Pagebreaks of the print version

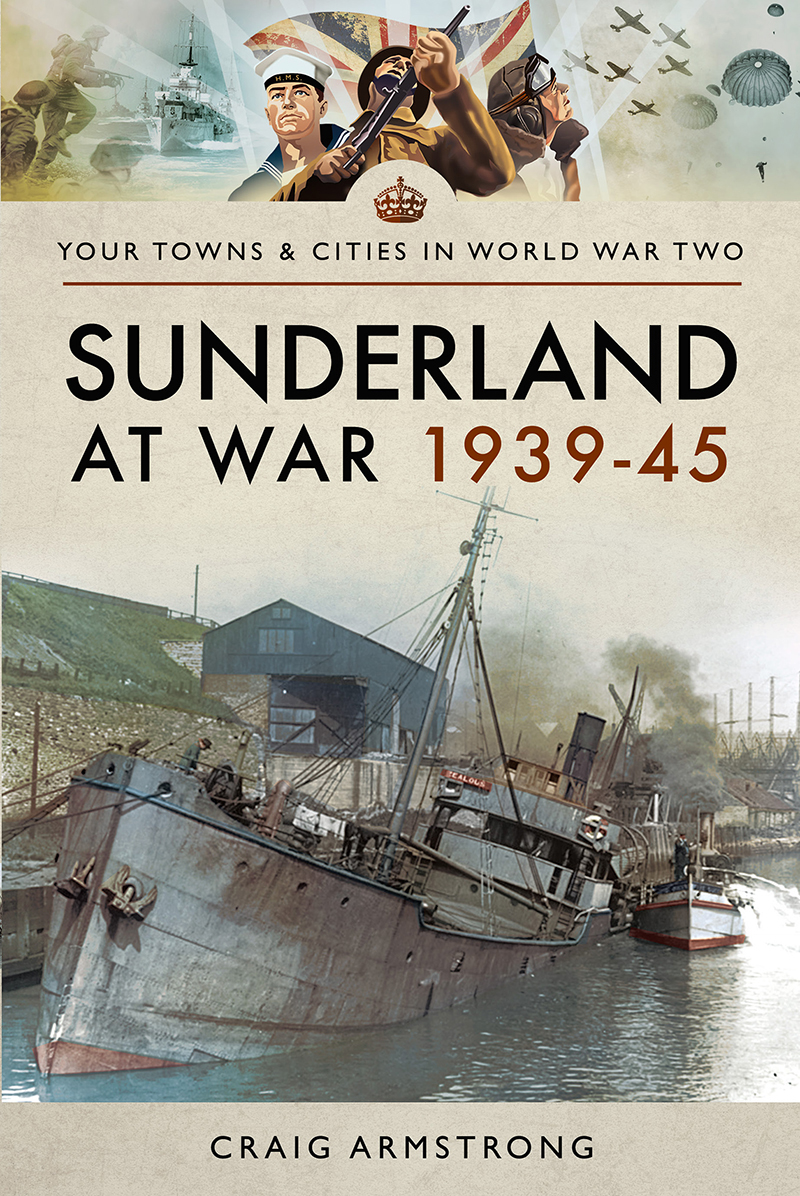

Sunderland at War 193945

Sunderland at War 193945

Craig Armstrong

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Craig Armstrong, 2020

ISBN 978 1 47389 1 258

eISBN 978 1 47389 1 272

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47389 1 265

The right of Craig Armstrong to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

To my Parents

Introduction

Sunderland was an important town with a large number of notable industrial concerns. Mining was one of the key industries and Sunderlands port was vital for a great deal of the export of coal from the Durham coalfield.

The coal industry also led to the development of important glass works in Sunderland. The two most famed manufacturers in the town were Turnbulls Cornhill Flint Glassworks at Southwick and the firm of James A. Jobling & Co Ltd (which had been founded as the Wear Flint Glassworks but was renamed in 1921).

The River Wear, and by extension, Sunderland, had a wellearned reputation for shipbuilding and repairing, especially of merchant vessels. This was to prove vital to the nations war effort and was one of the key reasons for marking the area out as a target of especial interest to the enemy. Firms such as W. Doxford & Sons Ltd., Joseph L. Thompson & Sons Ltd, Sir James Laing & Sons Ltd., Short Brothers Ltd., W. Pickersgill & Sons Ltd., Bartram & Sons Ltd., S.P. Austin & Son Ltd., and John Crown & Sons Ltd. were synonymous with the industry and the area. These were all long-established companies which had made it through the terrible years of the depression in the late 1920s and 1930s. A number of other famous and not so famous yards had failed to weather the storm and had been closed during this awful period, the last being William Gray & Co. Ltd.s Egis Yard, but shipbuilding and repairing remained a key employer in Sunderland at the outbreak of the war.

The firm of Sir James Laing & Sons Ltd. was first established in Sunderland in 1793, but, like most, had struggled during the 1930s. In 1930, the yard had been closed down and the workforce

Short Brothers Ltd. was another famous shipbuilder whose work had stagnated during the 1930s, with the yard being closed on several occasions due to lack of orders. The last of these occasions was in 1938 but the yard was reopened in 1939 and completed two ships that summer: the SS Hermiston and the SS Scorton , both Maierform tramps for Chapmans, a Newcastle company. This highlighted the speciality of the yard, for Shorts was known as the local yard because of the amount of work it undertook for locally based companies.

Like most north-east communities, Sunderland had experienced great hardship during the depression-haunted days of the late 1920s and 1930s, with the shipbuilding industry being particularly hard hit by the slump. Many men lost their jobs, leaving families struggling to survive in straitened circumstances. By the latter half of the 1930s, the industry was beginning to recover although some yards had now gone for good.

Unlike the yards on the Tyne, the shipyards of Sunderland specialised in the building of merchant vessels and many of the yards also specialised in repairing damaged ships. Both of these specialties would prove to be vital to the national war effort and would mark Sunderland out for special attention from the Luftwaffe.

In addition to the shipbuilding there were numerous ancillary industries which supplied material for the shipyards and many Sunderland men worked in these engineering and industrial firms.

CHAPTER 1

1939: The Breaking Storm

With war now declared, the towns ARP personnel were almost constantly on duty in case of the heavy and instant aerial bombardment, anticipated by most. The wardens were not only expected to protect the community against air attack and to enforce ARP regulations such as the blackout, but were also expected to maintain communications and to report any incidents to higher authority. At this early stage of the war, the wardens were woefully under-equipped and methods of communication were haphazard at best. They were often forced to rely on the civilian telephone system, even though there was every chance that the system would be badly disrupted in the event of an air raid. The wardens were at first a sight which provoked curiosity, humour and often ridicule from some sections of the community, especially the younger members of society who had yet to be evacuated.

Sunderland, like most other communities, had a back-up plan for communications during an air raid, which involved ARP messengers, usually young boys from organisations such as the Boy Scouts. This plan was thrown into some confusion just days into the war, however, when insurance problems resulted in the authorities having to order Boy Scouts younger than 14 to cease any work for the ARP services until further notice. Those aged between 14 and 16 could still undertake such duties with their parents permission, but would not be used as messengers during a raid.

A Warden at his Post in a Telephone Box, Observed by a Curious Onlooker (Sunderland Echo)

The evacuation scheme in Sunderland got off to a rather stuttering start and it seemed as though the authorities were rather confused over what official intentions were. Delays had resulted in confusion and muddle over when exactly the evacuation would begin and where the evacuated were to be billeted. This disorganised start was in strong contrast to several other communities. Newcastle upon Tyne had launched its evacuation programme on 1 September (before war was actually declared), Tynemouth and Wallsend began its own evacuations on 4 September, as did many other places such as Edinburgh.

The authorities were increasingly concerned over the numbers of those who had been withdrawn from the evacuation lists in recent days. At one Sunderland school, 70 children had been withdrawn from the scheme out of a total of 240 (29 per cent). Those in charge of the evacuation scheme blamed this mass withdrawal on apathy amongst parents who had been lulled into a false sense of security due to the fact that the massive and immediate bombing which had been expected had not occurred. The Evacuation Officer, Mr W. Thompson, told the local press that this was a foolish attitude as the present, largely peaceful, conditions might not continue and the bombing campaign could begin at any time. He therefore urged all parents to consider the safety of their children and to re-register them. Mr Thompson also informed parents that a large rush of children at the last moment would place too much strain on the transport system and that there would be no further evacuations. This meant that if children were not evacuated in the first round of evacuations they would not have another opportunity.