This Light of Ours

This Light of Ours

Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement

Edited by Leslie G. Kelen

Essays by Julian Bond, Clayborne Carson, and Matt Herron

Text by Charles E. Cobb, Jr.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Photograph on pages 1 and 2: Matt Herron, Alabama, 1965

Copyright 2011 by Center for Documentary

Expression & Art

Photographing Civil Rights copyright 2011

by Matt Herron

How I First Saw King and Found the Movement copyright

2011 by Clayborne Carson

Photographs 2011 Matt Herron/Take Stock

Photographs 2011 George Ballis/Take Stock

Photographs 2011 Bob Fitch/Take Stock

Photographs 2011 Maria Varela/Take Stock

Photographs 2011 Tamio Wakayama/Take Stock

Photographs 2011 Bob Fletcher

Photographs 2011 Herbert Randall

Photographs 2011 Bob Adelman from Mine Eyes Have Seen

Photographs 2011 David Prince/Take Stock

All rights reserved

Manufactured in China

First printing 2011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

This light of ours : activist photographers of the civil rights movement / edited by Leslie G. Kelen; essays by Julian Bond, Clayborne Carson, and Matt Herron; text by Charles E. Cobb, Jr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61703-171-7 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-61703-172-4 (ebook) 1. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th centuryPictorial works. 2. Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th centuryPictorial works. 3. United StatesRace relationsHistory20th centuryPictorial works. 4. Southern StatesRace relationsHistory20th centuryPictorial works. 5. PhotographersPolitical activityUnited StatesHistory20th century. 6. Political activistsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 7. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (U.S.)History. 8. PhotographersUnited StatesInterviews. 9. Political activistsUnited StatesInterviews. I. Kelen, Leslie G., 1949 II. Bond, Julian, 1940 III. Carson, Clayborne, 1944 IV. Herron, Matt, 1931 V. Cobb, Charles E., Jr.

E185.615.T495 2011

305.800973dc23

2011016247

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

DEDICATION

Publication of this book was supported generously by the Board of Directors of the George S. and Dolores Dor Eccles Foundation, in honor and memory of fellow board member Alonzo W. Lon Watson, Jr. (19222005) whose service for more than 25 years was highlighted by his dedication to building a more just and compassionate society.

Board of Directors

Spencer F. Eccles, Chairman & CEO

Lisa Eccles, President

Robert M. Graham, Secretary, Treasurer & General Counsel

Contents

Text by Charles E. Cobb, Jr.

This little light of mine

Im going to let it shine

Oh, this little light of mine

Im going to let it shine

Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.

Movement anthem and African American gospel song, written by Harry Dixon Loes

Preface and Acknowledgments

Leslie G. Kelen

Anyone who has worked long on a book project knows that a preface is written after a project is completed as a way of providing a synopsis of the effort and an introduction to the reader. The preface to This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement isnt an exception. Nevertheless, in preparing to write it, I found myself reluctant to admit the project is over. In large part, this is because the project has been enormously transformative. It has provided all of us at the Center for Documentary Expression & Art (CDEA) who worked on it with a new appreciation for the complexity of the Civil Rights Movement and a deeper understanding and regard for the thousands of people (young and older, known and relatively unknown) who carried out its actions.

Personally, I feel fortunate to have been able to form a relationship with the photographers whose work is in this book and to have the honor to participate, in some small way, in telling their stories. The Civil Rights or Southern Freedom Movement is unquestionably one of the shining moments in the history of this nation. It wasand remainsone of the moments when people (as photographer Matt Herron and others observed) moved beyond their usual capacities and risked their safeties and, in some cases, their lives to realize the civil and human rights of African Americans and, by implication and example, other disenfranchised American people. And as the photographs and accompanying text in this book demonstrate, the movements achievements continue to reverberate throughout our communities as good tidings and as powerful reminders of our capacity to stand up against the evils of racism. So, reader, please consider this preface as both a reluctant admission of work completed and as invitation to you to experience it and to use its lessons to enrich your life and the lives of others. As SNCC communications director Julian Bond writes in the foreword that follows: The photographs you see here remind us of what we wereand what we hope we can be again.

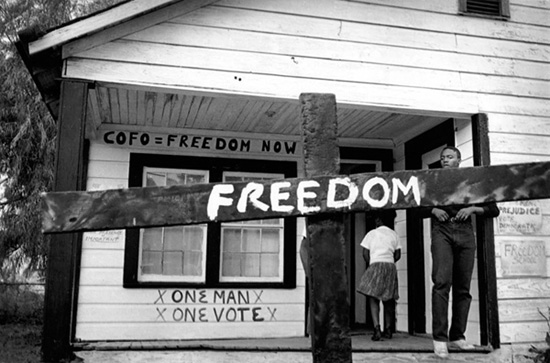

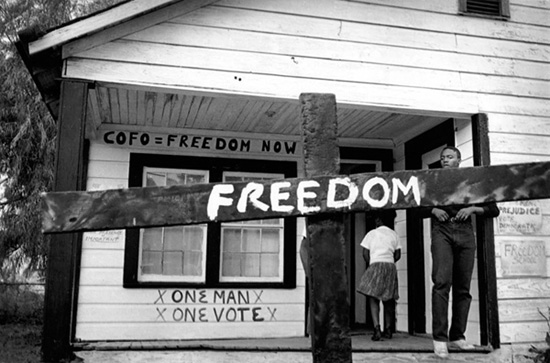

This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement presents the work of nine men and women who lived and worked in the American Civil Rights Movement between 1963 and 1968. (The book is also the catalogue to a major traveling exhibition of the same title.) As a group, the photographers represent two generations of Americans from an array of ethnic identities (i.e., African American, Greek, Irish, Japanese, Jewish, Mexican, and WASP) as well as people from both coasts and the veritable heartland. Unlike the photojournalists who entered the movement on assignment for magazines and newspapers and left after completing their work, each of these photographers chose to live in and participate in the movement as an activist. Herb Randall, David Prince, and George Ballis stayed directly engaged in the movement for several months. Bob Adelman, Bob Fitch, Bob Fletcher, Matt Herron, Maria Varela, and Tamio Wakayama stayed in the movement anywhere from a year to five years. Three of the nineFletcher, Varela, and Wakayamabecame photographers as a result of the movement. The other six came to the movement with varying degrees of training and experience. The majority of these photographers did not then and do not now see themselves primarily as photographers but as activists or organizers with cameras. And this self-definition is important to keep in mind when considering this book and what it represents; each of these people participated in the Southern Freedom Movement because it was what their lives, their deepest instincts, called for. And as the interviews and biographies suggest, their activismwith and without camerascontinued long after their participation in the movement ended.

Seven of the nine photographers were either staff members or close associates of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCCpronounced snick). The other two worked for or were engaged with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Of the major civil rights organizations, SNCC was, it turns out, uniquely farsighted in its usage of photographers and photographs. Soon after its 1960 founding in Raleigh, North Carolina, this student-led organization invited photographers to be an integral part of their communications effort. And by the summer of 1964, when the bulk of the photographers in this book arrived on the scene, SNCC had a working darkroom in Atlanta and was fielding a team of photographers to document the organizations activities and to use photos to convey the aims and struggles of the movement to the nation.

Next page