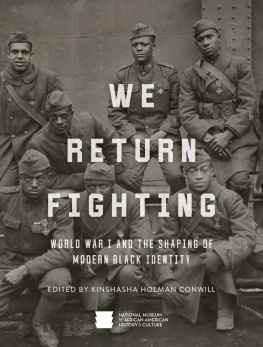

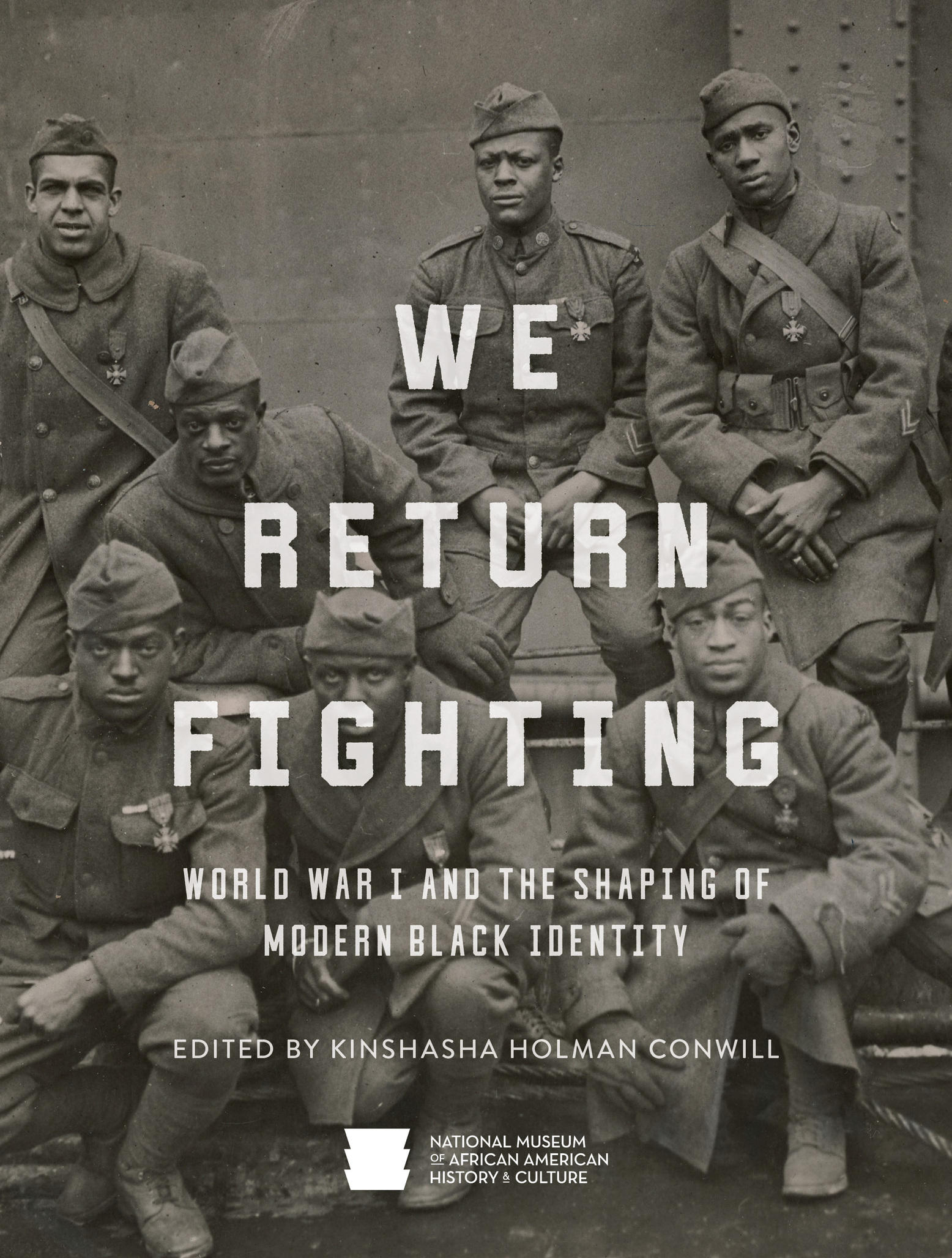

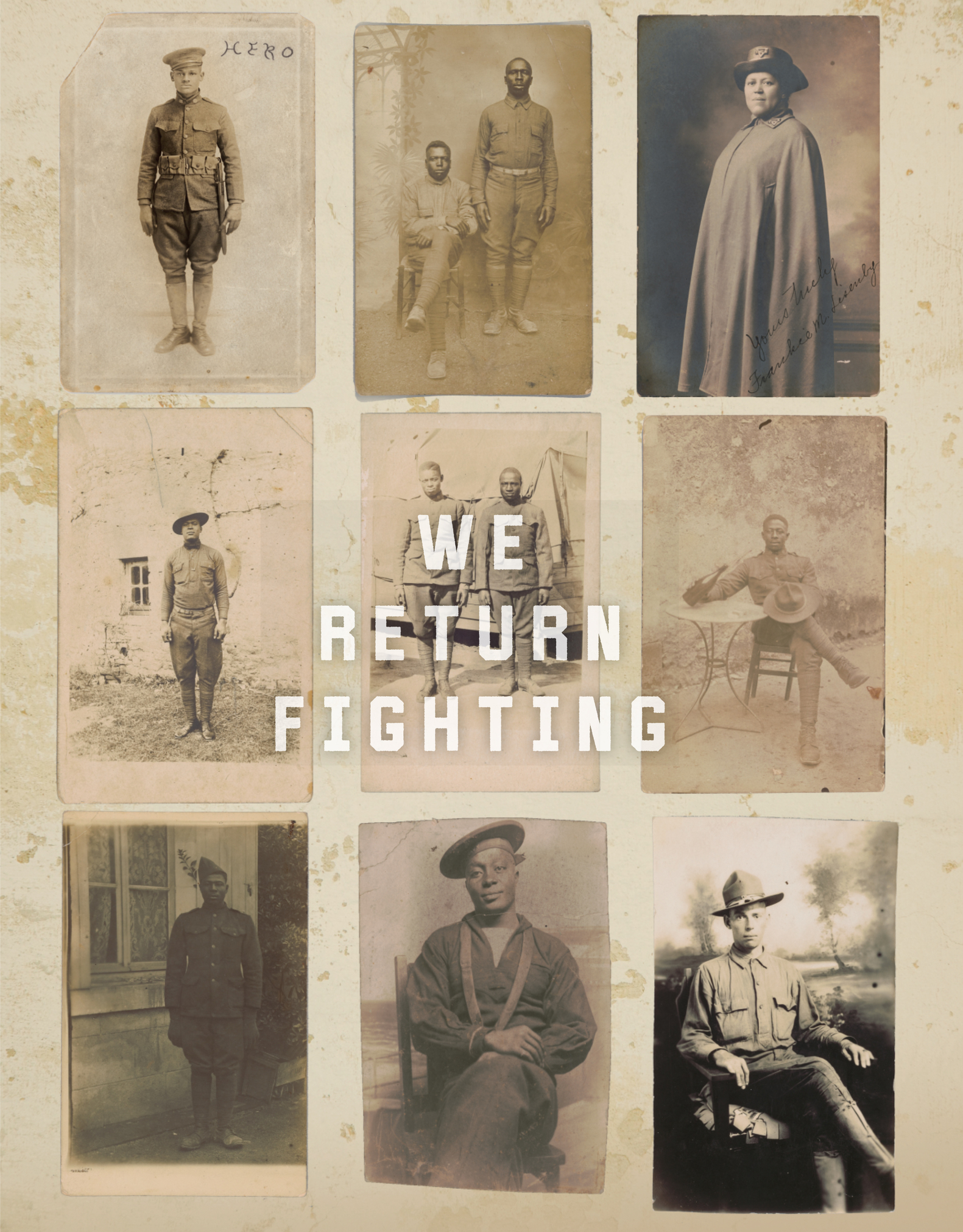

Photographs of African American soldiers, sailors, and nurses during World War I, 1916-19.

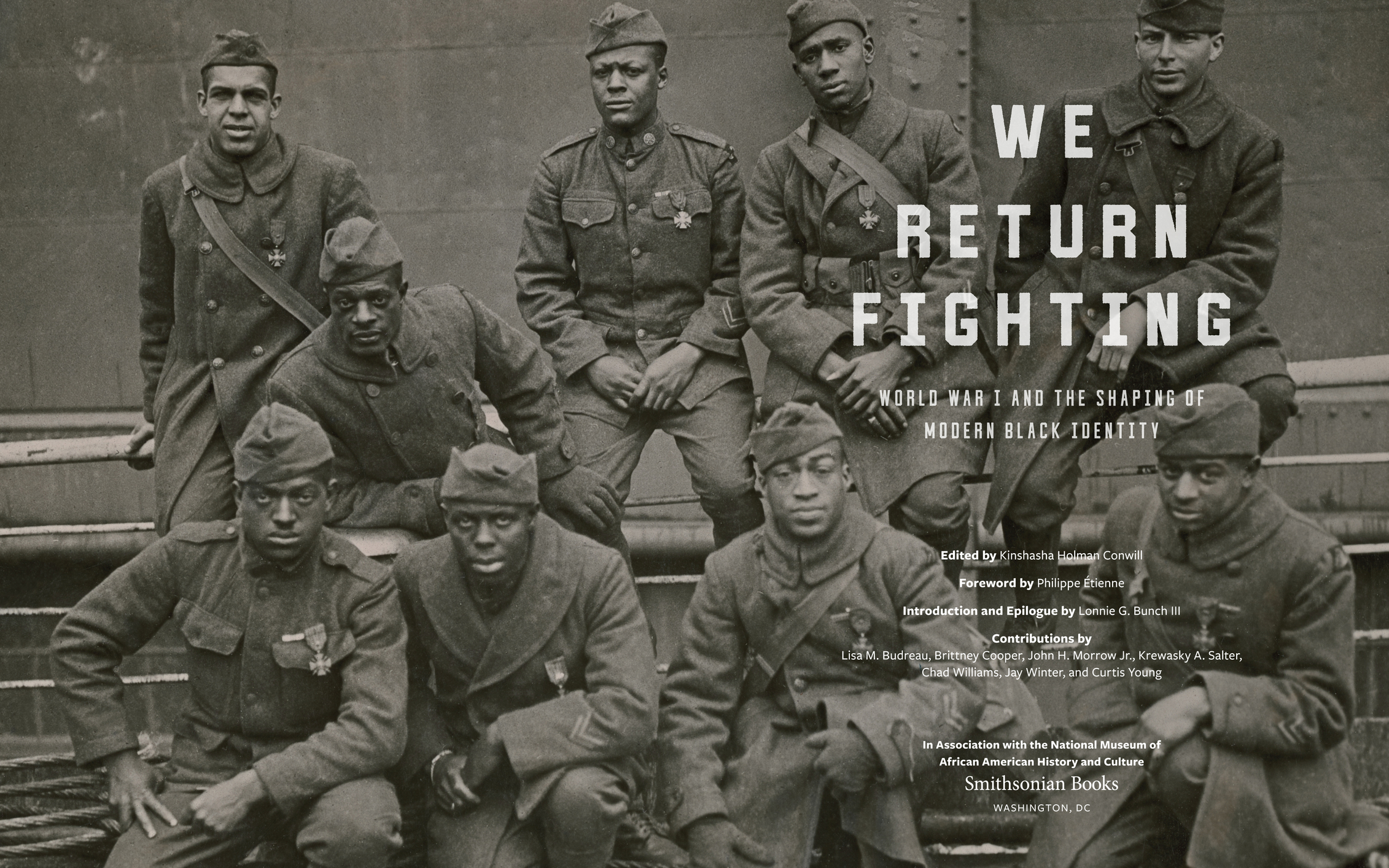

Soldiers of the 369th Infantry Regiment (Harlem Hellfighters) proudly wearing the Croix de Guerre they were awarded for gallantry in action on the battlefields of France, 1919.

Copyright 2019 Smithsonian Institution.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Advising Editor: John H. Morrow Jr.

Profiles and object profiles by Krewasky A. Salter and Douglas Remley

Timeline by William Pretzer and Arlisha Norwood

Captions by Krewasky A. Salter, Patri OGan, and Douglas Remley

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Creative Director: Jody Billert

Senior Editor: Christina Wiginton

Editorial Assistant: Jaime Schwender

Designed by Gary Tooth / Empire Design Studio

Edited by Erika Bky and Laura Harger

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Founding Director: Lonnie G. Bunch III

Deputy Director: Kinshasha Holman Conwill

Publications Team: Jaye Linnen and Douglas Remley

This book may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books,

PO Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as seen on . Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: National Museum of African American History and Culture (U.S.), author. | Conwill, Kinshasha, editor. | Bunch, Lonnie G., writer of introduction. | Morrow, John Howard, 1944- contributor. | Salter, Krewasky A., 1962- contributor.

Title: We return fighting : World War I and the shaping of modern Black identity / National Museum of African American History and Culture; edited by Kinshasha Holman Conwill; introduction by Lonnie G. Bunch III; contributions by John H. Morrow Jr. and Krewasky A. Salter.

Description: Washington, DC : Smithsonian Books, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: A richly illustrated commemoration of African Americans roles in World War I highlighting how the wartime experience reshaped their lives and their communities after they returned home Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019020417 (print) | LCCN 2019980989 (ebook) | ISBN 9781588346728 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781588346797 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 1914-1918Participation, African American. | World War, 1914-1918African Americans. | African American soldiersHistory20th century. | African AmericansHistory1877-1964. | World War, 1914-1918Influence. | African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. | African AmericansRace identity. | BlacksRace identityUnited States.

Classification: LCC D639.N4 N38 2019 (print) | LCC D639.N4 (ebook) | DDC 940.3/7308996073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019020417

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019980989

Ebook ISBN9781588346797

v5.4

a

Contents

Joseph-Flix Bouchor was embedded with the Allied forces as a war artist. This painting, Gassed French Infantryman Alerting African American Soldiers (1931), depicts a French soldier with African American soldiers of the 370th Infantry Regiment near Vauxaillon, France.

Foreword

One hundred years ago, France and the rest of the world were healing the wounds of a unique conflict of extraordinary dimensions. The exhibition We Return Fighting: The African American Experience in World War I, organized by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, concludes, in a remarkable way, the commemoration of the centennial of World War I by acknowledging and paying tribute to the role of African Americans during the war and in the years that followed. We remember the sacrifice of all those who crossed the Atlantic to serve in France, especially the brave soldiers from the four African American units of the 93rd Infantry Division, who fought under French command, with French equipment and arms. The critical involvement of these men in combat earned the members of the legendary 369th Infantry Regimentnicknamed the Harlem Hellfightersthe coveted French Croix de Guerre.

Beyond their valor during the war, the presence of these soldiers on French soil forever marked the French cultural landscape and started what can be described as a love story between Paris and the African American community, far from then-segregated America. African American soldiers in France brought with them elements of their own culture, and Paris became obsessed with jazz and black cultural heritage. During the interwar period, in particular, all emerging aspects of African American culture were welcomed and celebrated.

It is a great honor for the Embassy of France to be a partner of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, a museum that is distinguished by its ambition to undertake significant educational and cultural projects such as this one, and of course, by the quality of its collections. Organized with the support of Frances First World War Centennial Mission, this exhibition shows that the Great War was a moment of confrontation with the other, mixing races, nationalities, and cultures, profoundly changing the course of events and making this period unique in modern history.

Philippe tienne

Ambassador of France to the United States

A wounded soldier of the 369th Infantry (known as the Harlem Hellfighters) is welcomed home at the February 17, 1919, victory parade in New York.

Introduction

When I was a small child, my grandfather would read to me before bedtime. Among my favorite books was a pictorial history by Emmett Scott titled The American Negro in the World War, which entranced me with its photographs, including one of an African American soldier recently returned from battle at the European front. Marching along New Yorks Fifth Avenue in a homecoming parade in the winter of 1919, he has stopped to shake the hand of a woman in a long fur coat. At first I focused on the woman: with her wide smile and slight build, she looked just like my grandmother. Only later did I focus on the soldier himself: he is on crutches, and his right leg is missing below the thigh. Serving in the military, I realized then, was not only about valor and victory celebrations for returning warriors. It was also about sacrifice.