FOR CATHY

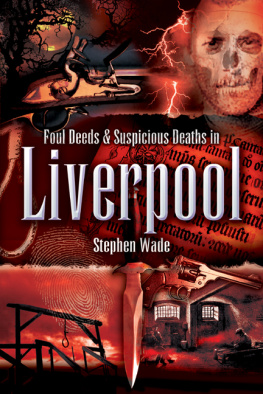

I would like to thank the following organisations and people: the Museum of Liverpool, Liverpool Central Library and Archives, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Lydia Nowak, Production Editor at Black & White, for patiently correcting all my mistakes and Cathy, my wife, for enduring my pre-occupation with crime in yet another Victorian city.

Contents

I have visited eight kingdoms on the continent within one year, and in no city or town have I witnessed such scenes of immorality and vice as are daily and nightly to be seen in Liverpool.

Traveller, Liverpool Mercury, July 1861

Courtesy of Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries.

My great-grandfather, William Michie, was a policeman in Liverpool at the time of the First World War and immediately afterwards. He lived in Toxteth, where my grandmother was born. In common with many others, he was an incomer, as his family originated in Aberdeenshire in Scotland. My grandmother returned to Aberdeenshire when she was a teenager and the family connection with Liverpool ended, although she remained a staunch Everton supporter all her life and at times of excitement or stress could break out into broad Scouse.

As a seaman, my father knew the city well. He sailed from here on many occasions during the Second World War and after. My own first visit to Liverpool was in October 1977, when Scotland played Wales at Anfield in a World Cup qualifier. Scotland won, thanks to Don Masson and Kenny Dalglish and a colour-blind referee who could not tell whose arm struck the ball that resulted in a Scottish penalty. I enjoyed that visit to Liverpool, apart from the score, and remember the bustle and pace of the city well. I also remember the friendliness of the people. That memory remained with me, so when Black & White Publishing asked me to write a book about nineteenth-century crime in the city, it was with great pleasure that I undertook the task.

This book is the result. It is in no way academic, instead it is intended to give a sample of the variety of crimes within the city and highlight some of the most interesting or most important. It was a labour of love more than pure labour, with the major problem being what to leave out. Nineteenth-century Liverpool was indeed an interesting place in which to live.

Malcolm Archibald

In the nineteenth century, Liverpool was Europes western gateway to the world and Irelands entry port to England. It was one of the worlds greatest port cities, with the 1715 Old Dock being the worlds first enclosed commercial dock, but only the forerunner of over seven miles of docks that ran along the River Mersey. By the end of the nineteenth century, Liverpools docks were granite-built and the most modern and functional in the world. Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick, commented that he made:

sundry excursions to the neighbouring docks, for I never tired of admiring them [] having seen only the miserable wooden wharves and slip-shod, shambling piers of New York [] these mighty docks filled my young mind with wonder.

From here the busy packet ships crossed to New York and Boston, the slave ships to Africa and the Caribbean, the emigrant ships to North America, the immigrant ships from Ireland, the ferries to various ports of western Britain and the trading ships to every corner of the known world. Trade was the life-blood of Britain and much of it passed through the port of Liverpool. The city was a constant buzz of movement, of people passing through, of carts and railway trains, of visitors and hopeful emigrants, of bewildered immigrants and tired dock workers, of seamen and merchants, lodging housekeepers and lonely, waiting wives, of desperate poverty and incredible wealth co-existing side by side in a hodgepodge of excitement and chaos that typified all that was best and worst in the Victorian world.

It is no wonder then that ships and their seamen were often central to crime in Liverpool. There were murders involving nautical wives, muggings of seamen, the disgusting crimps who exploited newly-arrived sailors, prostitutes who preyed on them and needed them to survive, drunken seamen causing trouble and thefts from ships in harbour. But Liverpool crime extended far beyond the dockland areas. In common with every nineteenth-century city there were atrocious murders and clever robberies, but Liverpool also experienced a bank robbery that ended in a manhunt as far as France, terrible teenage gangs and youths who burned a reformatory ship.

The second influence on Liverpools crime, and one that was also associated with the sea, was the influx of Irish. In the nineteenth century, Ireland was in a state of flux, with an elite who seemed to feel superior to the bulk of the population and the differences between a Protestant minority and Roman Catholic majority. There were constant religious and social troubles that the immigrants often brought to Liverpool with them, and the Orange Lodges tended to provoke confrontations and violence on their marches through the streets of Liverpool.

The combination of religious disputes and poverty had an effect on the Irish communities in Liverpool. It took time for them to assimilate and often they polarised into rival factions as they continued the feuds that they had carried with them across the Irish Sea. Add to that the normal tensions that created problems within any nineteenth-century community sprinkle on a military garrison who could occasionally drink too much and add the occasional terrorist bomb and Liverpool could be a lively place indeed, particularly after dark. As in every urban centre of the time, the better off left the town centre to more affluent areas of the suburbs, away from the congestion, dirt and noise. The suburbs had larger houses behind secure garden walls, but the outskirts and environs held their own dangers.

The countryside may have held happy folk memories of more apparently peaceful times, but it held its own danger. Poachers and highwaymen haunted the fields and hedgerows, and for a while the roads between Liverpool and St Helens were infested with a predatory gang known as the Long Hundred, while even places with idyllic names such as Knotty Ash could be targeted by thieves. Nowhere was safe in the days when Victoria sat on the throne and the police were learning their business through hard experience and constant striving.

1

Liverpool is undoubtedly one of the worlds greatest port cities. In the nineteenth century its location on the west coast of the most industrialised nation in the world, facing Ireland and with easy access to the Atlantic and North America, made it a natural jumping-off point for both trade and emigration. By British standards it is not an ancient city, with most of its growth being in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, but its roots go back to the Middle Ages. It was based around an agricultural settlement called Lytherpul that existed before the thirteenth century, at a time when the area was a hodgepodge of patched bogland and scattered woods, with the River Mersey a blue background and the westerly wind raising great surf rollers on the coast. This would be a wild area with wind and weather dictating the pattern of rural life and poverty guaranteed every winter.

Next page