Contents

Guide

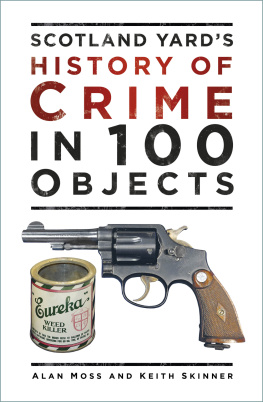

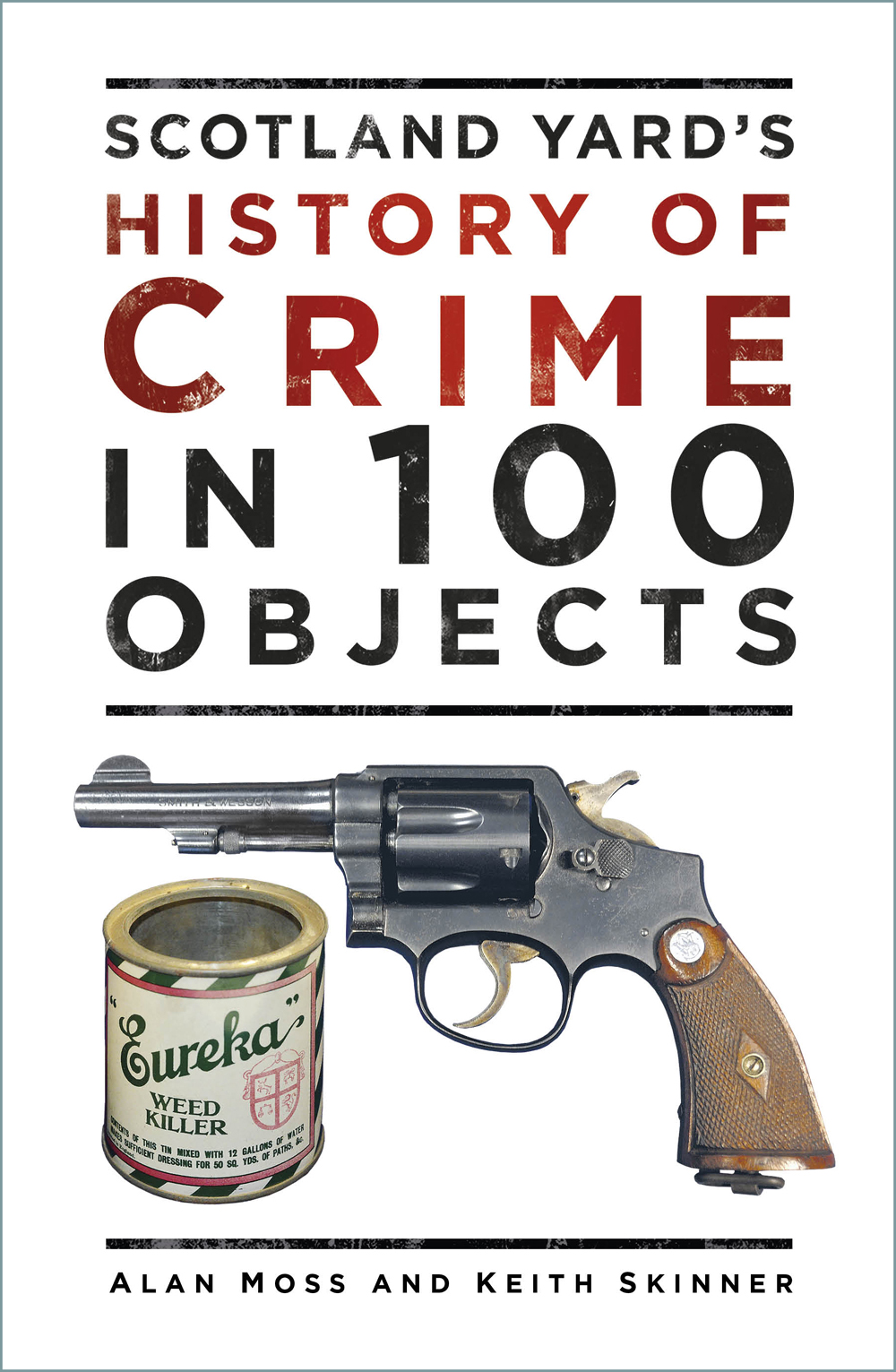

Front cover images left to right: an undamaged version of Charlotte Bryants weedkiller tin (see ).

Back cover images left to right: timing device used by the IRA (see ).

Images reproduced by kind permission of the Metropolitan Police Service.

First published 2015

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St Georges Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Alan Moss and Keith Skinner, 2015, 2022

The right of Alan Moss and Keith Skinner to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 6655 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by IMAK

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

THE OBJECTS FEATURED in this book come from Scotland Yards Crime Museum. They illustrate the history of crime and how methods of investigation have developed over the years. Some objects are courtroom sketches from the collection of William Hartley, a reporter who attended many of the high-profile trials between 1893 and 1919; his drawings give an insight into some of the characters involved. Some are everyday objects that became vital clues, whilst other objects are interesting curiosities. This book features some weapons, but the authors do not wish to risk concentrating unduly on violence. They have tried to provide a range of exhibits, and to avoid putting into the public domain any previously unknown details that might give improper inspiration. They have also taken into account Scotland Yards own judgements about what items should or should not be featured.

The Crime Museum at New Scotland Yard has accumulated an intriguing and fascinating variety of exhibits from crime scenes since the collection was established in 1875. The police have always needed to store property belonging to prisoners and evidence that might be relevant to court cases. Some of those objects could never be returned to their criminal owners when the court cases were concluded. They were sometimes examples of criminal ingenuity that illustrated the very essence of those crimes, so they were very much an educational resource for police officers.

The officer in charge of the property store, Inspector Percy Neame, and his assistant, PC Randall, started exhibiting some of the tools of the criminal trade so that their colleagues could see first-hand the housebreaking implements, forgery equipment and disguised weapons that might be found on suspects on the streets of London. As the collection expanded, the attraction of the museum increased, not only to police officers, but also to judges, lawyers, forensic scientists and many others who were intrigued by the prospect of seeing for themselves the infamous details that they had read about in newspaper accounts of the high-profile cases dealt with by Scotland Yard detectives. Sometimes the exhibits have passed through the private hands of police officers and even judges, who unofficially retained souvenirs of the famous cases in which they played a part. As with many museums, the precise circumstances of each items acquisition have not always been recorded with precise detail, but Bill Waddell, curator from 1981 to 1993, deserves great credit for establishing the modern catalogue.

The nature of some of the exhibits, and concern for the victims of crime, has always dictated that the museum could not be open to the general public. Demand for opportunities to visit the museum, even amongst police officers, has invariably outstripped the available visiting times, and this, over the years, has created a premium on the chance to see the museums contents. A journalist wrote a description of the museum in The Observer of 8 April 1877, and his comments about the appropriateness of the title Black Museum, by which the collection became known, was the first record of the name that was used for many years.

In 1889, Charles Clarkson and J. Hall Richardson described the museum in their book, Police! A General Account of the Work of the Police in England & Wales, at a time when it had not been properly organised:

There remains to be mentioned an extraordinary feature of the Convict Office. What becomes of all the property, portable or otherwise, taken from prisoners at the time of their committal? Most of it is of a trivial character, but some of it is valuable. Since 1869 it has not been forfeited to the Crown in the same way that the pence of a pauper are forfeited to the common treasury of a workhouse. Every article has to be restored to its rightful owner, and it may happen that, even after an interval of a long term of years, the rightful owner has a memory so retentive as to place a purely fictitious value upon his chattels, should any portion of them be missing or damaged. It is a strange collection of miscellaneous wares, a musty mass of odds and ends, which is stored in the cellars and garrets of the Convict Office in Scotland Yard. But every pocket-knife, bonnet-box, packing-case, or whatever it may be, has to be duly docketed, so that it may be produced when wanted. The dust of years falls upon these relics, and gives a black coating to the contents of the bins in which they are kept; they are mute witnesses that their owners are yet living, though dead to the world. Periodically all the unclaimed goods are sold, but there is always a large stock on hand, and amongst it may be noted many articles which have been produced in evidence in the course of celebrated trials.

There are five chief inspectors, but one of these, Mr Neame, is in charge of the Convict Supervision Office the Black Museum is allotted a room in the basement of the Convict Office in Great Scotland Yard, which is in reality a private house, ill adapted for the purposes required. In fact, the museum is in a cellar, and it is a collection, displayed in amateurish fashion, of relics which recall certain causes clbres. Therein is the chief interest, and perhaps the grimness of the show is not lessened by the bareness of the boards upon which the array of knives, pistols, revolvers, and criminal curios is laid out. There is no attempt at cataloguing the items, and the museum, as at present arranged, serves no useful object.

This book features 100 objects from the museum as a method of illustrating the development of crime and its detection over nearly two centuries. We hope that the stories behind these objects will create a better public understanding of the museum and about crime itself.

This updated edition has enabled us to include some exhibits that have been added to the museum in the last few years to reflect recent trends in policing. Techniques for extracting DNA from crime scenes have continued to advance. Body-worn video cameras have produced graphic evidence of the violent situations faced by police officers on the streets. Firearms can now be constructed from 3-D printers. Cybercrime equipment gives an insight into the world of criminals who can defraud victims of enormous sums of money. And yet old-fashioned policing methods, supported by CCTV, can be crucial in bringing prolific burglars like the Wimbledon Prowler to justice.