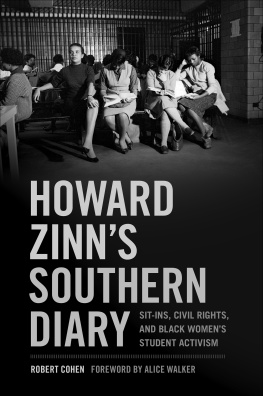

Howard Zinns Southern Diary

Howard Zinns Southern Diary

Sit-ins, Civil Rights, and Black Womens Student Activism

ROBERT COHEN

Foreword by ALICE WALKER

This publication received generous support from the Stephen M. Silberstein Foundation.

Poem My Teacher Alice Walker, excerpted with permission of Alice Walker.

2018 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

Foreword 2018 by Alice Walker

Spelman Diary 1963 the Howard Zinn Revocable Trust

All rights reserved

Designed by Melissa Bugbee Buchanan

Set in Minion Pro and Myriad Pro

Printed and bound by

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 P 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zinn, Howard, 19222010, author. | Cohen, Robert, 1955 May 21editor, writer of added commentary. | Walker, Alice, 1944writer of foreword.

Title: Howard Zinns Southern diary : sit-ins, civil rights, and black womens student activism / Robert Cohen ; foreword by Alice Walker.

Description: Athens : The University of Georgia Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017059453| ISBN 9780820353227 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780820353289 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780820353234 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Zinn, Howard, 19222010Diaries. | Spelman CollegeHistory. | Southern StatesRace relationsHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC PS3576.I538 Z46 2018 | DDC 818/.5403 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017059453

In memory of Marilyn Young (19372017), whose brilliant historical scholarship challenges us to confront Americas addiction to war.

And to Spelman College activists, past and present, in their courageous struggle for a more just and democratic world.

CONTENTS

by Alice Walker

FOREWORD

What Nurtured My Outrage, Really?

Alice Walker

When Spelman Colleges president, Albert Manley, fired Howard Zinn, my favorite teacher, it never occurred to me not to react. I was completing my sophomore year and had studied one semester with Zinn, yet it was obvious to me that he was a great teacher and an extraordinary person. He was fired at the beginning of summer, as his family prepared to transition to New England for the season. This was rude and awkward timing that caused unnecessary suffering after such an unexpected blow. I thought this manner of ejecting a controversial teacher extremely cowardly and could not bear to seem to condone or accept it.

I wrote a letter of protest that was published in our student newspaper, a letter that led inevitably to my own exit from a school that I struggled with, but deeply loved.

But what nurtured my outrage, really? I have been contemplating this question since Robert Cohen, the author of this book, asked me to write a foreword for it. And I must say, I have uncovered many beautiful reasons why I knew instinctively that I must stand up for Howard Zinn, my slim teacher, as I sometimes thought of him. But these beautiful reasons Zinn never knew about, because the world we live in is so fragmented that our family histories are rarely depicted in ways that show how they influence each other, connect, or intertwine.

I stood up for Howard Zinn, a Jewish teacher of History, a husband and father in his forties, because I in fact come from a community that venerates teachers.

Reaching this understanding only recently brought tears, as I allowed my deep appreciation for my southern black, farming, and sharecropping community to blossom once again in memory. In fact, memory encompasses years before I was born, when my father, riding a mule, went off in search of teachers for the school the vibrant but struggling community built, against nearly impossible odds, for its young.

a black descendant of white Reynolds Plantation folks. Never to have children of her own, she gifted my mother with my very first clothing. She married one of our cousins, also a descendant of a local white landowner. (This explains how he kept his land when other black farmers, after Reconstruction, were dispossessed.) This cousin provided the land for the school, and Miss Reynolds offered the love and guidance that kept it going. An earlier school, whose ruins remained visible for years in our churchs cemetery, had been burned to the ground by local whites. I mention the mixed ancestry of this couple to place them squarely at the heart of this poor community. There was a sister of the landowner cousin who behaved as though she were white, but we noticed, as she taught us grudgingly and with high yellow condescension, that she consumed a lot of prunes.

It is sometimes thought that in small isolated communities such as ours it is the preacher who is most cherished. It is true that on his monthly or bimonthly visits his was the honored seat at our pine board table. His was the plate with the most butter beans, greens, Irish potatoes, yams. Certainly the biggest and most crisp piece of fried chicken. His word was virtually law, as he hemmed and hawed his way through biblical stories he entertained us with in church. Sometimes he made very little sense because we knew none of the folks he talked about, all white, and very hairy, from a land that existed not only geographically and mythically far, but also may not have existed at all. It was a puzzle that was never solved, just who these people were, or how they ended up in our church. Besides, and lucky for us, we had our own animal folktales about animals we actually knew and saw sometimes (in the case of rabbits) several times a day. Church was always saved by song. Passion. Compassion. The genius of soul expressed in melodies whose high notes could curl your toes. There was laying on of hands and washing of feet. Folks fainting. Women in white from head to toe fanning anybody who looked queasy.

But it was the teacher who was truly cherished. Though I sense, from the distance of many decades, that the folks had to be careful to hide how much adoration they gave to those who taught their children, and sometimes themselves, how to read and write.

Without our teachers we were destined to sharecrop, to be maids and butlers, forever. Grownups got that, though many children did not. I was lucky that books held a revered place in our rustic shack, which my mother managed to make appealing through a genius for creating beauty that left her family in awe. And we were storytellers. If stories were hidden in books, as we discovered they were, it was our job to bring them out. We could only manage that by reading them.

Magic.

And so, with this history of my parents feeding teachers, my grandparents providing housing for them in the form of a spare room in their small house, my mothers sending of cakes and pies, on a monthly basis, to whomever was teaching her children, my father and grandfather cutting cords of wood to keep whatever teacher theyd enticed to our community warm for a winter, I understood that teachers are never to be treated shabbily.

That wherever a teacher is treated badly is no place for a person from my family or from my community.

I did not know what I would do after writing my anguished letter about the cruel treatment of Howard Zinn (and his family); I didnt even consider this. Nor did I have any clue how I, a scholarship student, could continue my education if Spelman threw me out. All I knew was that where I came from people stood with their teacher, if that teacher was respected and loved.

Next page