First published 2000 by Ashgate Publishing

Reissued 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2000 A. J. Arnold

The author has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 00107107

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-72818-9 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-19060-0 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman by Password Publishing Services, Herefordshire, UK

In memory of C. J. Mare (shipbuilder), 1815-98

Chapter One

Introduction

Prior to the First World War, shipbuilding was one of the great capital goods industries and British shipbuilders 'enjoyed a supremacy such as few other industries are ever likely to rival' (Pollard 1952, p. 98; see also Lyon 1980, p. 8). British shipbuilders, 'year upon year launched around 60 per cent of world output' (Slaven 1992, p. 4), helped by the fact that the British merchant marine, representing 40 per cent of the world fleet even in 1914, was largely constructed in British yards. The pre-eminence of British shipbuilding provided strong support for the nation's political power and naval supremacy and the importance of shipbuilding during the nineteenth century was reinforced by the contribution that 'invisible earnings', based upon British domination of world trade, made to the balance of payments (McClelland and Reid 1985, p. 152).

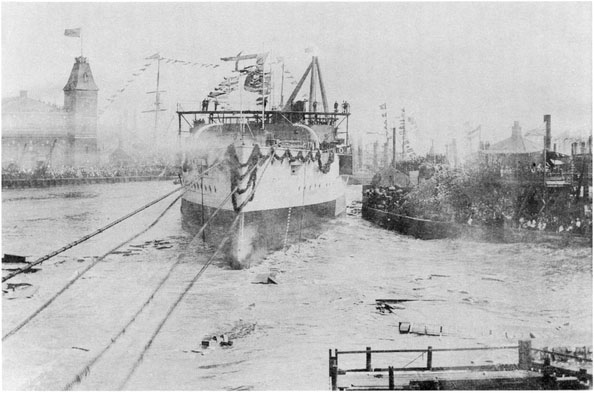

While ships were built from wood, shipbuilding was a highly skilled craft and the Thames was the leading area in Britain, establishing an enviable reputation for the quality of its workmanship, expressed in such phrases as 'river built' and 'Blackwall fashion'. As iron began to replace wood, however, as the main material for the construction of large commercial and naval vessels, the British shipbuilding industry was transformed. Trade boomed and small, skilled craft-based firms were at first overtaken and then eliminated by large, technologically innovative businesses. During the period 1830-75, the shipbuilding trade expanded enormously, employment within the UK trebled, and a trade which was in 1830 still a craft, soon became a branch of the heavy engineering industry (Slaven 1980, p. 107).

Numerous books and articles have been written about the extraordinary growth of the iron shipbuilding trade on the Clyde, Tyne, Tees and Mersey and its impact on those areas, particularly during the latter part of this period but they usually make little reference to the fact that London did not simply decline as the dominant technology changed; instead, with the 'introduction of iron as a shipbuilding material and of steam as the propelling power that supremacy became still more pronounced' (Pollard 1950, p. 72).

Having established itself as the pre-eminent area for the construction of both iron and wooden-hulled ships, shipbuilding on the Thames did then suffer a marked and rapid decline but the reasons for this have never been fully explored; only one article, Pollard (1950), specifically considers the reasons for the decline of shipbuilding on the Thames, although two more recent publications, by Banbury (1971) and Palmer (1993), do provide useful information thereon.

The most obvious factors do not provide a proper explanation for either the growth or the decline of iron shipbuilding; the distance of the London area from the major coal and iron deposits, for example, certainly represented a cost disadvantage which gradually weakened London's competitive position (Pollard 1950, p. 72), yet the region had never been close to the sources of raw materials relevant to ship construction.

The Thames did enjoy some geographically based advantages - its proximity to assured, locally based demand, to sources of capital, to suitable ship construction sites and to skilled labour - but these did not prevent its decline. Some commentators have blamed this on labour problems and costs, as the London shipbuilding unions were unusually well-organised and labour costs were higher than in some other shipbuilding areas. This must have been a contributory factor, as wages make up 30 to 50 per cent of the cost of a ship, but it is all too easy to exaggerate its importance. Pollard concluded instead that 'the Thames managed to hold its own in the first half of the century, when wage differences were just as great, and became increasingly unable to do so after 1850. The main reason for the geographical redistribution must lie elsewhere' (1950, p. 81). Moreover, as Palmer and others have emphasised, 'London's decline was not a consequence of a failure to recognise or act on the opportunities offered by new technology' (Palmer 1993, p. 60; see also Slaven 1980, pp. 110-14).

In the opinion of one historian of shipbuilding on the Clyde, the conditions on the Thames were in fact 'not so dramatically different from the Clyde - wages were higher in the London area, steel had to be transported further and ship repairing had a sapping effect - but none of these alone or collectively explains the demise of Thames shipbuilding during the period of expansion of the industry on Clydeside'. Instead he saw the fact that, within a comparatively short space of time, the country's leading shipbuilding area ceased to build ships at all, as being due to 'mysterious reasons which continue to attract historians and economists to this day' (Walker 1984, p. 43).