FOR CATHY

I would like to thank the following people for their help and guidance while I was researching and writing this manuscript: The staff of Local History Department, Central Library, Dundee; Iain Flett, Richard Cullen and Angela Lockie of Dundee City Archives; Rhona Rodgers, Ruth Neave and Christina Donald of Barrack Street Collection Unit, McManus Galleries, Dundee; Kristen Susienka of Black & White Publishing, for her patience and skill during the editing process and, most important of all, my wife Cathy.

Dundee, the palace of Scotch blackguardism, unless perhaps Paisley be

entitled to contest this honour with it.

Dundee, certainly now, and for many years past, the most blackguard place

in Scotland.

Dundee, a sink of atrocity, which no moral flushing seems capable of cleansing.

A Dundee criminal, especially if a lady, may be known, without any

evidence of character, by the intensity of the crime, the audacious bar air,

and the parting curses. What a set of she-devils were before us!

Henry, Lord Cockburn, Circuit Journeys

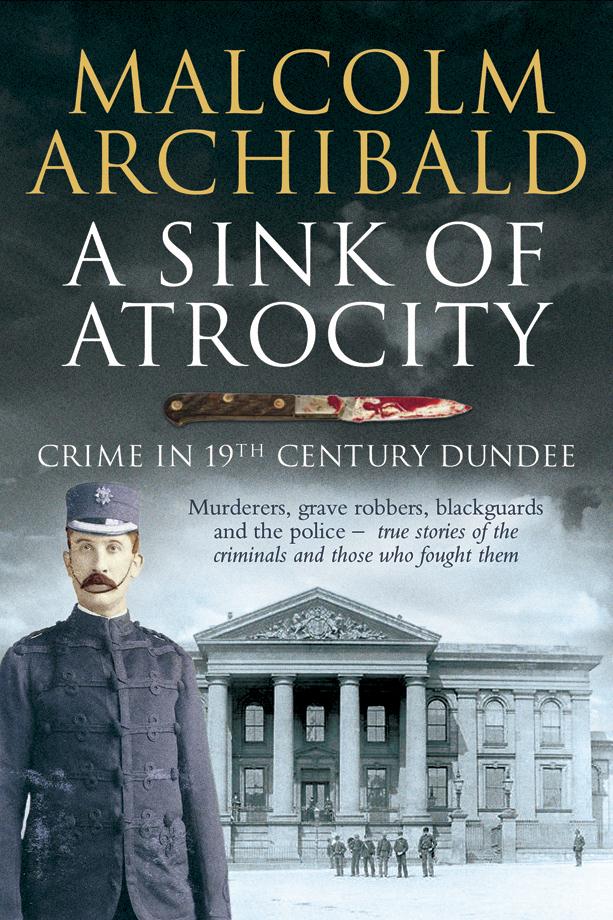

A Sink of Atrocity

When Circuit Journeys was first published in 1888, the reading public was able to see the thoughts and experiences of Henry, Lord Cockburn during the seventeen years he worked as a Circuit judge. In this impressively readable tome, Lord Cockburn both praised and condemned the people he met and the places to which he travelled. While some towns earned plaudits, Dundee was treated with nothing but condemnation. Cockburns comments bear some repetition: Dundee, the palace of Scotch blackguardism, he wrote, unless perhaps Paisley be entitled to contest this honour with it. And again, Dundee, certainly now, and for many years past, the most blackguard place in Scotland.

After a brief verbal tour of the Fife and Angus district, Cockburn returned to vilify Dundee a third time: Dundee a sink of atrocity, which no moral flushing seems capable of cleansing. A Dundee criminal, especially if a lady, may be known, without any evidence of character, by the intensity of the crime, the audacious bar air, and the parting curses. What a set of she-devils were before us!

Lord Cockburns statements influenced the writing of this book. If a judge, with all his experience of crime in its worst, most sordid, saddest and most wicked forms, thought so harshly about Dundee, the town must indeed have been a grim place. I decided to investigate further. It took only a brief glance at contemporary and near-contemporary accounts to realise that others also painted Dundee in negative colours, and sometimes they were disappointingly close to Cockburns opinion. For instance, there was Philetus, writing in the Dundee Magazine in 1799, who stated that Vice, manufactures and population kept a steady jog trot together. By making this statement, Philetus seems to blame the rise in manufacturing concurrent with urban industrialisation for a growing crime rate; but Dundee had experienced the occasional bout of law-breaking before manufacturing dominated the town. For example, according to Christopher Whatley et al. in The Life and Times of Dundee, in 1720, John Brunton, deacon of the Weavers Incorporation, led a mob to sack a merchants house and loot food from a vessel in harbour. In the absence of a police force, the authorities sent a body of military from Perth to quell the troubles and one man died and others were arrested before peace was restored.

However, mob rule was rare, and was perhaps an indication of hunger-politics more than criminal intent. By the nineteenth century and the time of Henry Cockburn, Dundee was a rapidly-industrialising town, fast becoming a city, with all the vices and horrors that were attached. In its own way Dundee was a microcosm of the period, and as such is worth investigating.

When I first envisaged this book I had a notion of an academic work with every fact referenced and tables of statistics to guide the reader. But the more I researched the more I realised that, while such an approach might appeal to a limited number of intellectuals, it would more likely repel the majority of readers. It would also litter each page with little numbers that would make reading difficult. Accordingly, I altered the approach to make the contents more accessible. This book was not written to prove an argument but to paint a picture, to try and explain not why Dundee was what it was, but how it felt to be there in the nineteenth century.

Although this book is about crime in nineteenth-century Dundee, it is equally about the people: how they coped with their environment and how they acted and reacted to the trials and stresses of life. It is about the pickpockets and footpads, the husband-beaters and vitriol-throwers, the murderers and thieves, the rioters and rapists, the mill girls and seamen, merchants and prostitutes, fish sellers and masons; it is about the people who occupied the tenements and villas and whose often-raucous voices filled the streets. Some of the incidents are tragic, others are sordid, some show elements of chilling brutality, others a sense of social justice that is humbling in these more selfish times. Often one can feel sympathy with those forced into desperate acts, but sometimes there is a sensation of creeping horror that such people exist in the same sphere as the rest of us.

Researching this book was an interesting procedure in itself and involved many hours in the libraries and archives of Dundee and Edinburgh. Dundee is fortunate that the archives hold the Police Board Minutes, while the local press filled in many details that were missing elsewhere. It was sometimes frustrating that many perpetrators were mentioned only by their surname, but that seemed to be the style of the period. However, that anomaly was counterbalanced by the double naming of married women. In Scotland, women could keep their maiden names even after marriage, which is why they were frequently referred to as, for example, Mary Brown or Smith. For the sake of clarity, this book will refer to married women solely by their married name.

The book has a simple format: sixteen chapters dealing with various forms of crime or crime prevention. Some chapters deal with a type of crime or a historical period, others are more specific. What will become apparent is that while some crimes are very much fixed in the past, others are recognisable today. In Scotland, grave-robbing and infanticide are hopefully confined to history, but theft and drunken behaviour are probably as common in the twenty-first century as they were in the early nineteenth. It is perhaps encouraging to learn that crimes we consider as products of modern life were known 150 or 200 years ago; child abuse, assault and brawls are not creations of the media, but were part and parcel of life for our ancestors as much as for ourselves. The nature of people does not change despite advances in technology.

Throughout the book I have not attempted to either prove or disprove the words of Lord Cockburn. That I will leave to the reader, basing his or her answer on the evidence presented in the following pages.

There is only one piece of advice: Keep your doors and windows locked.

Malcolm Archibald

Dundee and Moray, 2012

Trade was vital to Dundee: trade with the landward farmers who grew the produce that fed the population, coast-wise trade with the other towns and cities of the British Isles and overseas trade that imported raw produce which Dundee converted to sellable goods. At no time was the importance of trade more apparent than in the nineteenth century, when Dundee expanded from a small town into an industrial powerhouse that was the world capital of jute, a major linen manufacturer, the largest whaling port in Europe and a shipbuilding centre of note. However, the ordinary Dundonians paid the price for prominence with poor housing and poverty wages. Not surprisingly, such conditions helped create a criminal underclass. Given the hells kitchen in which so many lived, it is more surprising that most people remained honest.