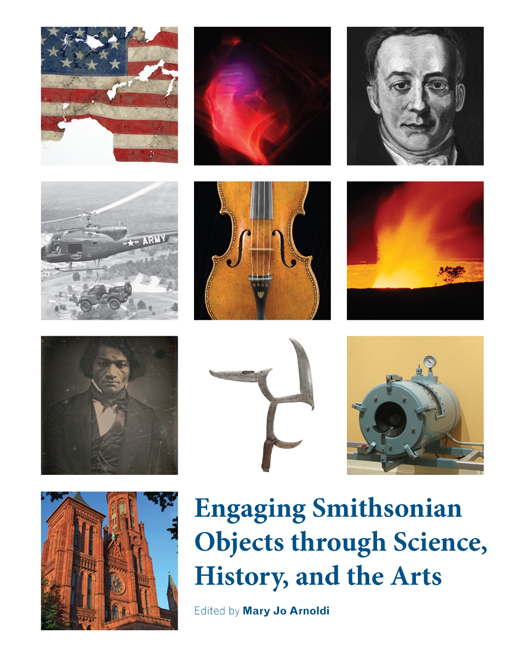

FRONTISPIECE.

The Smithsonian Institutions first building, the Castle, was designed by architect James Renwick and completed in 1855. Until 1881, it housed research and administration offices, lecture and exhibit halls, a library, laboratories, collections storage, and living quarters for the Secretary. Today, the Castle houses administrative offices and the Smithsonian Information Center. It remains an iconic symbol of the Institution. Photo by Eric Long.

Published by

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SCHOLARLY PRESS

P.O. Box 37012, MRC 957

Washington, D.C. 20013-7012

www.scholarlypress.si.edu

Compilation copyright 2016 by Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

); The Smithsonian Castle (see Frontispiece).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Engaging Smithsonian objects through science, history, and the arts / edited by Mary Jo Arnoldi.

pages cm

A Smithsonian contribution to knowledge.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-935623-16-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-935623-73-1 (ebook) 1. Material culture. 2. Museum exhibitsSocial aspects. 3. Smithsonian InstitutionExhibitions. 4. Smithsonian Material Culture Forum. I. Arnoldi, Mary Jo.

GN406.E655 2016

069--dc23

2015018885

ISBN: 978-1-935623-16-8 (print)

ISBN: 978-1-935623-73-1 (ebook)

v3.1

Contents

Mary Jo Arnoldi

Richard Stamm

David R. Hunt

Bernard Finn

Judith Zilczer

Richard Fiske

Adrienne L. Kaeppler

Gary Sturm and Bruno Frohlich

Bruno Frohlich and Gary Sturm

Roger Connor

Peter L. Jakab

S. Terry Childs

Mary Jo Arnoldi

Katherine Ott

Matthew A. White

Ann M. Shumard

Frank H. Goodyear III

Dwight Blocker Bowers

Ellen Roney Hughes

James B. Gardner

Marilyn R. London

Material Matters: Ways of Knowing Museum Objects

Mary Jo Arnoldi

The Smithsonian is the steward of the national collections numbering well over 137 million objects. These collections include many millions of natural history specimens, as well as several million art works and cultural artifacts, both handcrafted and machine made.handful of the millions of objects or collections, the 13 discussed were chosen to represent both the diversity and breadth of the Smithsonian holdings and to highlight the many different approaches and methods that constitute the ways that curators come to know museum objects.

The idea for this volume was inspired by the Smithsonian Material Culture Forum, which was founded in 1988 and is now in its 28th year. The forum brings together Smithsonian staff and fellows from across the institution and from within the disciplines of art history, anthropology, archaeology, folklore, geography, history, and the material and natural sciences in a lively exchange centered on topics related to museum objects and their display. These ongoing dialogues have worked to bridge the gap between disciplines like art history, archaeology, and the material and natural sciences, which have a longstanding tradition of studying the material properties of objects or specimens, and disciplines like anthropology, folklore, geography, and history, which, when they engage material culture, generally give priority to the analysis of the cultural and social contexts in which these objects are embedded. In addition to a discussion of objects, the forum also examines exhibition practices within the institution with an eye to how museum objects have been selected and displayed at the Smithsonian over its more than 150 year history and how, through exhibits, new and different meanings accrue to objects and collections.

During the same period when the Material Culture Forum was taking shape, the Smithsonian sponsored national and international seminars, symposia, and conferences around the study of objects and museums. These conversations included both museum curators and academics. Notable among them were the annual seminars on material culture (19881997) organized by the Smithsonian and Yale Universitys Center for American Studies; several conferences organized by the National Museum of American History on the study of material culture and the history of technology; and, from the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History, two international conferences on exhibiting and on museums and the politics of public culture.

Like the focus of the Material Culture Forum, each part in this volume begins with an object or a collection. For curators who are charged with studying, analyzing, and interpreting objects, their first encounter and engagement with To this end each of the 10 parts begins with a photograph of the featured object and a catalog record that notes its physical properties, including the objects material composition and size. The records also include information on when and under what circumstances the objects came to the collections. In each part, two paired essays expand upon these catalog entries and move out across a landscape of discovery not only to further elucidate the objects material properties but to engage their cultural and social biographies. Essays by Bowers, Connor, Childs, Finn, Frohlich and Sturm, Ott, and Stamm focus attention on the formal style and material properties of the object they study and on the technologies and the contexts of these objects production. Those by Fiske, Frohlich and Sturm, Hunt, and Childs feature the various technologies and techniques used to study objects or collections and explore how these different vantage pointsthe microscopic, the telescopic, or the kaleidoscopiccontribute to new knowledge. Zilczer, Shumard, and Sturm and Frohlich provide us with important insights about the biographies of the artists who created objects, and Arnoldi, Goodyear, Kaeppler, and Jakab tease out the nuances of the historical and social networks within which the particular objects were produced, performed, and consumed. Directing our attention to how meanings accrue to objects over time and space and how these meanings change, Arnoldi, Hughes, Ott, and White analyze the ways that exhibits of these objects shaped their interpretation, and Gardner and Fiske lay out their methodologies for collecting. Finally, Fiske and London demonstrate the roles that research collections regularly play in training students and in future scientific inquiry.

The objects that are featured in this volume include a seventeenth-century violin and several nineteenth-century objects, including a marble monument, daguerreotypes, and a hand-forged iron knife. More recent objects dating from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries include a light sculpture, a medical device, anatomical collections, a helicopter, and a movie prop, among others. Some objects enjoy an iconic status at the Smithsonian, such as the Ruby Slippers from the 1939 movie