FOR CATHY

There is hardly a crime committed or a riot perpetrated but what may be referred to the intemperate use of ardent spirits and that mostly in the night time.

Dundee Police Commission, 1834

I would like to thank the following people and institutions for their help in creating this book: the staff at Inverness Library; the Highland Archive Centre in Inverness; the North Highland Archives in Wick; the A.K Bell Library in Perth; the National Archives of Scotland; the Police Museum in Glasgow; the Local History Department, Central Library, Dundee; Iain Flett and the staff of Dundee City Archives; Rhona Rodgers and Fiona Sinclair of Dundee Museum and most of all my wife, Cathy.

Contents

Chapter 1 |

Chapter 2 |

Chapter 3 |

Chapter 4 |

Chapter 5 |

Chapter 6 |

Chapter 7 |

Chapter 8 |

Chapter 9 |

Chapter 10 |

Chapter 11 |

Chapter 12 |

Chapter 13 |

Chapter 14 |

Chapter 15 |

Chapter 16 |

Chapter 17 |

Chapter 18 |

Chapter 19 |

Chapter 20 |

Chapter 21 |

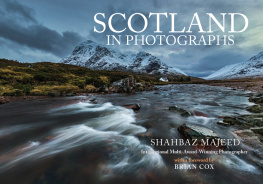

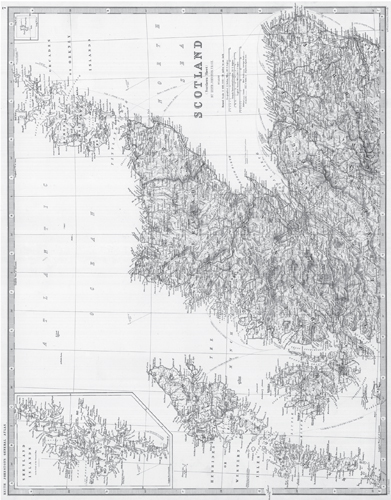

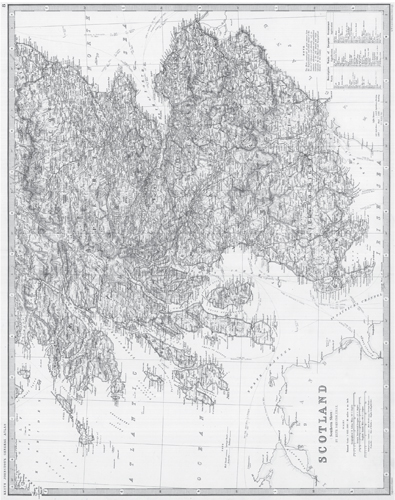

Alexander Keith Johnstones 1873 map of Scotland (published in two parts)

National Library of Scotland

Bloody Scotland continues my series of nineteenth-century true crime books that began with A Sink of Atrocity and continued with Glasgow: The Real Mean City; Whisky Wars, Riots and Murder and Fishermen, Randies and Fraudsters. It is not in any sense an academic book, although the information is as factual as possible and the events are as accurate as can be ascertained, given the weaknesses and discrepancies of evidence given by diverse people in the tense atmosphere of a court of law.

In the main, Bloody Scotland tries to avoid those crimes that have already been well documented, but tells of others that history has hidden. For example, the mass murders of Burke and Hare are not included, as they have been extensively written about elsewhere, while I have delved deeper into the Madeleine Smith poisoning case featured in Glasgow: The Real Mean City, the Ardlamont case introduced in Whisky Wars and the Dunecht mystery included in Fishermen, Randies and Fraudsters. Many of the murders, robberies and events were perpetrated in locations outwith the major Scottish population centres, hence their absence from more mainstream histories.

Although Bloody Scotland is full of horrors, it only scratches the surface of what is a massive subject. The selection process was long and painful, and for every crime included, 100 have been considered and discarded. This book is a sequence of snapshots of life in the underworld of nineteenth-century Scotland. It is intended to entertain as well as to unveil the reality of the seething cauldron of unrest, dishonesty and downright evil that sheltered behind the Brigadoon facade that many believe was the face of nineteenth-century Scotland.

The presentation method is thematic rather than chronological or geographical. There are chapters on different types of crime, such as assault and robbery, and on aspects of life that were peculiar to the period and attracted criminal behaviour, such as the railway navigators and body-snatching. However, where a story was sufficiently complex or considered to be interesting on its own, it has been granted a standalone chapter, such as the siege of John Street in Dundee.

While some people may view Scotland as a romantic land of bens and glens, or a nation where nothing much happened, this book may be a revelation. For the people who survived day by day with the constant threat of highway robbery, rioting navvies, brutal murders and clever thieves, life was often hard. If Bloody Scotland tears down only a corner of the curtain erected by false history, it has achieved its purpose.

Malcolm Archibald, Moray, 2014

Scotland is a small country at the north-western periphery of Europe. She has a ninety-six-mile land boundary with England, but otherwise is surrounded by thousands of square miles of ocean. This near isolation has helped create a nation like no other. The coastal people lived by the sea and on the sea, while the Borderers in the deep south of the country had to endure centuries of invasion and spoliation by English armies and bands of reivers. For the best part of a thousand years the Scottish nation stood in independence, repelling all attempts at foreign conquest with a grinding determination that formed a character noted for stubborn pride and taciturnity. Throughout the Middle Ages, every town and city lived with the constant possibility of destruction by an enemy, be that an English army from the south or an eruption of the Gaelic clans of the north and west. It may have been the constant preoccupation with imminent conflict that formed a people who lived with the spear to hand and a readiness to decide quarrels by quick violence.

Internal demographics and geography helped create a nation split into three distinct sections: the Southern Uplands, where the riding surnames of the Borders acted as a barrier to invasion from the south; the central Lowlands, from where urban Scots traded with Europe and created cities; and the Highlands, with their ancient Gaelic culture and links with Ireland. When the northern isles of Orkney and Shetland became part of Scotland in the fifteenth century, the nation was complete.

All these areas had their own unique history, as well as sharing that of Scotland as a whole, and they created their own historic crime. The Borderers were renowned for reiving and family feuds; they brought the word blackmail into the language. The cities could be powder kegs with Daniel Defoe the novelist believing that if the Edinburgh mob had discovered that he was an English spy they would have torn him to pieces while the Highlands were known for clan warfare and cattle theft. With such a bright history, it is not surprising that by the nineteenth century Scottish crime should be widespread, diverse and endlessly fascinating.

That century was a time of immense change that left no part of Scotland unaltered. The notorious Highland Clearances wiped out scores of communities, destroyed clachans that had endured for centuries and drove the indigenous peoples from glens they had inhabited since the memory of man. They were also instrumental in introducing new farming practices into the Highlands, a process that created its own resentments. The transport revolution altered the countryside of the Highlands and Lowlands, as railways thrust from town to town. While pickpockets haunted the stations, travellers shared the carriages with professional gamblers and the occasional sexual predator. Criminals also escaped by rail, but the formation of the railway police helped bring the balance back in favour of law and order.

Road transport also altered throughout the century, with the massive improvement of road surfacing and an increase in travel. Throughout the century thieves and robbers escaped in gigs and stagecoaches, but highway robbery was much more common in the early decades, when roads were poor and speeds slower. Sea transport altered dramatically, with steam replacing sail power.As ships increased in size, the bulk of sea transport shifted to the larger ports. However, there was crime at sea throughout the century, from brutal murder to smuggling, illegal fishing and even piracy. Jack ashore could be troublesome at times, and the dock areas of Scottish cities and towns supported their quota of seedy, raucous pubs, low lodging houses and brothels that were often a front for pickpockets, muggers and other crime.

Next page