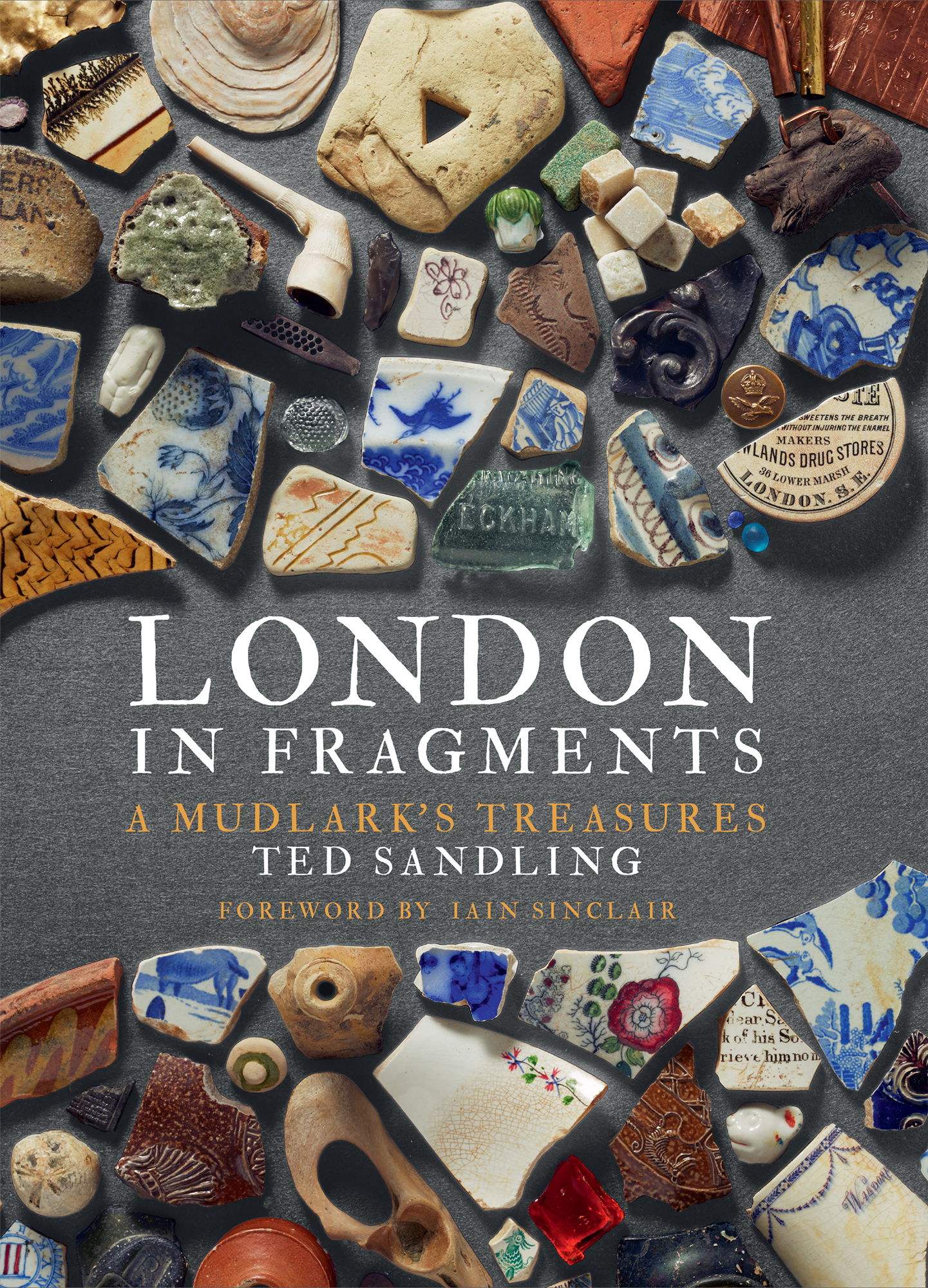

TO CLARE AND MILO

LONDON

IN FRAGMENTS

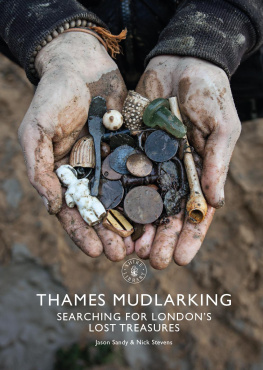

A MUDLARKS TREASURES

TED SANDLING

FOREWORD BY IAIN SINCLAIR

FOREWORD

Fired by Ted Sandlings adroitly curated account of mudlarking in crunching interstitial zones along the sole-sucking foreshore of the Thames, I came at low tide, in my heaviest boots, with a pocket of folded plastic bags, to the river steps below Tate Modern. This, as Sandling affirms, is a good place to start. Draw breath and acclimatise with a framed backdrop of heritage London. The grey whale-hump of Wrens cathedral, hedged in by never satisfied development, is emphasised today by the irregular migrainous thump of pile drivers attacking the mud. That elegant intervention, the Millennium Footbridge, is a teasing, hyper-budget reference to one of those wobbly vine cradles across the upper reaches of the Amazon. It is both an echoing catwalk of selfies and a way of avoiding the pluck and slap of the exposed beach. We have forgotten the risks that any crossing once involved. Tricky landing sites where wherries deposited Londoners with business among the brothels and theatres on the south side of the river.

Much of the approved Thames path, forever negotiating between private and public, opts for the virtual over the actual, thereby spurning the essence of what London has always been about: its river highway. That restless, sediment-heavy movement. The sound and smell of dying centuries. The pre-human gravity. To begin to understand the complexity of migration and settlement, patterns of trade, fashions in architecture, we have to learn to read the hard evidence, as it has been deposited on the foreshore. The impulse is forensic: bones, smoothed corners of brick, masonry nails, coins, relics hidden among gravel and coal bruises to tempt future detectorists and amateur historians. From these fugitive traces past lives can be assembled like novels missing vital chapters. In the golden hour, when the liquid carpet rolls back, we are free to comb and trawl without challenge, to carry home choice shards from which we can almost taste the biographies of those who were here before us. Sandlings book is the ideal companion for a days speculative mudlarking. He offers practical information and a catalogue of seductive illustrations to complement scholarship and to promote the fetish for riparian scavenging as an honourable and long-standing tradition of place.

The practice of strolling and stooping, turning over likely stones with boots poulticed in noxious slop, is one of the surviving liberties of the city. At first, conscious of being watched by tourists and loungers, mudlarks wait for the familiar shout of the orange-gillet security guard. Excuse me, sir. If I were challenged among the generic fountains, outside City Hall, for having the impertinence to record my impressions by way of a small digital device, why should I be allowed to explore the exposed rubble and rotten pilings of the Thames foreshore? But on this special morning, in the afterglow of London in Fragments, anything seems possible. I remember the charge, twenty years ago, when the poet Brian Catling wobbled down wet steps alongside London Bridge to set up a brazier, on which he melted, in a huge ladle, all the lead type of his handset book, The Stumbling Block. A molten silver stream was poured into the river. It formed itself at once into a solid ball, hissing against the affronted wavelets, before disappearing from our astonished gaze.

Sadly, no alchemised lump of poetry was discoverable in the mud below Tate Modern. Sandlings much sharper eye identified a type block at Vauxhall with enough text remaining to stand as the most perfect description of a mudlarks dreams. GOLD Handsome graved, and ... Pearls and fine lustrous Gems. The first lesson of the river is that we find what we need to find. Gnomic phrases confirm unresolved quests. Hints gleaned from London in Fragments led me to pick up objects I might otherwise have ignored. There were numerous stems of broken clay pipes, but nothing as striking as the horses hoof pipe bowl Sandling bagged on an early outing. The disposable relics of Victorian smokers, like buried whispers from the novels of Charles Dickens, hold traces of the DNA of long-dead London working men who took time to contemplate the flux of the river. Beneath the notice of professional archaeologists, the cheap clay pipes invoke the thin wands laid across the chest of the young man excavated in 1823 by William Buckland from Paviland Cave in the Gower Peninsula, the oldest ritual burial in these islands.

I picked up the neck of a green-glass bottle. The jagged lip I knew was broken by design. Here was a container for ink, originally plugged by paper not cork, and snapped from a blowpipe. Ink for an unwritten book in the secret library of the city. There is something so attractive about parts of words on china, ceramic tiles, shards of industrial jugs and bottles. For years, I have been carrying home mutilated alphabets, sentences to be fitted together. Its like an endless game of post-architectural Scrabble. On the raised beach, below the promoted collections of Tate Modern, I make my own small exhibition, starting with letters on smoky glass: & CHIC FFEE. Trade goods: chicory, coffee. Miniature histories of colonial invasion and exploitation. And I gather up Chinese blue chips of tesserae, a temple floor still to be laid out. Morning-bright colours shine in dark slurry like beds of drowned forget-me-nots.

A few days later, still high on London in Fragments, I investigated the foreshore, upstream in Battersea, close to the church in which William Blake married Catherine Boucher. This second expedition confirmed the differences that are to be revealed in every stretch of the river. In Battersea, the slipway was decorated by single shoes and trainers hung in an unstable curtain from the mooring chains. There were no broken stems of clay pipes. There were no decorated blue tiles. And the only intact bottle that I captured was embossed with elephants, snake charmers, palm trees and a boat. Closer to Walt Disney than Vishnu, said my companion, who did his best to crack the Hindi script. What we had picked up was a beer bottle, perhaps a votive gesture to the river, signalling a shift in the social demographic. The Battersea foreshore offers evidence of water ceremonies dedicated to Ganesh, from a festival held in September.

The joy of London in Fragments is that it takes us straight back to the founding myth of our city: why we are here, why we remain. The story has elements of Henry Mayhews reportage, elements of a formidable cabinet of curiosities promoted by a generous collector. There are obvious parallels with the artist Mark Dions memorable mudlarking project, Tate Thames Dig. Dion laid out a display without hierarchies or discriminations of plunder. Whatever was gathered up from the foreshore, beside Tate Britain at Millbank and Tate Modern at Bankside, could be categorised and labelled with the dignity of some august institution like the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Books dissolve in the bite of the river. But accidental junk, the jumble of vanished lives, is immortal. Ted Sandling lays out the map of his own obsessions and we become willing accomplices on an algorithmical walk that will last until the waters cover our city.