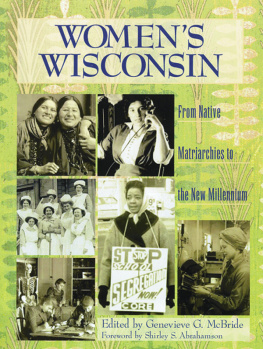

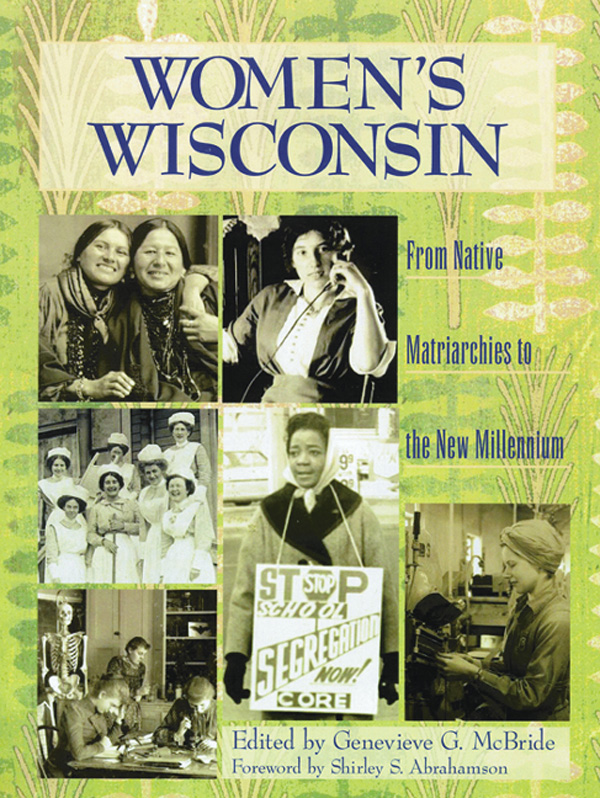

WOMENS

WISCONSIN

From Native Matriarchies to the New Millennium

Edited by Genevieve G. McBride

Published by the

Wisconsin Historical Society Press

2005 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

E-book edition 2014

For permission to reuse material from Womens Wisconsin (ISBN 978-0-87020-361-9, e-book ISBN: 978-0-87020-563-7), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

www.wisconsinhistory.org/publications

Photographs identified with PH, WHi, or WHS are from the Societys collections; address inquiries about such photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the above address.

Designed by Jane Tenenbaum

09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Womens Wisconsin : from native matriarchies to the new millennium / edited by Genevieve G. McBride.

v. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Contents: The first Wisconsin womenWomen on the Wisconsin frontier, 18361848Statehood and the status of women, 18481868Poverty and progress for women in Wisconsin, 18681888Organized women, 18881910Forward women in Wisconsin, 19101930 Women at war, 19301950.

ISBN 0-87020-361-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. WomenWisconsinHistory. I. McBride, Genevieve G.

HQ1438.W5W64 2005

305.409775dc22

2005001067

Photographs: FRONT COVER, top to bottom, left to right: Ho-Chunk women pose for a portrait, Black River Falls, ca. 1915. WHi Image ID 10151; switchboard operator at her post, Washington Island, ca. 1915. WHi Image ID 9212; nurses pose in uniform, Milwaukee, ca. 1900. WHi Image ID 6942; CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) picket protests school segregation, Milwaukee, 1964. WHi Image ID 4993; students at Milwaukee-Downer College conduct scientific research, Milwaukee, 1900; woman working at the Badger Ordnance Works, Baraboo, ca. 1943, WHi(V51)58.

Dedicated in gratitude for their years of service in the first century of the Wisconsin Historical Society to Isabel Durrie (18701889), Annie Nunns (18891942), and Minnie M. Oakley (18891910); and for their works within this work to Louise Phelps Kellogg (19011942), Lillian Krueger (19291956), and Alice E. Smith (19291965); and to all of the women workers of the Wisconsin Historical Society, past and present, who preserved the past of all Wisconsin women and made this work possible.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

I am a Wisconsin woman, albeit one who was born in New York City. In the year of my birth, 1933, our nation was in the midst of the Great Depression, Franklin Delano Roosevelt had just been elected president in one of the early elections in which women had the right to vote, and Germany was on the verge of naming Adolf Hitler its chancellor. The world was lurching toward the Second World War and I, as a young girl, had the good fortune to be sheltered from the weightier problems facing our nation and the world. I spent my early years practicing English (Yiddish, the native tongue of my parents, who were immigrants from Poland, was my first language) and my teen years occupying myself with the myriad fascinations of New York City and a small neighborhood grocery store that hummed with life across the street from my familys apartment. The store Leos belonged to my parents, Leo and Celia Schlanger. Its shelves were packed with a jumble of dry goods and the air was rich with the aroma of the meats and cheeses that were stocked in the deli case.

Our lives revolved around that tiny precious square of real estate on Manhattans Upper West Side. It was where work, neighborhood, and family converged; it was our community. And, like most places that settle in our hearts, it was special not for its towering stacks of cans or its gritty tile or high glass counter, but for the people it brought together. How I delighted in the diverse group that stepped across the threshold of our little store each day: the friends and neighbors and strangers, young and old, worried and carefree. Some rushed, some browsed, some argued, some stayed sufficiently long to outline what was wrong with the world, and others stayed a bit longer and solved a few of those problems. It was untidy, unpredictable, and I loved it. And somehow I knew, from about the age of 6, that if I became a lawyer I could work with people just as interesting as my parents customers, and I wouldnt have to stock shelves.

My work as a lawyer and a judge has indeed allowed me to find a spot at the center of a similarly lively jumble of humanity. There is nothing like the bustle and hum of business under the dome of our State Capitol and in the corridors of our many magnificent county courthouses. And as was true at Leos, it is not the buildings but the people within them who make the court system a very special place to work. Our diverse backgrounds and perspectives increase the quality of our decisions and improve the chance of success of every initiative we undertake. So I am grateful that there has been a place for me, mindful of the sacrifices of the women and men who broke down some of the barriers along the path that I have navigated, and honored to have played a role in eliminating barriers for others.

That the child of an immigrant grocer and a girl, no less could become a lawyer was, I am sure, unthinkable to many of the people who crossed my parents threshold. And indeed I might not have become a lawyer but for the fact that my father had a heart attack when he was in his early forties. He survived, but the event underscored for my parents the reality that my mother might someday have to support my sister and me on her own. They became convinced that their girls must be raised to be self-sufficient.

My parents encouraged me to get a good education, and I took their advice. I was one of a handful of women at Indiana University Law School and the only one in the graduating class of 1956. Around the nation at that time law schools were beginning to open their doors to women, and it was a very difficult change for some within the system. At Harvard Law School, which began admitting women in 1950, some professors controlled the participation of their female students by instituting Ladies Day generally, a single class each month when women students were invited to speak. And, of course, designating restrooms for women and dorms for women required substantial study and careful consideration.

I graduated high up in my class, an achievement that normally guarantees offers of employment from at least a few law firms. But the only offers that the dean of the law school thought would come my way were offers for librarian positions which are great jobs for someone who is trained and interested in that field. When I did find a law firm willing to take on a woman in Madison, Wisconsin I seized the offer and stayed fourteen years. While in private practice I became a professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School, and later I left practice to become a Supreme Court justice.

If law is truly going to serve the publics interest, the profession must be opened wide to all people who wish to serve. I am happy to say that, in 2005, about half of all law school graduates are women, three of our seven Supreme Court justices are women (and we welcomed our first African American justice), and the State Bar of Wisconsin has had women presidents (one of whom also happened to be African American). But work remains to be done. There is equal access to the profession but not yet equal representation in the management of law firms and at the high end of the salary scale.