Copyright 2013 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern

Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky

Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray

State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University

of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

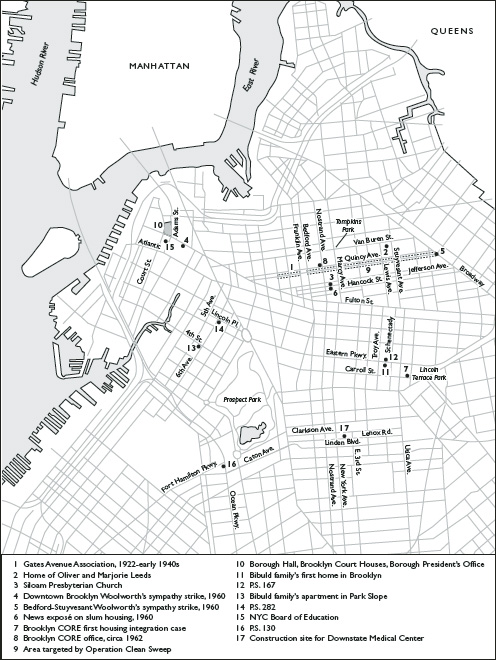

Photographs Bob Adelman. Maps by Bill Nelson.

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Purnell, Brian, 1978-

Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings : the Congress of Racial Equality in

Brooklyn / Brian Purnell.

pages cm. (Civil rights and the struggle for black equality in the twentieth

century)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-4182-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4183-1 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8131-4184-8

1. Brooklyn (New York, N.Y.)Race relationsHistory20th century.

2. Congress of Racial Equality. Brooklyn Chapter. 3. African AmericansCivil

rightsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. 4. Civil rights

movementsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. 5. New York

(N.Y.)Race relationsHistory20th century. I. Title.

F129.B7P87 2013

323.11960730747dc23

2013001707

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American

National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of

American University Presses

N OSTALGIA , N ARRATIVE, AND N ORTHERN C IVIL R IGHTS M OVEMENT H ISTORY

What was that place called Brooklyn really like back then, when you were growing up?

Elliot Willensky, When Brooklyn Was the World,

19201957

Only two things have remained constant in the history of race in Brooklyn: the social symbolism of color and the extraordinary maldistribution of power. The former has faithfully followed the career of the latter.

Craig Steven Wilder, A Covenant with Color:

Race and Social Power in Brooklyn

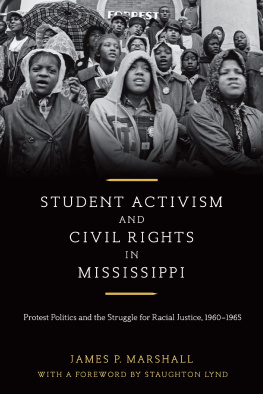

On February 3, 1964, one of the largest civil rights demonstrations in U.S. history occurred. Nearly half a million students boycotted a racially segregated municipal public school system as parents and activists demanded a plan for comprehensive desegregation. Ten years after the Supreme Courts Brown v. Board of Education decision had declared racially segregated public schools unconstitutional, this citys government had failed to desegregate the school system. The integration movement rallied behind a Christian minister, a man known for his eloquent, trenchant sermons against racial discrimination and poverty. He transformed his church into a movement headquarters, which organized racially integrated freedom schools throughout the city. The man and the movement made history.

But this ministers name was Milton, not Martin; and his church was in Brooklyn, New York, not Birmingham, Alabama.

Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings narrates the history of the early 1960s civil rights movement in Brooklyn, New York, through an analysis of the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). This book highlights the ways northern civil rights activists worked diligently for roughly five years to make forms of racial discrimination in New York City visible to the public and matters of political debate. The chapters that follow also examine how Brooklyn CORE developed a culture of interracial camaraderie through creative direct-action protest campaigns, and how it formed alliances with numerous community-based organizations and local civil rights activists, such as the Reverend Milton Galamison, referred to above. The demonstrations that clearly dramatized the everyday ways racial discrimination circumscribed black citizens social lives and economic opportunities won Brooklyn CORE a seat at negotiation tables, and in some cases the chapter secured jobs, housing, and improved city services for black Brooklynites. Mostly, though, an assortment of power brokersunion leaders, elected officials, real estate tycoons, business managers, and school board officialsignored Brooklyn COREs protests, made limited concessions on certain demands, or used investigations and empty promises to delay dealing with widespread forms of racial discrimination. This book therefore pays close attention to Brooklyn COREs shortcomings and failures. Its narrative invites readers to question how any band of activists could eliminate systematic forms of racial discrimination, especially without strong, clear, consistent government support, at both the local and national levels.

Most readers will come to this book familiar with what the civil rights movement veteran Julian Bond calls the master narrative of the movement. This version of the civil rights movements history covers the mid-1950s through mid-1960s, when national leaders and nonviolent activists eradicated Jim Crow policies in the South. The movement achieved major legislative victories in the form of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts and moved the country closer to true democracy, but it declined when activists brought nonviolent protest tactics north. There the civil rights movement encountered riotous African Americans, black power activists, and white backlash. This master narrative is essentially built on a series of dichotomies: North versus South; racial integration versus black power; nonviolent pacifism versus self-defense and violence; the good early 1960s versus the bad late 1960s. Like many heroic histories, the civil rights movements master narrative and its accompanying dichotomies overlook a far more complex, wide-ranging story. They limit civil rights movement history to roughly one decade of

Academic historians have developed three frameworks that challenge this master narratives interpretations. The freedom North paradigm expands the geographic scope of the civil rights movement. These studies show that activists fought against local forms of racial discrimination outside the South before, during, and after civil rights movements emerged in southern cities and towns. Northern, urban activists created struggles for black economic and social justice that demanded employment opportunities, desegregated education systems, open housing, and increased political power. This scholarship has proven that the movement did not move from the South to the North; it was already there, and in some places it predated the more familiar southern movement. The history of the civil rights movement outside the South also shows that the national struggle against racism did not end when states or Congress passed antidiscrimination laws and enshrined voting equality; nor did northern civil rights movements fall apart because black power movements emerged. Black power, in many cities outside the South, represented continuations of earlier civil rights movement struggles, albeit with different philosophies, organizations, leaders, and strategies.