Pagebreaks of the print version

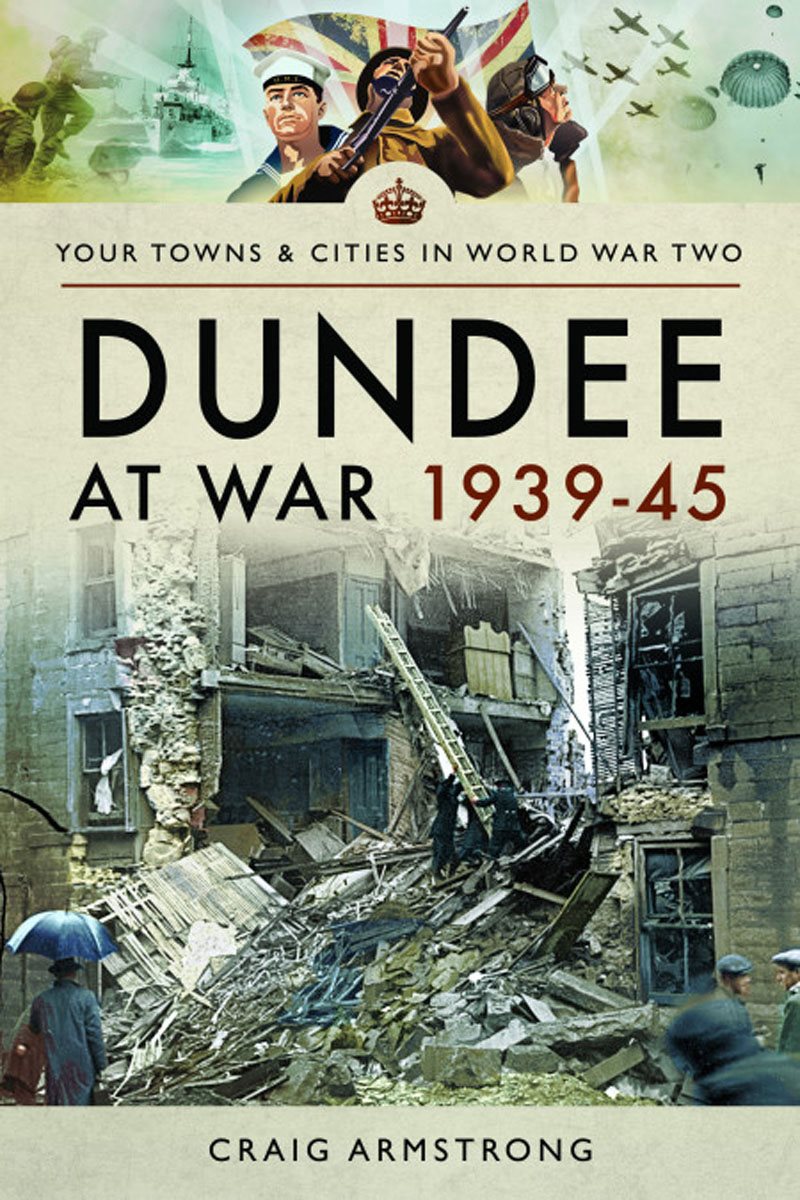

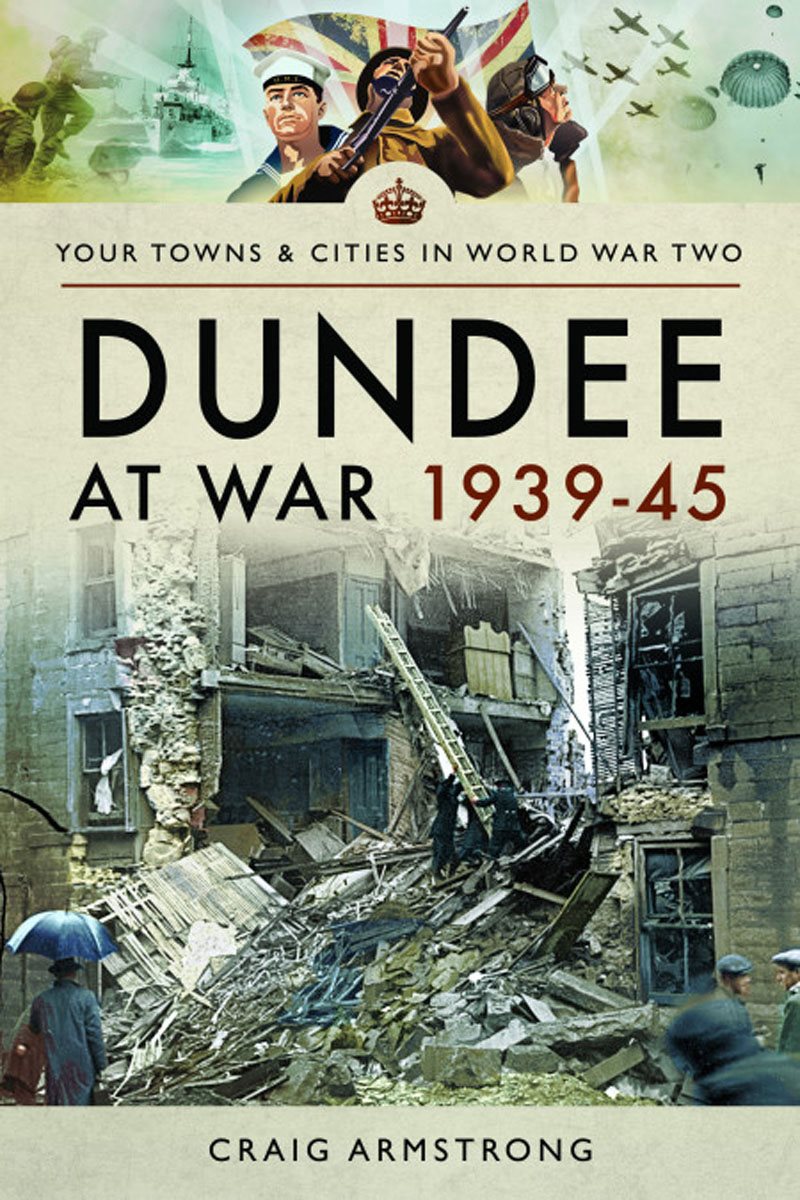

YOUR TOWNS & CITIES IN WORLD WAR TWO

DUNDEE

AT WAR 193945

YOUR TOWNS & CITIES IN WORLD WAR TWO

DUNDEE

AT WAR 193945

CRAIG ARMSTRONG

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Craig Armstrong, 2021

ISBN 978 1 52670 468 9

ePUB ISBN 978 1 52670 470 2

The right of Craig Armstrong to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

CHAPTER 1

1939 Dundee at War

Like many other parts of Scotland, Dundee had suffered during the Depression of the 1920s and 1930s with the jute industry upon which the city depended being particularly hard-hit. Shipbuilding also suffered, along with a number of other minor industries. The inter-war years had been very hard for Dundee with the traditional industries upon which the city depended being badly affected especially jute and shipbuilding. In the worst years of 19311932 over 70 per cent of those previously employed in the jute industry were unemployed. The coming of the war led to a turn-around in both industries; shipbuilding orders took off while the massively increased requirement for sandbags led to a similar recovery in the jute industry.

One of the first jobs at the Caledon Yard was the refitting of two Polish submarines. The Orzel and the Wilk had managed to escape from the Baltic, despite the attempts of the German and Russian forces, and made for Britain. As Dundee was a major submarine base the yard was the obvious location for the repair and refitting operation to be carried out. The Orzel (Eagle) was a modern vessel that had been commissioned in 1939. Damaged by German minesweepers, she had put into the neutral Estonian port of Tallinn. Here, her commanding officer had gone ashore to be treated for an illness and, under German pressure, the Estonians boarded the submarine, interned the crew and set about removing navigational aids and armament.

The crew, however, hatched a daring escape plan and on the night of 18 September they overpowered their guards, cut the mooring lines and set off. The submarine, running half-submerged, was fired upon and ran aground on the bar at the mouth off the harbour. While grounded she was hit and damaged by artillery fire which destroyed her wireless equipment. The crew managed to re-float her though and set course for Britain, after hearing that the Polish submarine Wilk had managed to escape to Britain. The crew put the two captured Estonian guards ashore in Sweden with money and new clothing before setting off across the North Sea. With almost no navigational aids the new commanding officer of the Orzel used a list of lighthouses to find the east coast of Scotland. Lying on the bottom, repairs were made to her wireless and she broadcast a message in English which resulted in a destroyer being sent to escort her.

Attitudes towards the possibility of enemy bombing varied widely in Dundee. There was, of course, the commonly held fear which was shared up and down Britain, but there was also a widespread belief that Dundee would be spared the attentions of the Luftwaffe because the electors of the city had not returned Winston Churchill to office in the 1922 General Election. Churchills bitterness and anger towards the city as a result were well known, as was the fact that he had vowed never to return to Dundee.

One of the first real signs of war coming to Dundee was when the citys evacuation plan was initiated on 1 September. On this first day some 8,800 children and mothers were removed from home to a number of locations in Angus and the Mearns. On this first day children from sixteen schools were evacuated. Evacuees from the more outlying schools were ferried to Union Street by trams and buses and from there they marched in an orderly fashion to the Tay Bridge and East Stations. Mothers carrying young infants were assisted through the queues and helped teachers to care for the children, who all carried their kit in parcels and suitcases along with their gas masks.

The Director of Education, Mr John Cameron, who had the unenviable task of being in charge of the evacuation, told the press that it had gone as smoothly as could be expected and reports from the reception areas showed no problems in finding suitable accommodation. This was largely due to the fact that the numbers that had turned up were far smaller than had been expected and which had turned up during the rehearsals. One woman, however, clearly saw the benefits and jokingly turned up to one of the evacuation centres, telling the officials that she was not part of the evacuation, but asking if she could go with them for the weekend! On the following day a further 13,123 were expected to leave the city.

In the event, fewer children left than expected and by the time the evacuation had been completed on Saturday afternoon, 2 September some 17,200 children and mothers had left the city. Many others, of course, had made private arrangements and the sum of evacuees was in fact higher than the official figure. At Kirriemuir the evacuees from Dundee were welcomed by local Territorials and marched to the hall where a large crowd assembled to greet them and take them to their new homes. Despite the official line that the children were all calm and orderly, the reality was that a great many were anxious and upset over the upheaval which saw them wrenched from their families and familiar surroundings and deposited in an unknown place amongst strangers. Worse still, not every billeting area was pleased to receive them.

Dundee evacuees arrive by bus at East Station . (Dundee Evening Telegraph)

Montrose had seen 2,542 children and mothers sent from Dundee and had managed to billet 1,827 of these. The authorities in Montrose were angered that larger towns, such as Arbroath, had received fewer evacuees from the city, but it would seem that the real reason was rather more sinister. A meeting of the Montrose Town Council held on 11 September saw heated debate, with Councillor Butchart protesting vociferously against the arrangements which had been made. He told the meeting that an excessive number had been sent to the town and that the condition of many of the children, indicated neglect on the part of the responsible authority in the sending area. The councillor concluded by saying that there was no need to go into details about the condition of the children as most of the council had direct experience. The Provost of Montrose contacted the authorities in Dundee to complain about the matter. He noted that this was not a criticism of Dundee, but he had a duty to the people of Montrose who had been badly let down.