Minority Soldiers Fighting in the Civil War

JOEL NEWSOME

Published in 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CS17CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Newsome, Joel.

Title: Minority soldiers fighting in the Civil War / Joel Newsome.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square, 2018. | Series: Fighting for their country: minorities at war | Includes index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781502626622 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502626561 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Juvenile literature. | United States. Army--African American troops--History--19th century--Juvenile literature. | United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--African Americans--Juvenile literature. | United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Participation, African American--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E468.N49 2018 | DDC 973.7--dc23

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Caitlyn Miller

Copy Editor: Alex Tessman

Associate Art Director: Amy Greenan

Designer: Stephanie Flecha

Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of:

Cover Photo Researchers/Getty Images; Archive Photos/Getty Images.

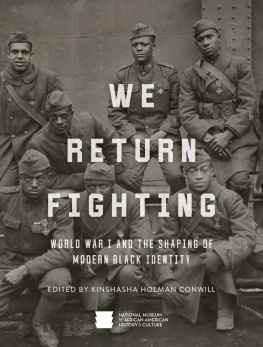

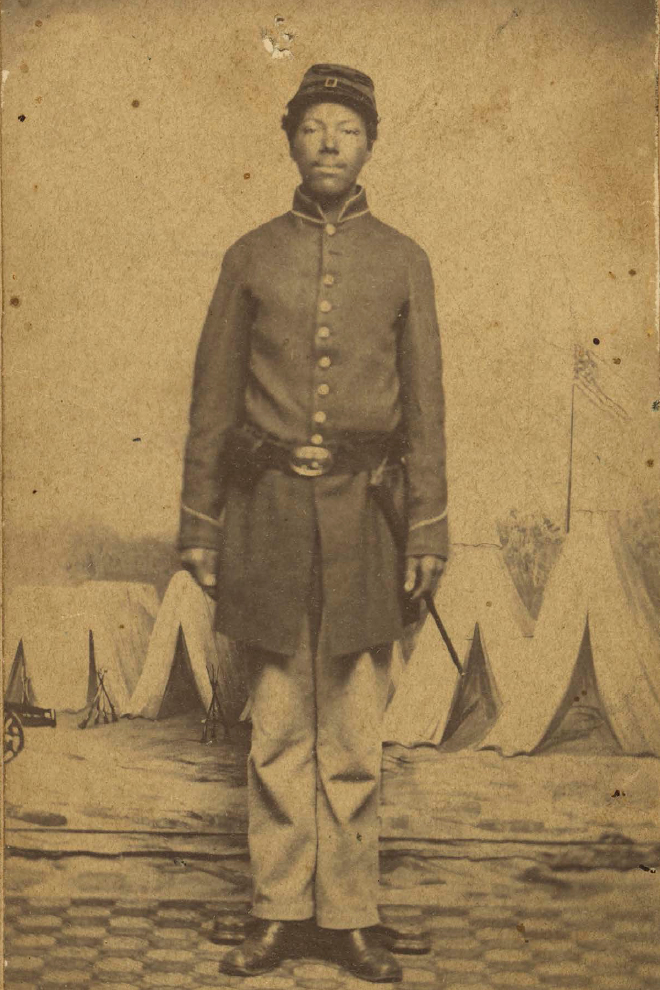

John S. Parker, pictured here, was one of thousands of African Americans who rushed to enlist in the armed forces.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

A Nation Divided

T hroughout history, many societies have depended upon marginalized minority citizens to defend their nations in times of conflict. Yet the American Civil War is unique. Slavery, the conflict that sparked the war, was central to the lives of the largest minority population in the young United States: African Americans. Though there were free black communities in the United States, the vast majority of black Americans were enslaved at the time of the war. As abolitionist movements grew and the country expanded westward, the future of the so-called peculiar institution inspired vehement debate. Slaveholders advocated for legal slavery in new territories and harsher penalties for runaway slaves and their supporters, while abolitionists envisioned the end of human bondage in the United States.

In 1619, the first kidnapped Africans were delivered to the colony of Jamestown, Virginia. African slaves were trafficked to help grow crops, such as tobacco and rice. As the slave trade grew, the institution of slavery spread throughout the early American colonies. More than one hundred and fifty years before the Declaration of Independence was signed, slavery was already a cornerstone of the fledgling American economy. The slave trade was a massive international operation that immediately flourished: historians have estimated that between six and seven million Africans were kidnapped and transported to the United States in the eighteenth century.

After the American Revolution, many Northern cities began to distance themselves from the institution of slavery, and the abolitionist movement started as its first proponents called for an end to legal human bondage. Yet Northerners still enjoyed the fruits of slave labor, getting rich on Southern investments or simply being able to afford cheap goods priced as the result of free labor, though the institution of slavery was not as widespread in the North as it was in the Southern states whose economy depended upon agriculture.

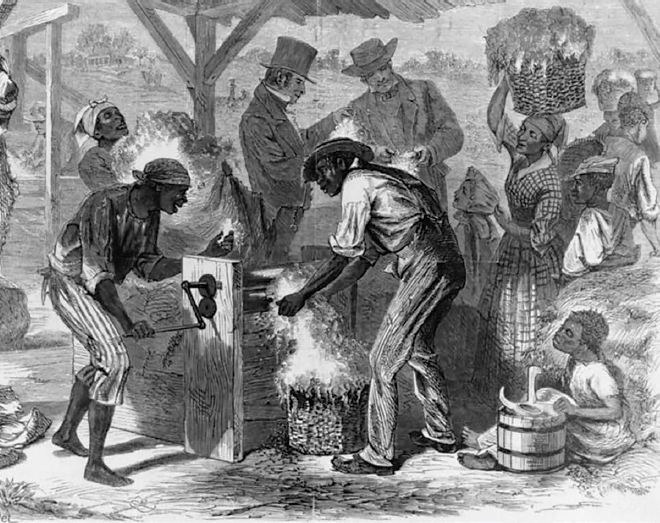

By the late 1700s, the price of tobacco fell, and Southerners felt the squeeze of a dragging economy. In 1792, a recent graduate of Yale University, Eli Whitney, moved from New England to a Georgia plantation to work as a private tutor. Whitney soon discovered that Southern farmers were in desperate need of a way to make cotton a profitable crop. The problem was that the vast majority of cotton grew with sticky seeds that had to be removed from the fluffy boll. Removing the seeds was time consuming and limited the amount of cotton that could be effectively harvested. Whitney invented a machine that removed the seeds from unprocessed cotton in a fraction of the time it took to do so by hand.

Whitneys invention of the cotton gin invigorated the Southern economy and increased the Southern demand for slave labor exponentially. While the cotton gin did the work of separating the seeds from the boll, enslaved people still grew and harvested the crop. The young American economy flourished along with slavery. Cotton was grown in the South but shipped to the North to be processed and woven into clothing and other goods. Between 1790 and 1860, the number of slave states increased from six to fifteen. Congress banned the international slave trade in 1808, but over the next fifty years, the enslaved population almost tripled. While the international slave trade was prohibited, the domestic slave trade was alive and well. By 1860, there were more than four million enslaved people living in the United States. The majority were located in Southern states and accounted for a third of the Souths total population.

While slavery expanded in the South with the arrival of Whitneys cotton gin, the question of westward expansion loomed over the land. Bloody conflicts between civilians raged in new territories while the United States government struggled to produce a solution that would appease slaveholders and end the violence among white citizens. Though history remembers the Civil War as the conflict that freed the slaves, the majority of white Americans who lived through it did not agree that the war was fought over human bondage. Many white people viewed the war as a conflict about states rights and resented the idea that African Americans should be liberated. As the bloodiest war in American history raged, the question of whether or not to free and arm African Americans was met with suspicion and derision by many white people in both the Union and the Confederacy.

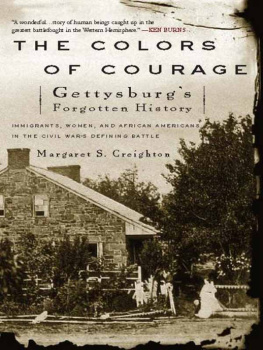

The cotton gin led to the expansion of slavery.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION