IMAGES

of America

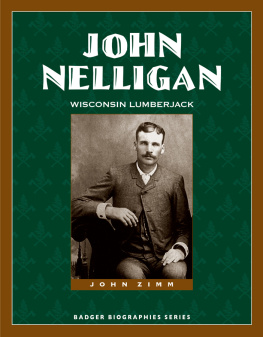

LOGGING IN

WISCONSIN

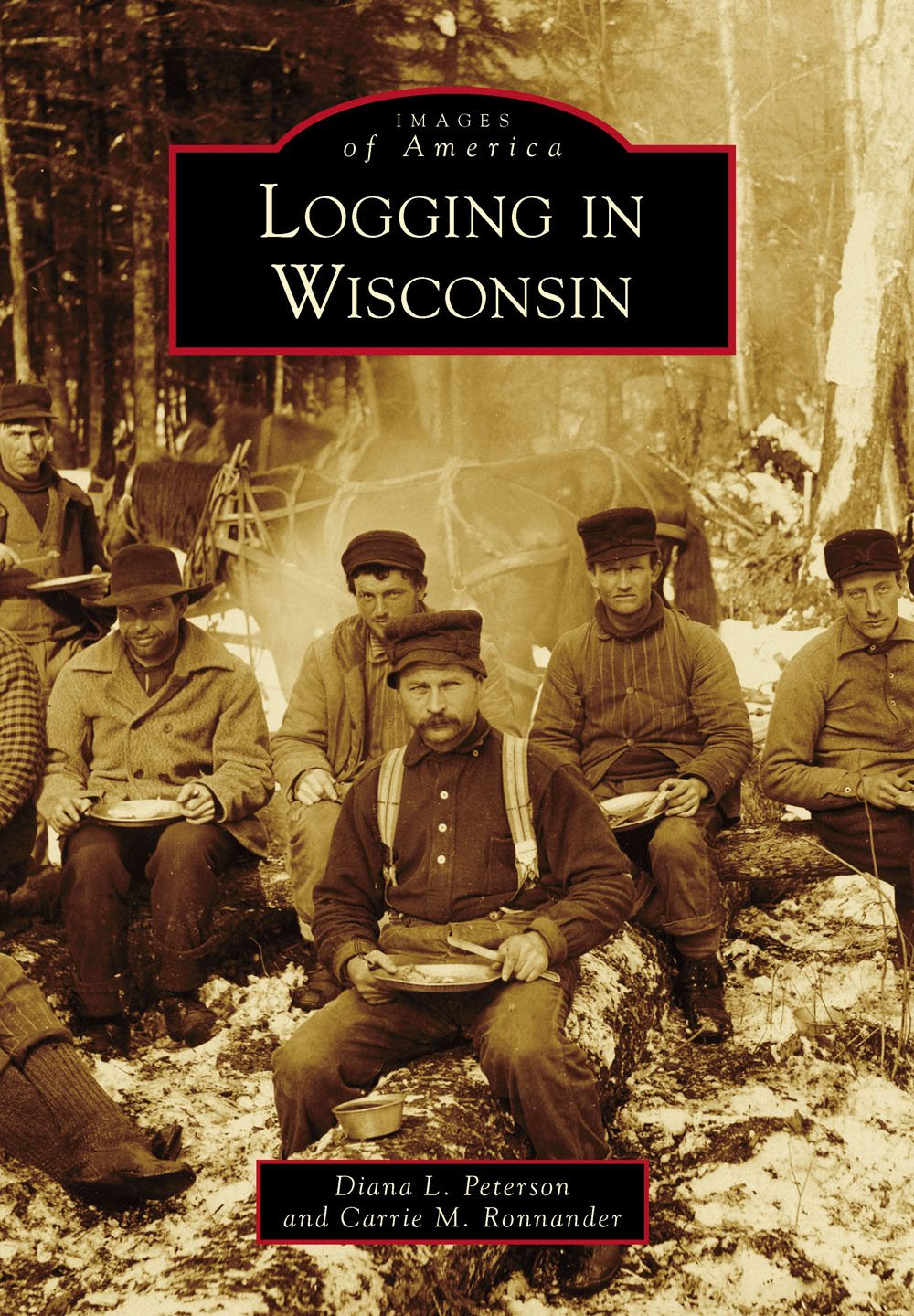

ON THE COVER: A crew eats together in the woods. The cook and cookee would take lunch to the men in a wagon. If the crew did not have to traipse back and forth to the cook shanty, they had more time to work in the woods during daylight hours. (Chippewa Valley Museum.)

IMAGES

of America

LOGGING IN

WISCONSIN

Diana L. Peterson

and Carrie M. Ronnander

Copyright 2017 by Diana L. Peterson and Carrie M. Ronnander

ISBN 978-1-4671-2532-1

Ebook ISBN 9781439661437

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016953351

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe. Abraham Lincoln

We dedicate this book to those historians who spent so much time sharpening the axe. We are especially grateful to Mert Cowley, Dale Peterson, Chad Ronnander, and Malcom Rosholt for their detailed research and illuminating writing about logging history in Wisconsin.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All photographs not otherwise marked are from the Glenn Curtis Smoot Library and Archive at the Chippewa Valley Museum. Former Chippewa Valley Museum librarian Eldbjorg Tobin spent her career making the museums archival and photograph collections more accessible to the public. With quiet perseverance, she catalogued thousands of photographs, including the ones in this book, and helped researchers across the state and nation find images and answers to pressing historical questions. We owe a great debt to Eldbjorg. Without her unsung work, this book would not have been possible.

The Langlade County Historical Society has an amazing collection of photographs, many taken by Arthur Kinsgbury. Joe Hermolin was especially generous with this collection and his time. Andy Barnett at McMillan Library in Wisconsin Rapids, staff at the University of WisconsinLa Crosse Murphy Library Special Collections and the Area Research Center, Karen Furo-Bonnstetter from the Woodville Public Library, and US Forest Service staff at the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest responded quickly to requests to use photographs from their collections. They seemed to understand pressing deadlines. Dunn County Historical Society and Chippewa County Historical Society also provided assistance and access to their photograph collections. Fortunately for us, Gene Kocia retired school administrator, Chippewa Valley Museum volunteer, and eternal student of the logging eradeveloped a presentation on logging just before the first draft of this book was due. We borrowed generously from his research.

For 30 years, the Chippewa Valley Museum and Paul Bunyan Logging Camp Museum have existed side by side, sharing a boundary line in Carson Park, Eau Claire. We are two separate organizations with different missions, but given our physical proximity, we often work together. This book was our greatest joint venture yet. Staff at both museums provided encouragement as we waded through hundreds of photographs and showed great patience when this book pulled us away from administrative work. But perhaps more than anything, the Peterson and Ronnander families deserve special recognition for providing the support to see this project through. They gave up plenty of family time so we could produce this work. Thank you for understanding.

INTRODUCTION

The lumber industry began in the Northeast in America not long after the first Europeans arrived. By the end of the 1700s, shipbuilding increased the need for logging. In 1790, the Northeast exported 36 million board feet of pine lumber and 300 ship masts. By 1830, Bangor, Maine, was the largest lumber ship port in the United States.

After clearing out the land in Maine, the logging industry pushed westward, primarily into Michigan and Wisconsin. While Michigan logging began in the mid-1800s, the majority of the states trees were cut down between 1870 and 1890. In 1862, when the Homestead Act was passed, the logging industry encouraged men to claim their 160-acre plots and sell the logging rights to the well-organized lumber companies.

Shortly after logging began in Wisconsin, it continued on into Minnesota. By the early 1900s, most of the forests were devastated in both of those states and the epicenter of the logging industry moved to the Pacific Northwest. In 1905, Washington became the top lumber producer, and in 1926, it produced an all-time record of 7.6 billion board feet.

The Pacific Northwest has continued its domination of wood production. Global wood consumption is rising, and the Resource Conservation Alliance estimates that the consumption will have a 50 percent rise by 2050.

Logging became a major industry in Wisconsin about 1840 and continued until 1910, peaking in 1890. As lumberjacks moved into the Midwest, the larger camps attracted stores, hotels, saloons, churches, feed mills, and eventually, post offices and railroad stations, which led to the creation or expansion of cities including Eau Claire, Oshkosh, Stevens Point, and Wausau.

Wisconsin became a significant player in lumber production. Incorporated in 1844 in Menomonie, the Knapp-Stout & Co. Company became the largest lumber company in the world. Eau Claire had more sawmills than any other city in the world, and Chippewa Falls had the largest indoor sawmill in the world.

The logging industry physically changed the state of Wisconsin. Thousands of acres of trees were cut down, leaving northern Wisconsin strewn with stump-filled lands. Dams and holding ponds were built that redirected the waters of Wisconsin rivers. Villages sprang up to house and support workers.

The logging industry changed the people of Wisconsin. Hardworking men came to Wisconsin from the woods of Maine and Michigan or from a variety of European countries to become lumberjacks. Many of these men settled in Wisconsin and raised families here.

The logging profession changed the economy of Wisconsin. Logging overtook agriculture for a few decades as the dominant financial system in Wisconsin. When the lumber era was over, new uses for the land had to be found. While some dedicated farm families tackled the cutover land, much of it was replaced with trees in the 1930s and 1940s, promoting the growth of papermaking and creating a tourism industry. Both industries remain an important part of Wisconsins economy today.

In 1852, Wisconsin representative Ben Eastman reassured Congress that the forest had enough lumber to supply America for all time to come. Two years later, the Wisconsin Pinery journal in Stevens Point reported that 50 years of logging would scarcely make an impression on these boundless forests. Sadly, these statements were gross underestimations. In 1840, the census included 124 sawmills, and by 1865, there were 620 sawmills. At that time, the lumber produced was valued at $4.3 million, and by 1890, the value had increased to $60 million. By 1910, the forests were totally ravaged, and it was not until after World War II that they were restored.

Mark Wyman, author of The Wisconsin Frontier, sums up the devastation: Great stumps like bleached skeletons littered the landscape, which supported no trees beyond a few inches in diameter. With much of the forest destroyed and ground cover burned, floods became frequent and large and sudden flows caused year-round river levels to fall sharply. Pine seed supplies declined and white pine blister rust attacked younger trees opening the way for species like aspen. Ecologically, no force since the glaciers has rivaled northern logging in either its immediate or long-term effects.

Next page