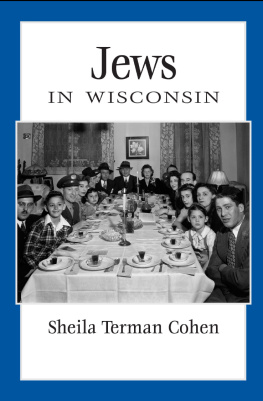

JEWS

IN WISCONSIN

Sheila Terman Cohen

Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past

by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories. Founded in 1846,

the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions.

wisconsinhistory.org

Order books by phone toll free: (888) 999-1669

Order books online: shop.wisconsinhistory.org

Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership

2016 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

E-book edition 2016

For permission to reuse material from Jews in Wisconsin (ISBN 978-0-87020-744-0; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-745-7), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

Publication of this book was made possible in part by a generous gift from the Marcus Corporation.

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Excerpts from Louis Hellers journals are reprinted with permission from the Milwaukee Jewish Museum archives.

Designed by Jane Tenenbaum

20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cohen, Sheila, 1939-, author.

Jews in Wisconsin / Sheila Terman Cohen. First edition.

1 online resource.

ISBN 978-0-87020-745-7 (Ebook) -- ISBN 978-0-87020-744-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. JewsWisconsinHistory. I. Title.

F581.C64 2015

977.5004924--dc23

2015035736

To my husband, Marc, son of a Jewish Russian immigrant, born and raised in Appleton, Wisconsin. This is, in part, his story.

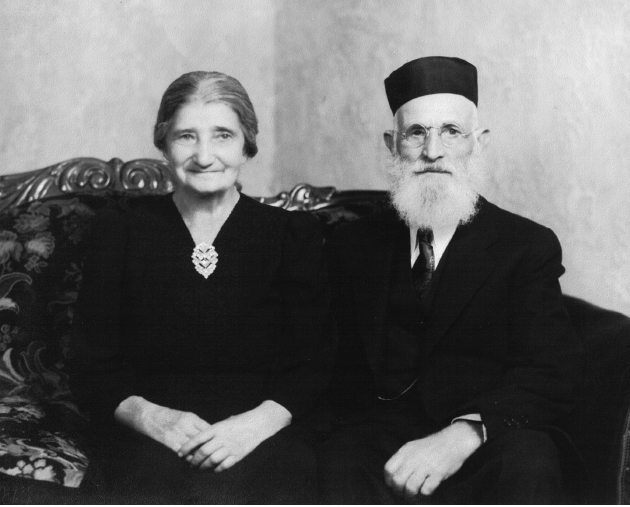

Nissan and Chai Sarah Alperovitz were among the early Jewish settlers who emigrated from Belarus to Sheboygan in the late 1800s to early 1900s. The Alperovitzes, pictured here in their Americanized clothing in 1937, arrived in 1906 along with other members of their family. Nissan became a cattle dealer and often served as cantor at the neighborhood synagogue, Ahavas Sholem Shul.

Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses

yearning to breathe free,

the wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Emma Lazarus, Jewish poet

The famous lines of The New Colossus, written by the Jewish poet Emma Lazarus in 1883 and engraved onto a bronze plaque at the base of the Statue of Liberty ten years later, symbolize Americas historic openness to immigrants from all over the world. They could not have been more meaningful than they were to Jewish refugees who left their tempestuous pasts behind to find a safe haven in the United States.

Unlike other peoples who have come to the United States in search of a better life, the Jews who made that journey are united not by a single country of origin but by a shared history, one that spans four thousand years of varied experiences and locales. Over that long history, the word Jewish has at times been used to refer to a religion, a nationality, an ethnicity, and a culture. In a sense, all of these terms can be applied, depending on ones perspective.

Although there is no one credo that people must follow to call themselves Jewish, Judaism as a religion is guided by the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. In its text, the Torah prescribes the basic tenets of the Jewish faith, which at its core rests on the belief in one God only. Extended from that concept are centuries of rabbinic interpretations that teach the principle that each individual is created in Gods image and must therefore be treated with respect and justice. Such core ideas are underscored in the Hebrew words tzedakah, the importance of giving; tshuvah, the need to repent for ones wrongdoings; and tefillah, the need to pray and give thanks for ones blessings. The Ten Commandments found within the Torah reflect such ideals of honoring God and all of humanity.

Within the basic structure of the Jewish faith are three major divisions: Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform. Each reflects a different level of strict observance of Jewish religious practices, with Orthodox being the most observant, Conservative less so, and Reform the most liberal iteration of the same basic ideas. In more recent times, other groups have formed, including Reconstructionist and Humanist branches, which present their own nuanced beliefs and degree of observance. The Reconstructionist movement embraces a belief that God is present in all of nature and is not a single anthropomorphic entity, while the Humanist group focuses on the human capacity to create a better world without theistic underpinnings.

Although some people born into a Jewish home do not practice any form of the religion, their values often reflect the Jewish teachings of creating a just and equitable society. The Jewish tenet tikkun olam, translated from Hebrew as repair of the world, is a call to Jews to do justice and pursue righteousness for all of humanity. Many Jews, whether religious or not, tend to manifest such concepts in their political and social values that aspire to create social justice for all.

However, Jews have frequently not been the beneficiary of the just and equitable society they espouse. Since their earliest origins in Mesopotamia nearly four thousand years ago, Jews have suffered periods of persecution that have driven them to find safe refuge elsewhere in the world. Throughout their earliest history, this monotheistic people found themselves at the mercy of Assyrian, Babylonian, Egyptian, and Roman rulers who persecuted them. As early as 1000 CE, large numbers of Jews fled these rulers and settled into what became the Germanic Confederation and Russian-dominated areas of Europe. Another stream of Jewish immigrants had put down roots in the areas that are now Spain, Portugal, Italy, Turkey, and North Africa. These diverse migrations to separate areas of the globe resulted in the formation of two distinct subcultures of Judaism referred to as Ashkenazim (German) and Sephardim (Spanish). Each group developed different religious traditions, dietary practices, and languages reflective of the area they occupied.

Throughout the ages, virulent myths about Judaism led to persecution of its followers. False tales of evil religious practices prevailed. The belief that Jews used the blood of Christian children in their rituals was passed down through generations. Jews were stigmatized as Christ killers by those who believed that non-Christians were inferior infidels. Such beliefs led to violent attacks on Jewish communities and repeated attempts to force Jews to convert to Christianity. Resistance to forced conversion between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries gave way to the Roman Catholic Churchs Crusades, a series of Holy Wars against non-Christians that brought about the wholesale slaughter of Muslims and Jews alike. In the late Middle Ages, a Roman Catholic tribunal conducted the Spanish Inquisition, forcing Jewish heretics (nonbelievers) to convert to Catholicism or be put to death. The interrogations led to the expulsion of all Jews from Spain in 1492. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, thousands of Jews living in czarist Russia were killed in three waves of pogroms (massacres). The most blatant and recent attempt to annihilate the Jewish people was the German Holocaust of World War II, during which six million Jews perished.

Next page