Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2013 by Robert McAlister

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

ISBN 978.1.62584.762.1

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.278.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Foreword

As the daughter of the late Harry Hampton, who has often been called the father of conservation in South Carolina, I found Mac McAlisters well-researched history about the forests and waterways of the Lowcountry to be a fascinating education.

While Im quite familiar with the woods and waters near the center of the state, I know nothing about these matters in the Lowcountry. While South Carolinians take pride in being descended from the owners of great rice plantations, Mac points out how much forest was destroyed to clear the way for rice fields. The beautiful woodlands are gone, as are the great rice plantationsanother example of mans shortsightedness in placing too little value on the natural environment.

For many yearsin fact, decadesmy father contacted politicians, nationally known biologists, botanists, arborists and ornithologists in an effort to gain support for his fight to save the last of the old-growth bottomland forests from being cut for timber. He traveled all over the state, speaking to groups he thought might be interested. He even endured booing and insults from people who opposed him.

John Cely, noted conservationist and author of Cowasee Basin, recalls meeting my father when John was an undergraduate at Clemson. My father took him to the Congaree to see some of the champion trees. During their time together, he thought, Heres a man fifty years older than I am who thinks just like me. Apparently, Crazy Old Harry, as some called him, was simply ahead of his time!

This bottomland cypress forest in Congaree National Park shows how Lowcountry swamps looked before logging began. Photo by Mary McAlister.

In the 1970s, when my father was of advanced age and suffering health issues, a group of like-minded young people rallied to the cause. Their activist cry was, Congaree Action Now! Thanks to their youth, passion and energy, they succeeded in winning public and political support. In 1976, Congress declared the area to be Congaree National Monument.

Although my father died four years later, he had lived to see the place he treasured protected forever. He never dreamed that it would later become the Congaree National Park, complete with the Harry Hampton Visitors Center.

Having been lost alone in the Congaree for some twenty-two hours in 2003, I have acquired the nickname Swamp Woman, a moniker Mac McAlister is fond of using.

Harriott Hampton Faucette

Acknowledgements

I have received invaluable help in writing this book from many sources. Mrs. Pat Adams of Bucksville, Maine, furnished genealogical records of the Buck and McGilvery families and historical information about her town. Cipperly Good and the staff of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, provided images and much information about the ship Henrietta. Monica Pattangall, family historian of Lenox, Massachusetts, provided information about the Nickels family and about vessels that traveled to and from Bucksville, South Carolina. The Independent Republic Quarterly reports, published by the Horry County Historical Society, were a valuable resource concerning the Buck family. Thanks to those members and acquaintances of the Buck family who contributed articles to the IRQ, including Charles Joyner, Eugenia Buck Cutts, Constance Fournier, Charles Dusenbury, William H. Pendleton and Sharyn Holliday. Mrs. Henry L. Buck IV of Upper Mill gave me valuable information and allowed access to the original Henry Buck home. Mr. Sidney Thompson was helpful and gave access to Hebron Methodist Church. Mrs. Mary Owens provided much information about the African American community of Bucksport, South Carolina. Julie Warren of the Georgetown County Digital Library provided scans of images of the Atlantic Coast Lumber Corporation and other subjects. Mr. Michael Prevost provided information about forest conservation efforts in South Carolina. Members of the South Carolina Forestry Commission were helpful with historic images and information. Cheryl Oakes of the Forest History Society of Duke University provided a copy of the 1916 article in American Lumberman about the Atlantic Coast Lumber Corporation. Christine Ellis of the Winyah River Foundation provided information about river conservation. Ben Burroughs of the Horry County Archives Center at Coastal Carolina University provided images and information about the Buck family.

Thanks to John Sands, director of the Lowcountry Program for the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, for reviewing the manuscript. I also thank Phillip Wilkinson for his help during our IP canal adventure of 1954. Many thanks to Harriott Hampton Faucette for the foreword and to Cecelia Dailey for reviewing the text and images. Thanks to The History Press for editing the manuscript. My wife, Mary, gave invaluable help by taking photographs and providing ideas and patience during the process.

Introduction

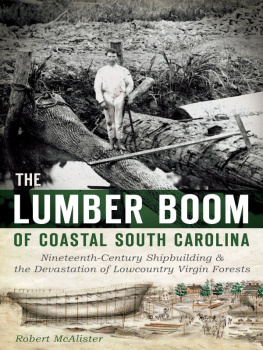

Hundreds of years ago, forests of longleaf pine, bald cypress and oak covered much of the Lowcountry of South Carolina. As far back as colonial times, the tall pines, sturdy live oaks and rot-resistant cypress trees were valued for shipbuilding, both here and in New England and England. After the Buck family relocated from Maine to the banks of the Waccamaw River in the 1820s, the shipbuilders of Maine and the sawmills of South Carolina developed a lasting relationship. The largest wooden sailing ship ever built in South Carolina was built in 1875 in Bucksville, South Carolina, upriver from Georgetown.

It was the lumber barons of the Northeast and Midwest who succeeded in destroying the old-growth forests of South Carolina during the early twentieth century after having been used for generations by smaller industries. A visit to Congaree National Park, which contains the largest stand of bottomland hardwoods in the southeastern United States, will show anyone the various species and sizes of magnificent trees in the Lowcountry before the lumber boom. Located outside of Columbia, South Carolina, the inland Congaree forest is about one hundred miles from coastal Georgetown. It was only after 90 percent of old-growth forests were gone that forestry conservationists began the long, slow process of reforesting.

What follows is the story of Henry Buck and his settlement near Georgetown, the rise and decline of the lumber and shipbuilding industries, the forests in the context of rice production, the modern-day paper industry and conservation efforts in this region. Buck was a venture capitalist, building a business within the laws of his times. His reality was one that included slave labor, and the timber industry was thriving nationwide. With so much of our old-growth forests gone today, it is important to see how they were exploited to understand the value and commodities that a restored forest supplies. Presented here is a greater tale of how an industry can boom and bust, stripping the land of what should be a renewable resource.

Next page