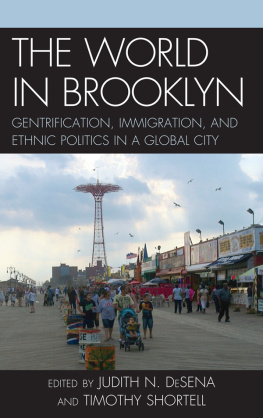

Edited by Judith N. DeSena and Timothy Shortell

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

ISBN: 978-0-7391-6670-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

Introduction

The World in Brooklyn

Judith N. DeSena and Timothy Shortell

T hroughout its history, Brooklyn has been a destination for many. Brooklyn is ranked the 4th largest city in America and a major contributor to New York Citys first place ranking. With its Native American roots and pastoral beginnings, to Dutch migrants engaging in commerce and building the environment, and European descendents opening factories to immigrants seeking work, Brooklyn accommodated one and all. Its role in this regard continues. While there has been a shift to a service economy and a change of immigrant and migrant groups, the amenities that Brooklyn offers have kept pace. Brooklyn is a mosaic of diversity comprised of always changing neighborhoods. Brooklyn adjusts and is recycled to meet social needs.

Like other global cities, the story of contemporary Brooklyn is about, in large measure, mobility. As Abrahamson (2004) noted, until quite recently, most of the movement of people and goods occurred within national boundaries rather than between them. In this age of globalization, the ratio has shifted toward global mobility. The number of immigrants to New York City in the 1990s was nearly twice the number from the 1980s (New York City Department of City Planning 2004). In 2009, there were more than 900,000 foreign-born persons in Brooklynmore than the entire population of any city in Florida, and roughly the size of San Jose, California, the tenth largest city in the U.S. (U.S. Census 2011).

But the global movement of people did not erase or negate other kinds of mobility in Brooklyn. The displacement of lower status communities by higher status populationsalso known as gentrificationcontinues to accelerate. Migration, domestic and global, intersects with social class mobility, of course, and takes place in the context of our long history of race relations. Brooklyn is a place of neighborhoods, and these communities get ascribed with social identities just as people do. So the story of contemporary Brooklyn is a story of immigrant neighborhoods and native-born neighborhoods, of black neighborhoods and white neighborhoods, of poor neighborhoods and rich ones.

Brooklyns image and reputation has been transformed. Popular representations include iconic places like the Brooklyn Bridge, Coney Island, and Juniors Restaurant with its gritty waterfront and rough neighborhoods inhabited by residents who speak with a vernacular Brooklyn accent. Present day Brooklyn has a different picture. Reflections are of Brownstone Brooklyn, hip Williamsburg, and enduring poverty in neighborhoods like East New York. For many newcomers, it is with pride that one resides in Brooklyn. But there is no one Brooklyn. Residents have distinct experiences in that Brooklyns neighborhoods can provide them with dissimilar worlds. What has been constant about Brooklyn is that it has, throughout its development, embraced the world. Thus, we arrive at this book.

The World in Brooklyn: Gentrification, Immigration, and Ethnic Politics in a Global City , is a collection of scholarly papers which analyze demographic, social, political, and economic trends that are occurring in Brooklyn. Brooklyn, as the context, reflects global forces while also contributing to them. The idea for this volume developed as the editors discovered that there is a group of scholars from different disciplines and various universities studying Brooklyn. Brooklyn has always been legendary and has more recently regained its stature as a much sought after place to live, work, and have fun. Popular folklore has it that most U.S. residents trace their family origins to Brooklyn. It is presently referred to as one of the hippest places in New York. Thus, we think a collection of demographic, ethnographic, and comparative studies which focus on urban dynamics in Brooklyn is timely.

This book investigates issues of social class, urban development, immigration, race, ethnicity, and politics within the context of Brooklyn. It begins with a demographic profile of Brooklyn. In Mapping a Changing Brooklyn, Mapping a Changing World: Gentrification and Immigration, 20002008, Lorna Mason, Ed Morlock, and Christina Pisano use Census microdata to uncover four distinct spatial patterns. Northwest Brooklyn, often called gold coast Brooklyn is experiencing gentrification by U.S. migrants who are highly educated and mostly white. The outer circle of Brooklyn is composed largely of new and existing immigrant populations. New residents are mostly foreign born, lower income, and ethnically mixed relative to the existing population. Between the gold coast and the outer circle are newcomers who are predominantly white and lower income, and are bringing change to black and Hispanic immigrant neighborhoods. Finally, the most eastern portion of Brooklyn shows little change.

The next chapter, Forgetting Poverty in Brooklyn and the United States, William DiFazio carries out an analysis of one of the neighborhoods in Brooklyn that has not changed much, but presents persistent poverty. He examines poverty through the guests of a soup kitchen in Bedford-Stuyvesant. He shows that poverty in Brooklyn is a reflection of poverty in the larger United States, and that it has become a problem of the middle class as well. According to DiFazio, the global economic crises have worsened conditions for the poor in Brooklyn.

The following section of chapters focus on gentrification and development and in some cases indicates how development is used as an engine of gentrification. Judith N. DeSena discusses Gentrification in Everyday Life in Brooklyn. With a spotlight on Greenpoint, this chapter analyzes neighborhood change viewing social class as an element of the local culture. It points out how social class differences lead to the creation and maintenance of parallel cultures. This theme is illustrated by exploring the everyday struggles between gentry and working class residents, and the choices made to separate according to social class rather than assimilate and integrate.

Sara Martucci examines an annual event in her chapter on Williamsburg Walks: Public Space and Community Events in a Gentrified Neighborhood. Through a community event, this article indicates another way that gentrification creates social segregation, and exemplifies DeSenas notion of parallel cultures. Exclusionary practices were used in this event, according to Martucci, to create a new brand for a neighborhood.

Kenneth Gould and Tammy Lewis explore The Environmental Injustice of Green Gentrification: The Case of Brooklyns Prospect Park. This chapter reveals how the revitalization of an environmental amenity, in this case Prospect Park, contributes to the displacement of poor and minority residents living in surrounding neighborhoods. The rejuvenation of environmental amenities, according to Gould and Lewis, raises property values which results in pricing-out long-term residents. For Gould and Lewis, this process might be especially discouraging for environmental justice activists to find that success harms the very population they work to protect.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.