Make Way for Liberty

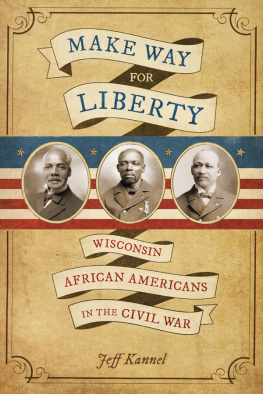

Make Way for Liberty Wisconsin African Americansin the Civil War

Jeff Kannel WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press Publishers since 1855 The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories. Founded in 1846, the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions. Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership 2020 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin E-book edition 2020 For permission to reuse material from

Make Way for Liberty (ISBN 978-0-87020-946-8; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-947-5), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users. Photographs identified with WHI or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

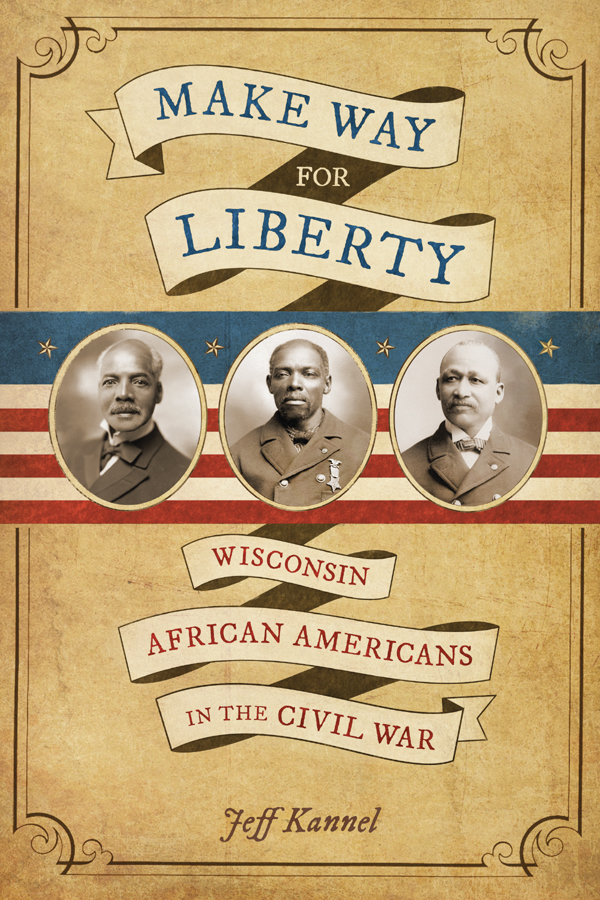

Front cover images, from left to right: Benjamin Benny Butts (Fifth Wisconsin Infantry), UW Archives; Horace Artis, ca. 1900 (Thirty-First USCT), Wisconsin Veterans Museum; and Joseph M. Ellmore, ca. 1900 (USCI), Wisconsin Veterans Museum Designed by Sara DeHaan 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kannel, Jeff, author. Title: Make Way for Liberty : Wisconsin African Americans in the Civil War/ Jeff Kannel. Other titles: Wisconsin African Americans in the Civil War Description: [Madison] : Wisconsin Historical Society Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020007880 (print) | LCCN 2020007881 (ebook) | ISBN 9780870209468 (paperback) | ISBN 9780870209475 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Participation, African American. | WisconsinHistoryCivil War, 18611865Participation, African American. | African American soldiersWisconsinHistory19th century. | African AmericansWisconsinHistory19th century. | African AmericansWisconsinBiography. Classification: LCC E540.N3 K275 2020 (print) | LCC E540.N3 (ebook) | DDC 973.7/475092396073dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007880 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007881 Publication of this book was made possible in part by a grant from the Amy Louise Hunter fellowship fund and by support from the Wisconsin Historical Society Press Readers Circle.

For more information or to join the Readers Circle, visit support.wisconsinhistory.org/readerscircle. This book is dedicated to the African American soldiers and sailors who served from Wisconsin in the US Civil War, as well as their descendants. May their sacrifices, service, and contributions to the state and nation be respected and remembered. Contents The creation of this book began around 2009 at an event I attended at the Civil War Museum in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Present at the event was a group of African American Civil War reenactors portraying Company F, Twenty-Ninth United States Colored Infantry (USCI). They introduced me for the first time to the Milwaukee Company: black soldiers from Wisconsin who fought in the Battle of the Crater during the Siege of Peters-burg. I admitted with embarrassment that I knew nothing about black Civil War soldiers from Wisconsin.

After all, my father, Wayne, was a retired high school history teacher with special interest in the Civil War. When I told him about meeting the reenactors, he said that he too was unaware that there had been African American soldiers from Wisconsin in the war. He may have been more surprised and embarrassed than I. I decided on that day to learn what I could about this history and why it wasnt better known. During the past ten years, I have found that the story of these real-life soldiers and freedom fighters should occupy a prominent place in Wisconsins Civil War history. Although the number of Wisconsin African Americans who served is quite small compared with the number of white soldiers, black men served in disproportionately high numbers relative to their population in the state.

The core issue of the Civil War was slavery, and the presence of black men and women in the state and their part in the war effort brought the issue home, even to people who initially chose to believe that the war could be ended without addressing slavery. Some of these individual stories are stories of achievement. These contrast with the lives of the majority of their comrades, who were less successful in overcoming racism, discrimination, poverty, disability, a lack of education, and a lack of opportunity. Together, the stories in this book reveal the complicated and often contradictory response of many white Americans to the African American men who helped save the Union: some black veterans were accepted and respected for their service, while others were rejected and sometimes assaulted because of their race. The title of this book is taken from a hopeful and positive editorial that appeared in the New York Anglo African weekly newspaper in the first month of the war. In sections addressed to white Unionists, it said, If you would restore the Union and maintain the government you so fondly cherish, make way for liberty, universal and complete.

But the day of supplication is pastthe hour of action is at hand. The black man, either with cooperation or without it, must be ready to strike for liberty whenever the auspicious moment comes. To black readers, it said, Let us concentrate our energies and unite our hearts, by taking counsel with each other how slavery can most speedily be abolished. In Race and Reunion, historian David W. Blight documents the systematic effort by southerners and many northerners to deny that slavery was the principal cause of the Civil War. Southern whites, including most Confederate veterans, began as soon as the war ended to create and promote the mythology of the Lost Cause: that secession was a noble crusade for liberty that failed only because of the Norths superior numbers and economic power.

In the Lost Cause myth, the defeat of Reconstruction and triumph of white supremacy were portrayed as victories benefiting the whole nation. Sectional reconciliation was promoted by white Union and Confederate veterans, who together celebrated their previous suffering and valor while avoiding discussions of race. For African Americans, there would be no return to enslavement. However, the seemingly bright future when the war ended, and the progress made during Reconstruction, were wiped out by a combination of racist violence, legal backtracking, and eventual abandonment by the Republican Party. Black veterans watched from the sidelines as their role in winning the war and eliminating slavery was forgotten by the surrounding white society. For white veterans North and South to clasp hands across the bloody chasm, black veterans had to be excluded.

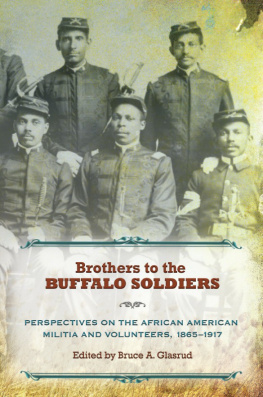

With few exceptions, writers of history and fiction followed this same path, glorifying the bravery and sacrifice of white soldiers on both sides and ignoring or glossing over issues of race and slavery. Even at the local level, African American participation in the war was erased. In the Civil War chapter in a 1912 history of Fond du Lac County, the author listed every white man who served from the county but included none of the black In the late nineteenth century, a few African American veterans did write about the role that black soldiers played in the Civil War. George Washington Williams, a veteran of the USCT and the Buffalo Soldiers, and later a minister, Ohio legislator, and historian, wrote

Make Way for Liberty Wisconsin African Americansin the Civil War

Make Way for Liberty Wisconsin African Americansin the Civil War