2016 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Arno Pro by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cline, David P., 1969 author.

Title: From reconciliation to revolution : the Student Interracial Ministry, liberal Christianity, and the civil rights movement / David P. Cline.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016012007| ISBN 9781469630427 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469630434 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469630441 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Student Interracial Ministry. | African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. | Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | United StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. | Civil rightsReligious aspectsChristianityHistory20th century. | Race relationsReligious aspectsChristianityHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC E 185.61 .c627 2016 | DDC 323.1196/0730904dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016012007

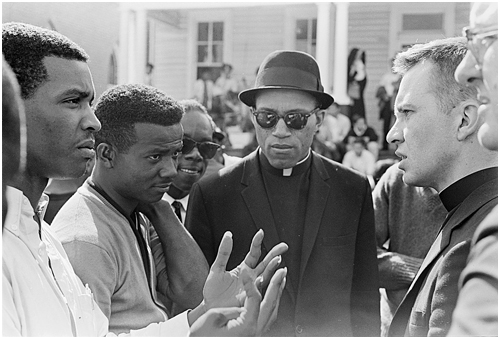

Cover illustration: Sneering priest among Selma protestors (Priest-Selma by John F. Phillips, 2016 Baldwin Street Gallery).

Preface

A Tale of Two Gatherings

It is only by living completely in this world that one learns to believe.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Just after Christmas 1955 in Athens, Ohio, an organization called the Student Volunteer Movement for Christian Missions hosted a gathering of over three thousand students, representing sixty religious groups from eighty countries. Roman Catholic, Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist groups attended, but the majority of students came from the mainline Protestant churches and collectively represented what was known as the Student Christian Movement (SCM). The title of the conference was Revolution and Reconciliation.

With its roots in the YMCA and YWCAs founded in the mid-1850s, the SCM was made up of those mainline Protestant campus ministries and organizations that were linked to one another and to their partners overseas through the World Student Christian Federation. It included within its ranks such venerable organizations as the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions, founded in 1886, and the Interseminary Movement, founded in 1880 to serve theological students. Each year, thousands of students, often from around the world, would gather for conferences comprising several days of discussion, fellowship, and prayer. Although discussions often concerned the power of religious young people to address social ills, they were rarely focused toward a specific set of goals.

Then came 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott, and the Revolution and Reconciliation conference. In the humble surroundings of Athens, Ohio, amid the thousands of students from across the globe, the Student Christian Movement embraced the civil rights movement. During the course of discussions, the global gathering explored American anticommunism from global vantage points, highlighting American economic and cultural imperialism. Panelists asked how Americans could force their democratic ideals on the rest of the world when they werent able to deliver on them themselves, and they charged the churches with leading a domestic change movement to bring about justice and equality at home.

A similar conference, also in Athens, was held the following year and continued the discussions, with topics ranging from radical expressions of faith to the birth of postcolonial nations overseas to the necessity of missionaries to focus more on justice and less on conversion. An editorial in the conference newspaper declared, Each of us must create for himself the bridge whereby his faith can lead to works. Out of the Athens conferences grew a seminal mission project of the Student Christian Movement: the Frontier Intern program, a Christian precursor to the federal Peace Corps. The conference ended on January 1, 1960. Exactly one month later, four students from North Carolina A&T sat-in to protest segregation at a Woolworths lunch counter in Greensboro, launching a wave of student sit-ins that swept through the South.

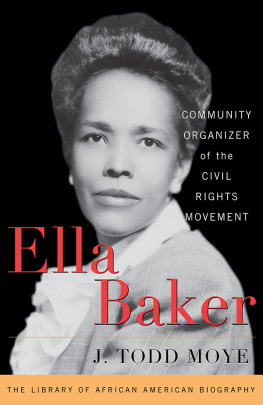

It was these sit-ins that inspired another important student gatheringthis one held at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, over Easter weekend 1960which brought together more than two hundred students representing some fifty-six colleges and high schools and thirteen activist and reform organizations. Called the Southwide Student Leadership Conference on Nonviolent Resistance to Segregation, it was organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) under the guidance of Martin Luther King Jr. and Ella Baker, SCLCs interim executive director, to discuss strategies for channeling the momentum generated by the sit-ins.

Ella Bakers invitation called on student leaders and supporters TO SHARE experience gained in recent protest demonstrations and TO HELP chart future goals for effective action.

The Union students who headed to North Carolina that Easter weekend also represented a trend among students involved in the Student Christian Movement; by 1960, many Christian students had already jumped to the other side of a generation gap forming between them and older ecumenical leaders. In the case of seminarians, that older generation included most of their theology professors, and students were running out of patience with the status quo. It was a bust, recalled one prominent member of the older generation. Students wanted to be inspired, but they were not interested in the wisdom their elders had gained from fighting other battles in other decades. These students now had their own battle and were already imagining themselves as a potentially important cadre within the foot soldiers of the growing civil rights movement.

Ella Baker, who had grown up in the South but had cut her teeth in organizing in New York City and through a long association with the NAACP, was within a month of leaving the SCLC, to be replaced by Wyatt Tee Walker as director. She had chafed under the ministers leadership, which she found imperious and often dictatorial, and was ready for both a change of scene and a change of leadership style. She relished the enthusiasm of the students, and especially the egalitarian, communitarian impulses of Reverend James Lawson and his student group from Nashville, which was rooted in a commitment to nonviolent protest and a belief in the so-called beloved community. As the conference unfolded, Baker remained behind the scenes, convinced that the movement sparked by student initiative should continue to be student led.

During his opening remarks, Lawson claimed that students had long harbored strong beliefs about equality and justice but had been simply waiting in suspension; waiting for that cause, that ideal, that event, that actualizing of their faith which would catapult their right to speak powerfully to their nation and world.