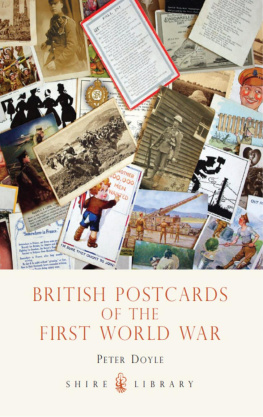

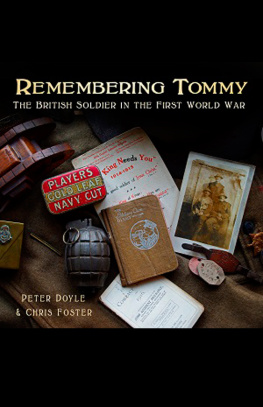

British recruiting posters issued as cigarette cards.

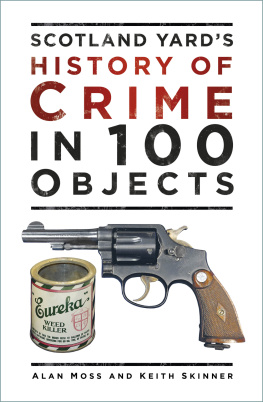

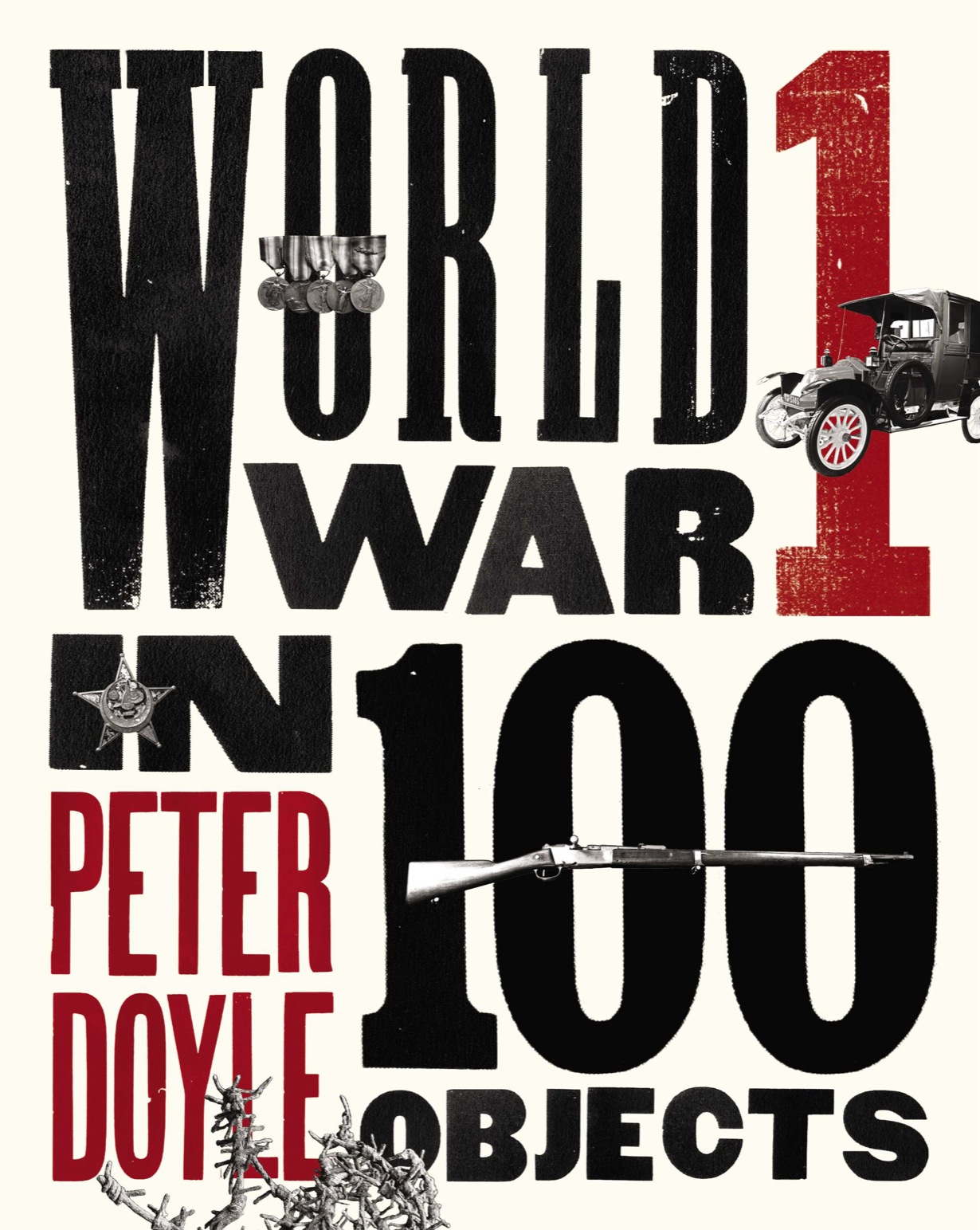

100 Objects

THE OUTCOME OF the Great War of 191418 has shaped the world we live in, yet it is difficult to understand. One hundred years after this cataclysmic episode erupted from the confines of a little problem in the Balkans, it continues to both shock and fascinate in equal measure. The war that followed it, ignited from its dying embersthough both complex and grandiose in scalecan at least be reduced and distilled into a crusade against evil, of the rights of human beings to escape bondage and repression. These concepts are more complex in the Great War, discussion of which still promotes argument and dissent.

For example, while most of us are at ease with the idea of an armada of landing craft dispatching its living cargo onto the beaches of Normandy on D-day, June 6, 1944, few of us really understand the motivations behind the landings at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915. And it is difficult for us to escape from the present and consider the past with a wholly objective viewpoint; typically, we have difficulty coming to terms with the sheer number of casualties from this terrible war. So while the Allied dead from El Alamein are around 2,350, those from the first day of the Somme are 19,240. The reason why the scale of suffering on the battlefield should be so high is still something with which people have difficulty coming to terms.

At a personal level, one of the advantages we have in considering the Second World War is that we perhaps have more sympathy with the time frame. Things seem reasonably familiar to us. With the creation of the Jazz Age came the development of modernismhouses were sleeker, their contents functional, their residents lives not a million miles away from our own. Images of London high streets in 1940 differ dramatically from those of 1910; there are fewer horses, a greater number of motor vehicles, more garish shop signs, and fewer uniformed people. And it helps that we have a direct connection with people who lived through rationing, the formation of the welfare state, the era of make do and mend, and the chirpy voices of chipper radio comedians and music hall stars. But when we peer at films of the imperial powers in the run-up to the Great War, it is difficult for us to make a direct comparison of our lives with those of our forebears. The everyday life of the average citizen seems so different, with its class structures and food and clothing that are so different to our own; the average person in the street seems so remote to us. And our direct connection with those who lived during the Great War is very nearly extinguishedthe few people still around who were alive at the time were too young to understand its significance and are now perhaps too old to recall with understanding that life, so remote 100 years on.

But the Great War has left us with a rich legacy of writing, art, music, and poetry. This legacy allows us to perceive what life was like during the period. By their nature, many of these records present a very particular view of the war, one informed by the natural antiwar reaction of that generation. Much of the writing from participants in the Great War that appeared in the fertile ten-year period after the war is disillusioned with it, distanced from its purpose, disassociated with the ideals that led people to join the forces and serve their country.

For many today, jaundiced with conflict and high ideals, the idea of mass recruitment to fight for King and Country seems alien. Seeking to understand the lives of our families, to connect with their experiences, is how many people now connect with the past that is the First World War. In many cases, their starting points are the creased photographs, the fading postcards, and the tarnished medals. In the United Kingdom, soldiers, sailors, and airmen were awarded campaign medals that, fortunately, were named. This act of naming allows the narrative of both the medal group and the person who was awarded it to be interpreted and read. Each campaign medal is essentially the same yet ultimately different. This fact, coupled with the availability of records through archives and the Internet, allows family historians to unlock the stories of their objects and the actions of their forebears.

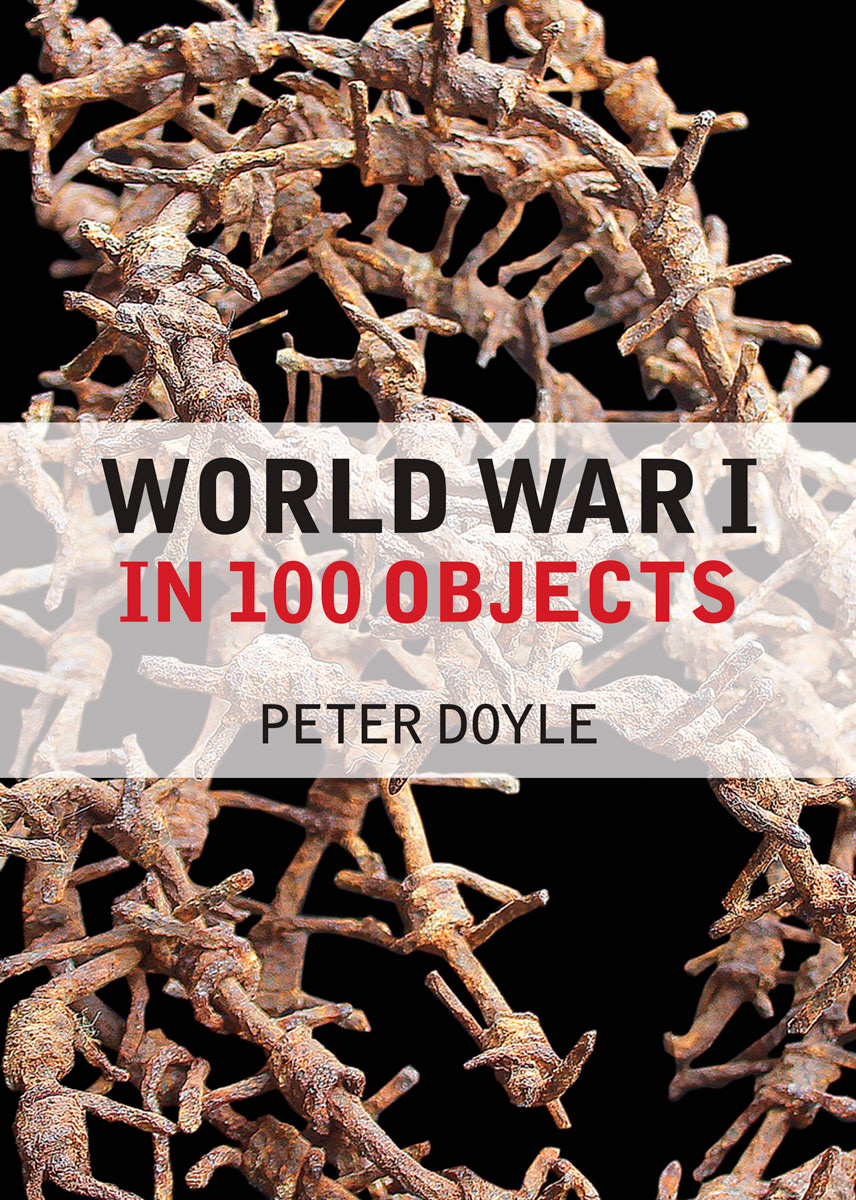

As one writer has put it, Objects hold within themselves the worlds of their creators. They represent a time capsule, a direct link with the time in which they were made. But they are also mute witnesses to events, recording devices that might allow a clearer understanding of a time or eventif only we can read them. Each object has a story, a unique narrative that is there to be interpreted, to be read. For many of the objects associated with war, that narrative is plain to see: machine guns were intended to kill, gas masks to protect. But like any story, there are subtextsthe suitability of these objects for the job at hand and the value that was placed on them by their user or captor. While objects in a pristine state might tell of storage and disengagement, others with wear relate to us that they were theresoldiers equipment with regimental numbers, spoons sharpened to take on more than one role, abandoned and excavated objects found on the battlefield. Each of these allows us to explore a narrative of their creation but also of their subsequent use.

As Nick Saunders and Paul Cornish have put it, The objects of the Great War have a curious and unique character. More than any other kind of matter they seem to exist in a seemingly infinite number of... worlds simultaneously, and so can appear as worthless trash, cherished heirloom, historical artefact, memory item or commercially valuable souvenir. The objects selected for this book fall into one or all of these categories.

The basis for the book is an examination of surviving objects and the interpretation of their individual narratives. The number of objects selected100is an arbitrary one and constraining; there are so many objects to choose from, each of which would add to the patchwork of our understanding. The objects had to be extant: on public display, in a national museum or local collection or dug from the ground from an archaeological investigation. They had to be individualin my view, it was not good enough to be genericas each individual object has its own story to relate. Scale and rarity were not significant factors. While some, like the Douaumont Ossuary or the Loos football, are unique, others, such as the Adrian helmet or Mills grenade, are common. But the discussion relates directly to the object illustrated.

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA REGISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA REGISTRADA