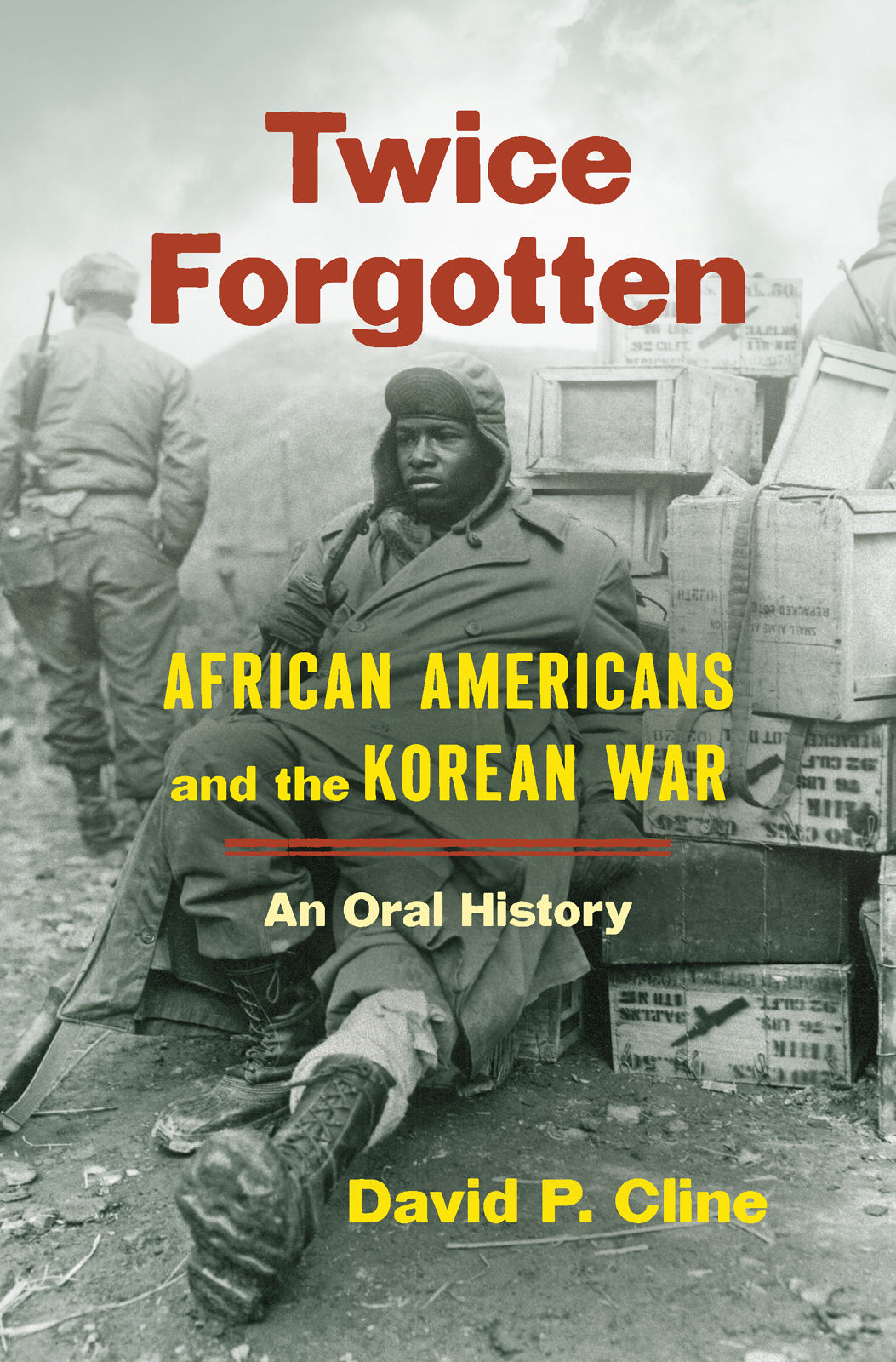

Twice Forgotten

AFRICAN AMERICANS and the KOREAN WAR

An Oral History

DAVID P. CLINE

The University of North Carolina Press

CHAPEL HILL

2021 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed by Jamison Cockerham

Set in Arno Pro, Scala Sans, Cassino, and Irby

by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Jacket photograph by Private 1st Class Charles Fabiszak, US Army, NARA File no. 111-SC-358355, Department of Defense HD-SN-99-03053

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Cline, David P., 1969 author.

Title: Twice forgotten : African Americans and the Korean War, an oral history / David P. Cline.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021030605 | ISBN 9781469664538 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469664545 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Korean War, 19501953Participation, African American. | Korean War, 19501953African American. | Korean War, 19501953Personal narratives, American. | African American veteransSocial conditions20th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / African American & Black | HISTORY / Military / Korean War | LCGFT: Oral histories. | Personal narratives.

Classification: LCC DS919 .C55 2021 | DDC 951.904/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021030605

A note on language: Throughout this book, the terms Black and African American are used interchangeably to describe Americans of African descent. Additionally, some narrators use words such as negro or colored that were in use during the time period they are discussing. The N-word, in its entirety, also appears a number of times in the interviews. In every instance, it is being used by an African American person quoting the hateful, demeaning, and terroristic language used against them by whites. While I understand encountering this word may be difficult for some readers, in order not to silence the narrators or blunt the intent and impact of the language they were subjected to, I have elected to reproduce the word without intervention.DPC

For

Larry Hogan, Ernie Shaw, Julius Becton, Charles Berry, and all those who answered the call.

Thank you for your inspiration.

Contents

A section of illustrations follows

Preface

The Fight of Their Lives

At the time that Charles Bussey was born in Bakersfield, California, in 1921, to be Black in America meant to be in a constant state of warfare. Growing up in a bigoted town taught me some hard lessons, he recalled, but it also taught him how to fight for himself. Perhaps more important, it also taught him the need to recover quickly before the next fight began, good training for leading troops into battle as commander of the segregated 77th Engineer Combat Company during the Korean War. Growing up as I did, helped prepare me for being a company commander in combat.

Although the history of the Black freedom struggle is as long as the history of African Americans in America, there are within it, as historian Adriane Lentz-Smith has put it in documenting the contributions of Black soldiers, certain moments [that] emerge as particularly formative or even transformative. She points to World War I as one of those moments, but the argument can fairly be extended to all US wars, African American participation in which created highly visible stepping-stones along a path to freedom. From the Revolutionary War forward, African Americans recognized military service and times of war as unique opportunities to both participate in citizenship and to apply pressure for a greater piece of the same. These wars, moments of national crisis and international vulnerability, emerge as fissures in the hard shell of the American racial order, times when African Americans were able to gain incrementally greater freedoms while exposing their ordeal on a global stage.

The desegregation of the military and the participation of African Americans leading up to and during the Korean War were key components of and building blocks for the long civil rights movement. By taking a moment to ride along on the shoulders of Black soldiers and sailors in the pages that follow, we shall see that the desegregation of the military took longer than most accounts have acknowledged. When desegregation finally arrived, it came as the result of a series of combined forces: the continuous and constant willingness of African Americans to take up the burden of armed service in a racially unjust military in order both to claim a piece of the American democratic promise and to force that democracy to include them at last; a sustained campaign of pressure from African American civil rights activists and organizations, from the Black press, and from ordinary citizens; the actions of President Harry S. Truman and the executive branch in pushing civil rights broadly, calling specifically for the desegregation of the military and directly pressuring the branches of the US Armed Forces; and the Korean War itself, the particular needs of which forced those branches that had lagged behind to scrap strict segregation.

African American participation in the armed forces, although its form differed within each war and historical period, served as a means to leverage new freedoms from a country that had long promised but failed to deliver them. At the same time, military service exposed African Americans to new ways of experiencing democracy, which in turn slowly led to increased demands for individual and collective access to that democracy. The pathbreaking service of the Tuskegee Airmen and other Black veterans of the world wars, for example, did not lead directly to Americas mass civil rights protests of midcentury nor to the civil rights legislation finally created in the 1960s, but it did bequeath a legacy of experience and tactics that would remain at the center of the movement as it came into full blossom.

In the stories that follow you will find painful segregation, pathbreaking but still sometimes painful desegregation, and childhood, family, training, war, and prisoner stories full of pathos and grit and sorrow and otherworldly forbearance. In other words, you will hear the voices of survivors. You may not hear the words civil rights mentioned oftenindeed, they were just joining the national lexicon during the years of the Korean Warbut make no mistake about it, this is a civil rights story. This is a story of people fighting to be recognized as people, as full human beings with all rights and privileges thereof and, not to put too fine a point on it, willing to sacrifice themselves to achieve it. Truman may have been a paternalistic integrationist and the armed forces under his command grudging and halting in their move toward equality, to say the least, and the bloody yawp of battles incessant need for more bodies the true reason that the races finally mixed, but it did happen. And it did make a difference that eventually led to greater change. Although the police action in Korea has at long last finally been officially acknowledged as the war that it was, its nickname, the Forgotten War, still remains sadly appropriate. But the men and women from twenty-two nations and from many backgrounds who served do not deserve that same fate. And especially those African Americans who served and who fought, not one war, but many, deserve to have their voices join the chorus of those who called for freedom. The African American veterans of the Korean War era do not deserve the fate of being twice forgotten.