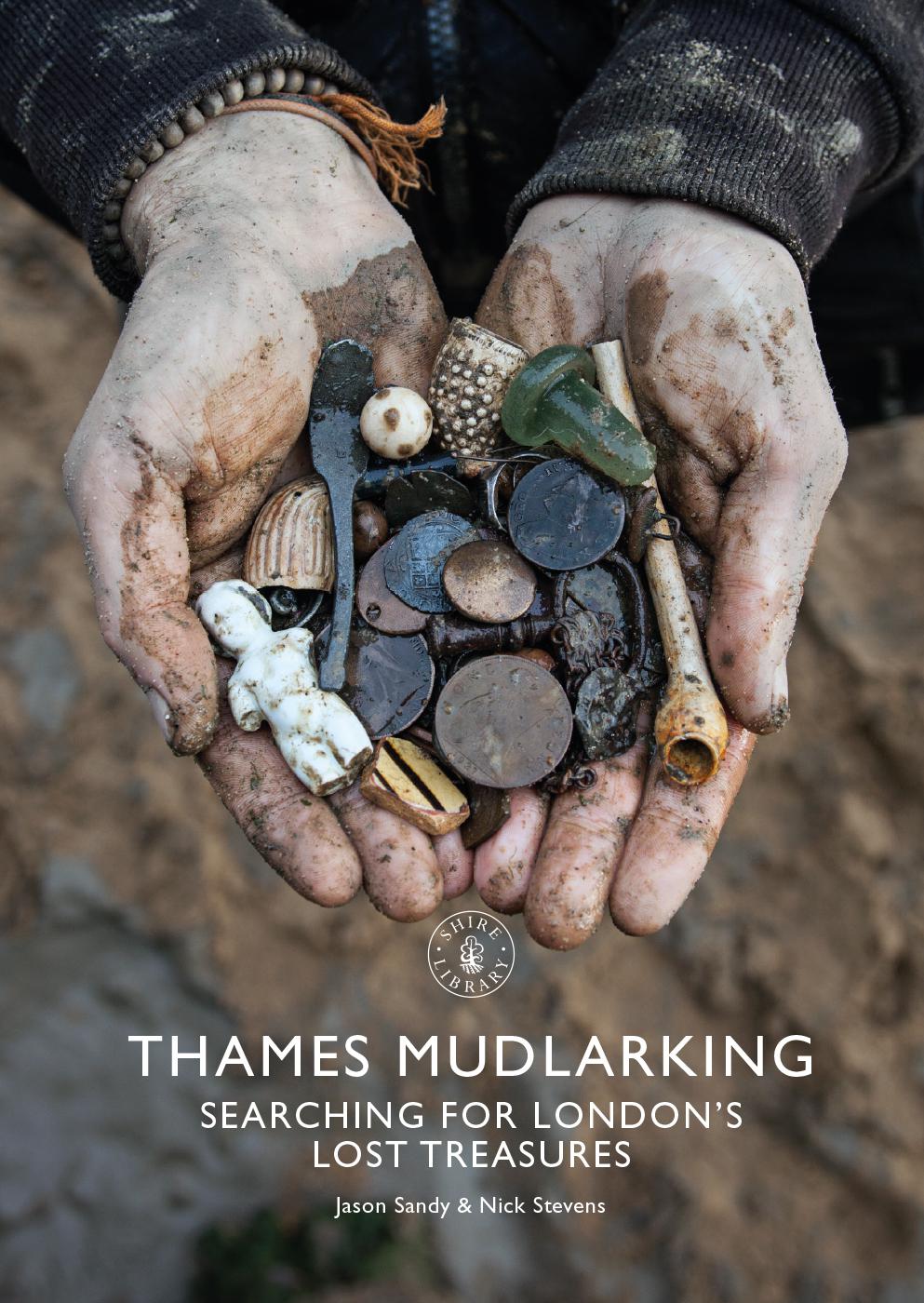

A selection of mudlarking finds. (Jason Sandy)

INTRODUCTION: MUDLARKING

Ever since man first quenched his thirst in its waters, he has left his mark o n the riverbed.

Ivor Nol Hume, Treasure in th e Thames (1956)

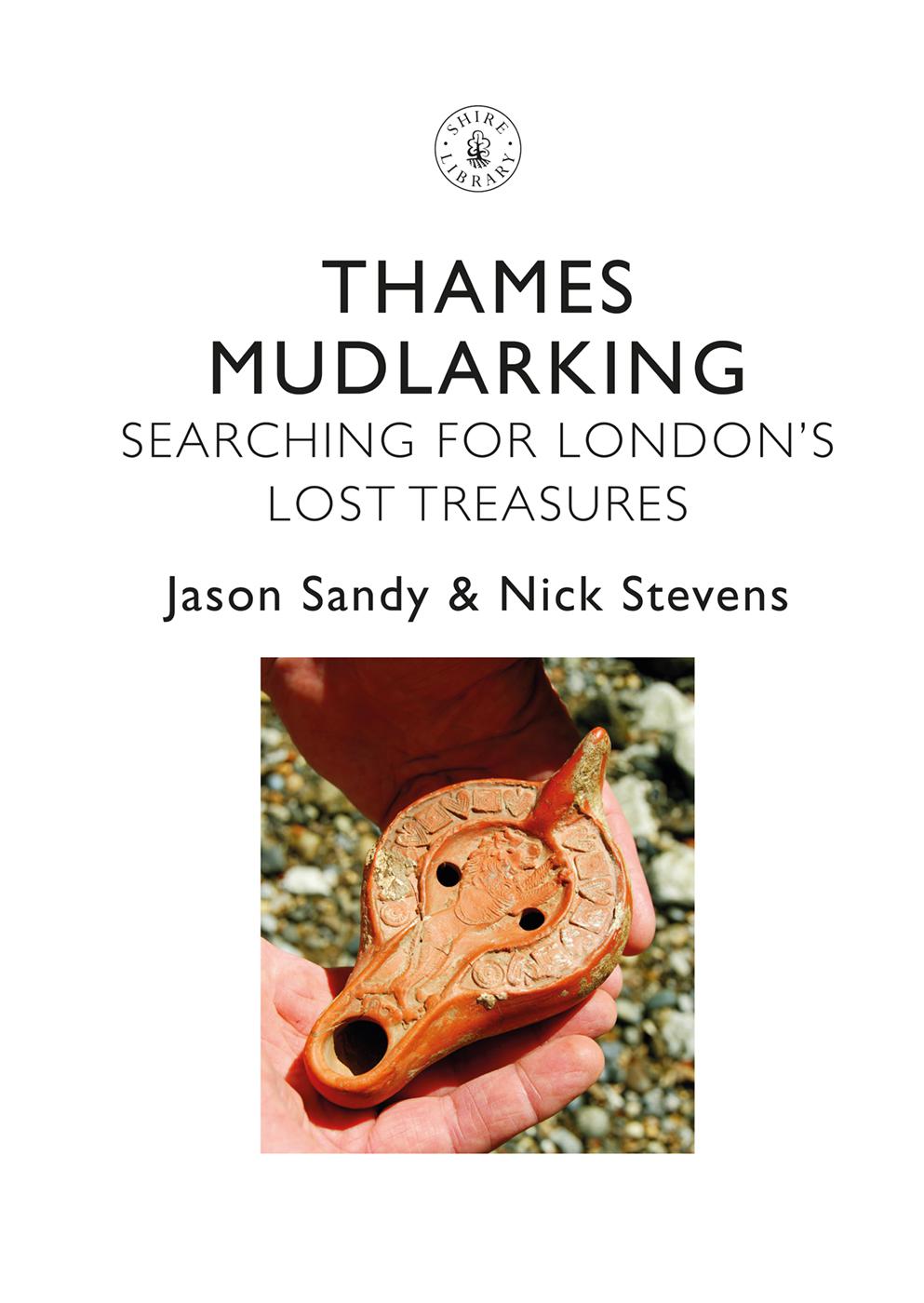

W HILE CASUALLY WALKING along the exposed foreshore of the river at low tide, mudlark Alan Suttie spotted a mysterious red object lying on the surface. As he picked it up and carefully examined the object, he couldnt believe his eyes! It was a highly decorated Roman oil lamp that had been dropped in the river around 1,700 years ago (see ). Stuart Wyatt, Finds Liaison Officer at the Museum of London, described it as one of the best fourth-century lamps to be found in the city, a rare survivor from the last days of Roman London. Extraordinary not only for its inherent beauty, it is also a rare example of a North African ceramic oil lamp from AD 300410 , depicting a running lion which symbolises Christianity. This is one of the many historically significant artefacts which have been found in the River Tham es by mudlarks.

Without the River Thames, London would not exist. Flowing through the heart of London towards the sea, the Thames was a vital transportation link between London and trading posts around the globe. When London was the largest port in the world, the congested river was filled with ships and boats of all sizes, from large ocean-going vessels to small rowboats with watermen transporting passengers from one side of the river to the other. For eleven continuous miles in London, both sides of the river were densely packed with docks, wharves, warehouses, shipbuilding yards, shipbreaking yards, fish markets, factories, breweries, slaughterhouses, taverns and public houses. The active and vibrant riverfront was home to countless watermen, lightermen, stevedores, dockworkers, sailors, merchants, fishermen, fishmongers, oyster wives, shipbuilders, shipbreaker s and mudlarks.

The Thames foreshore at low tide. (Jason Sandy)

Over the past 2,000 years of human activity along the River Thames, countless objects have been intentionally discarded or accidentally dropped in its waters. For millennia, the Thames has been an extraordinary repository of these lost objects, protected and preserved in the dense, anaerobic (ox ygen-free) mud.

A close-up of the Thames foreshore. (Jason Sandy)

Because of its close proximity to the sea, the water level of the River Thames in London fluctuates by metres with the incoming and outgoing tides, twice a day. As the murky waters of the river slowly recede, the exposed riverbed in London becomes the longest archaeological site in Britain. Only accessible at low tide for a couple of hours a day, this unique part of London is a tranquil, calm and quiet environment, completely detached from urban life above. The exposed foreshore is an enchanting and mystical place where time seems to have stopped. The surface of the intertidal zone is a strange mix of rocks, oyster shells, broken glass, bricks, terracotta tiles, animal bones, sand, gravel and mud. Hidden within this unusual terrain are lost and discarded objects, exposed by erosion and the waves of passing boats.

Jason Sandy mudlarking along the Thames foreshore. (Leon Neal/Getty Images)

Mudlarking is the act of searching the riverbed for these historical treasures. At low tide, mudlarks comb the Thames foreshore hunting for clues to the past. Its a thrilling experience to discover these artefacts because they are a tangible connection to our ancestors. We are unable to travel back in time, but by finding an object which has not been touched since it was lost hundreds or even thousands of years ago, it is possible to develop a greater understanding of the people who lived at that time. Each artefact, whether ordinary or extraordinary, tells us something unique about Lo ndons history.

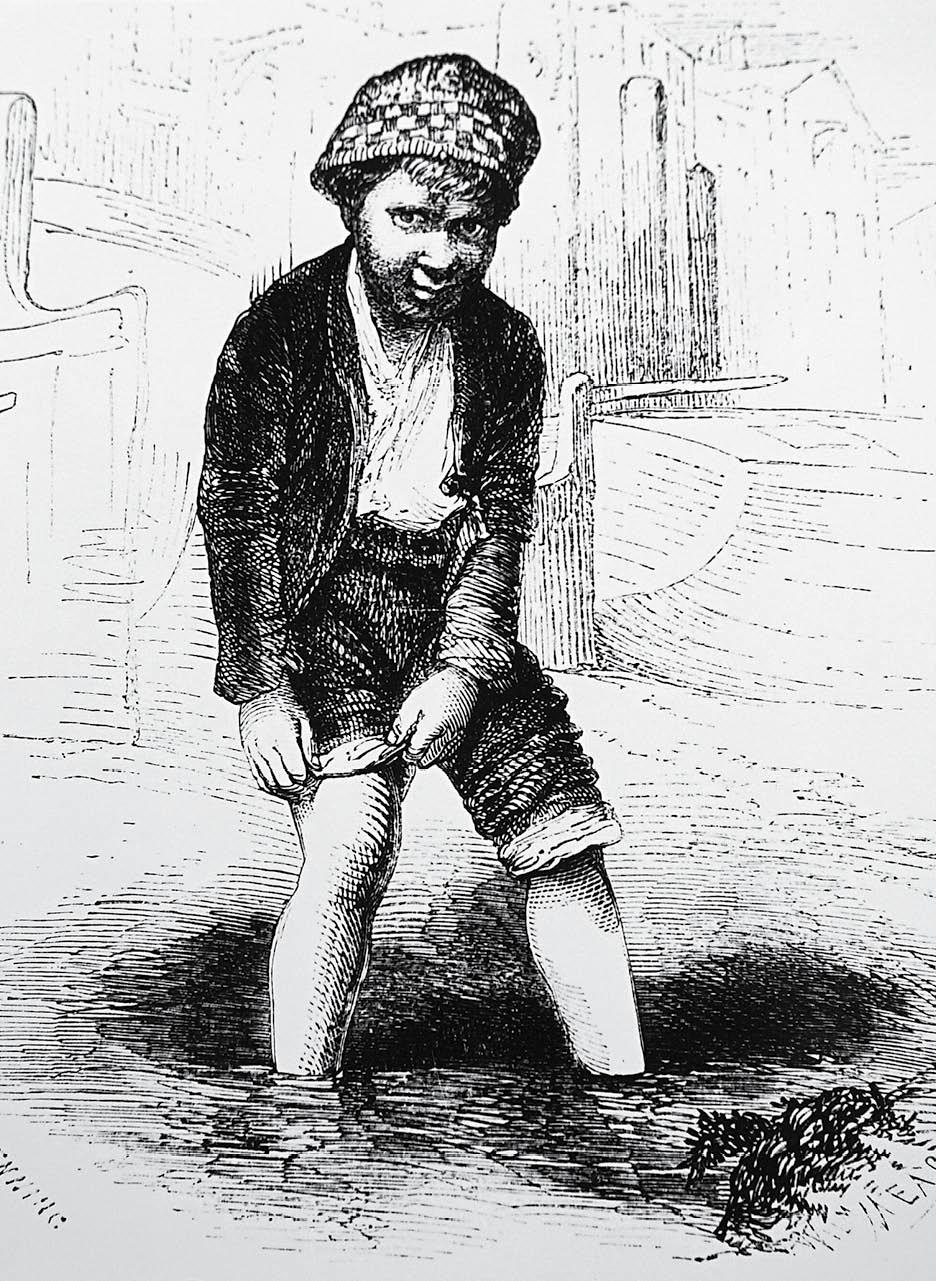

In the nineteenth century, the original Victorian mudlarks scavenged for anything on the exposed riverbed which they could sell in order to survive. They were often children, mostly boys, who braved dangerous conditions to find practical items like coal, iron, copper nails and ropes which they could sell to buy food and essentials for themselves and their families. Their income was very meagre, and they were renowned for their tattered clothes, filth and terrible stench. Out of desperation, these young children went mudlarking to survive. In the nineteenth century, they were considered among the lowest members of soc iety in London.

Henry Mayhews original mudlark. (Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

Todays mudlarks have a passionate interest in Londons rich archaeology and history. Mudlarking has become a popular hobby which gives both adults and children a unique hands-on history experience and deepens our understanding of Londons past. Equipped with a mandatory licence, mudlarks use a variety of methods to search the foreshore (some search by eye while others use a trowel, sieve or metal detector), and they have discovered and recovered an incredibly wide range of artefacts dating from prehistoric t o modern times.

Stephanie Mills mudlarking along the Thames. (Nick Stevens)

In 1980, the Society of Thames Mudlarks & Antiquarians was founded, and the members were granted a special mudlarking licence from the Port of London Authority. They formed a close relationship with the Museum of London, which recorded the extraordinary artefacts found by Society members. Through this fruitful collaboration over four decades, tens of thousands of historically important artefacts were acquired, and the museum now has one of the largest collections in the world of Medieval pilgrim and secular badges and post-Medieval pewter toys, thanks t o the mudlarks.

Mudlarks in the 1970s. (Graham duHeaume)

The museum openly acknowledges its gratitude to the mudlarks over the last forty years, whose sheer volume and variety of finds have made a very important contribution to telling the story of London. While many of the finds are small, they can alter our perspective of the past, like little pieces in a jigsaw puzzle that help to give us a bigger picture of what was going on. Stuart Wyatt explains:

Every year, interesting artefacts are constantly being discovered by mudlarks and brought to the museum. Finds from the Thames are still giving us new information and adding to the collective knowledge. These objects are continuing to enhance our understanding of Londons history and the lives of Londoners who inhabited the city over the last two millennia.