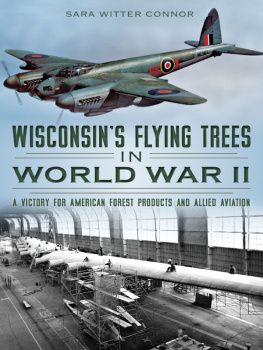

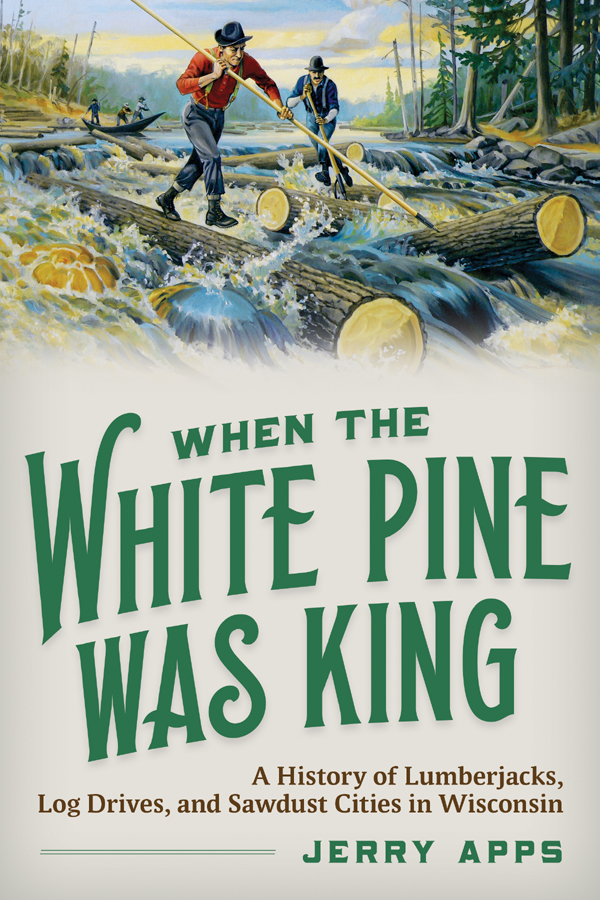

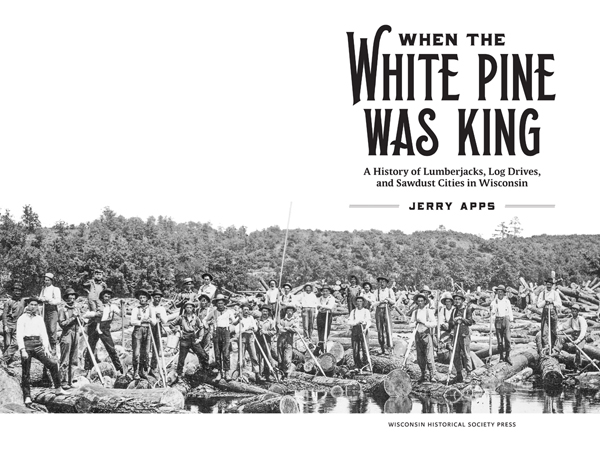

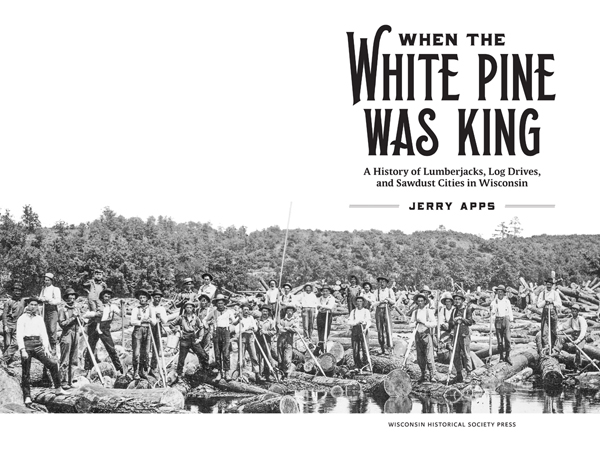

When the White Pine Was King

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories. Founded in 1846, the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions.

Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership

2020 by Jerold W. Apps

E-book edition 2020

Publication of this book was made possible in part by a grant from the Alice E. Smith fellowship fund.

For permission to reuse material from When the White Pine Was King: A History of Lumberjacks, Log Drives, and Sawdust Cities in Wisconsin (ISBN 978-0-87020-934-5; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-935-2), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Front cover image: John Boettcher, used with permission

Pages iiiii image: A log-driving crew for the Chippewa Lumber and Boom Company breaks up a jam, 1895; WHi Image ID 1895

Designed by Percolator Graphic Design

24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Apps, Jerold W., 1934 author.

Title: When the white pine was king : a history of lumberjacks, log drives, and sawdust cities in Wisconsin / Jerry Apps.

Description: Madison, WI : Wisconsin Historical Society Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020001652 (print) | LCCN 2020001653 (ebook) | ISBN 9780870209345 (paperback) | ISBN 9780870209352 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: LoggingWisconsin. | LoggersWisconsin.

Classification: LCC HD9757.W5 A67 2020 (print) | LCC HD9757.W5 (ebook) | DDC 338.1/749809775dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020001652

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020001653

CONTENTS

I grew up in central Wisconsin hearing lumberjack tales. My Grandfather Apps had been a cook in a lumber camp long before my time, and my family passed along some of his stories. We had twenty acres of woodlot on our farm, mostly oaks, but no giant white pines like the ones I heard had once covered the northern regions of the state. I was fascinated, and I wanted to learn more.

I was introduced to axes and crosscut sawsthe lumberjacks essential toolsas I helped my dad cut firewood for the woodstoves that heated our drafty farmhouse in winter. We spent considerable time every fall making wood: cutting down dead oaks with axes and two-man crosscut saws, then dragging the logs with our team of horses to the farmstead, where we piled them to await the sawing bee.

On a late-autumn Saturday, Pa would invite neighbors to stop by for a few hours of wood sawing. A half dozen or so men would come by. Guy York brought his circle saw, powered by an old Buick engine and designed primarily for slicing oak logs into blocks that would later be split. The big saw screamed as York fed it each hunk of oak wood; it spewed out a ribbon of sawdust that gathered at his feet. Four other men, usually working in teams of two, carried logs and limbs to the saw. Another man tossed the cut pieces onto an ever-larger pile. When the pile was deemed large enough, York and the crew moved the saw a few feet farther away. Sawing continued, and another wood pile was built. (In the language of the day, each pile of cut wood was referred to as a set, referring to how many times the saw had been set up, moved, and set up again. When someone asked the size of his woodpileas folks in our neighborhood were apt to doa farmer might reply four sets or five sets.)

We also occasionally cut oak trees for lumber to be used on the farm. We hauled the oak logs to a sawmill in Wild Rose owned and operated by Ernest Knoke. He sawed the logs into two-inch planks that we made into a stone boat to use for removing stones from our rocky farm fields. During World War II, Knokes sawmill became one of Wild Roses major employers. I enjoyed visiting the sawmill and hearing the scream of the enormous circle saw as it sliced its way through oak logs. The sawyer rode on a carriage that moved the log against the saw, and when the saw reached the end of the log, the carriage shot back on its rails before making another cut. It was a loud but fantastic event. During the 1940s and 1950s, Knoke bought marketable timber, mostly oak, from nearby farms. He would send a crew of men with axes and chainsaws and logging trucks to the farms where the logs were cut. They hauled the logs to his mill to be cut into railroad ties, which were in high demand, especially during the war years.

Ive always enjoyed stories and images of lumberjacks, like this one taken by photographer Charles Van Schaick of Black River Falls over a hundred years ago. WHI IMAGE ID 92880

When Waushara County organized a 4-H club in our community, I signed up for the clubs forestry project. I received a little booklet that included descriptions of the various species of trees that grow in Wisconsin, from the giant oaks I was familiar with in our woodlot to the aspen trees that Pa called popple. I learned how to identify trees by inspecting their leaves and needle clusters and to recognize them in all seasons of the year, even in winter, when hardwoods have no leaves.

As a 4-H forestry project member, I received, at no charge, fifty tiny pine seedlings that I planted in a transplant bed. I grew them there for a couple of years and then replanted them on the north side of our woodlot. Today those trees stand seventy-five feet tall and taller. I proudly show them to my grandchildren when we drive by.

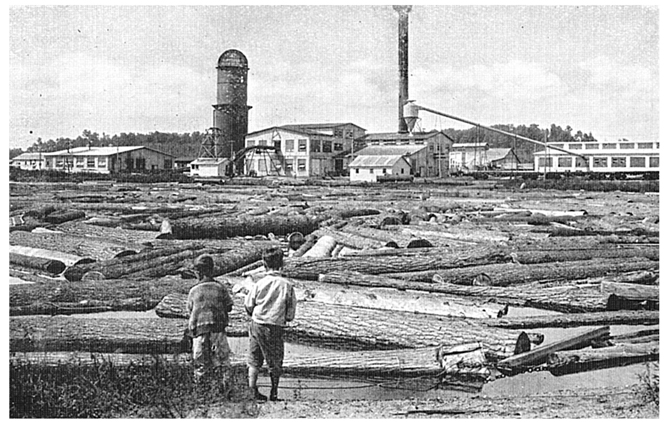

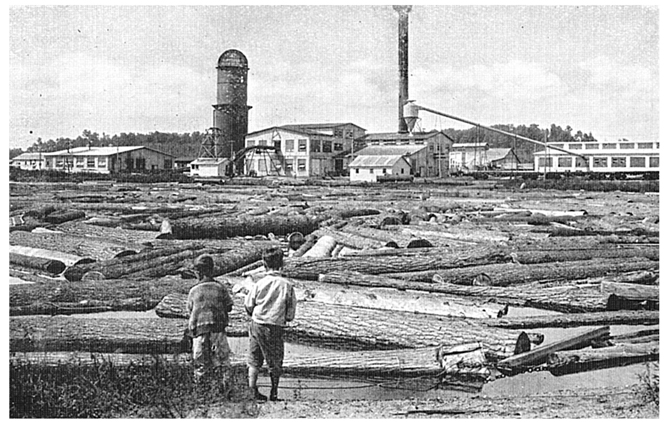

One summer in the late 1940s, our forestry group members visited a working logging camp on the Menominee Indian reservation. We talked with the lumberjacks, ate lunch with them in their cook shanty, and visited the sawmill at Neopit. I found the logging and sawmill operation impressive, and I was captivated by the magnificent white pines that grew on the reservation. The reservation land had been spared from the clear-cutting of nearly all white pine across the rest of northern Wisconsin, and the Menominee were following sustainable forestry practices, meaning that they selectively cut trees and replanted for future harvests.

A postcard view of the Menominee Indian Reservations sawmill at Neopit. WHI IMAGE ID 84544

My fascination with trees and forests continued into adulthood. Since 1966, my family has established a tree farm on our land in Waushara County. We have planted at least fifty pine trees every year that we have owned the place; one year we planted seventy-five hundred trees (with the help of a mechanical tree planter). Five years ago, I purchased sixty additional acres of mostly hardwood forest adjacent to our farm, and today we have about one hundred acres of trees, half of them white and red pine and half hardwoods: white oak, black oak, bur oak, maple, birch, black cherry, and poplar. With the help of the Wisconsin Forest Management Program and a professional forester, we practice selective thinning and logging with the hope that my grandchildren and their grandchildren will be able to enjoy our Roshara for years to come.